V&A Online Journal

Issue No. 7 Summer 2015

ISSN 2043-667X

An Unusual Embroidery of Mary Magdalene

Roisin Inglesby

Curator of Architectural Drawings, Historic Royal Palaces

Abstract

The recent discovery of an anonymous 17th-century embroidered picture of Mary Magdalene raises questions about the use of domestic embroidery in the early modern home. Iconographically unique, the embroidery does not fit within established historiographical understandings of the nature and uses of women’s needlework. By focusing on the visual qualities of the ‘embroidery-as-object’ rather than the rhetoric surrounding ‘embroidery-as-activity’, this article addresses the possibility that this piece could have functioned as a devotional rather than simply decorative object.

Introduction

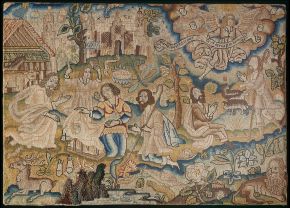

Figure 1. Mary Magdalene Surrounded by Instruments of the Passion

In 2006 conservators at the V&A found a miscellaneous object during a routine audit of the furniture conservation studios. The object, which bore no museum number or associated information, is a small embroidered picture showing Mary Magdalene reclining in a garden alongside traditional iconography of the Crucifixion. The central scene is framed by a border depicting the instruments of the Passion (fig. 1).

Immediately recognisable as a piece of English 17th-century domestic needlework, the embroidery was attached to a later piece of silk that bears signs that it was once nailed to a board or frame. It seems likely that at one time the object had been taken to the conservation studio for release from this frame and was never reclaimed; an unremarkable footnote in the institutional afterlife of what the Museum terms an ‘orphan’ object. Further investigation has ultimately shown that the embroidery was part of a collection of objects donated to the Museum by a Mrs Alec Tweedie, a remarkable travel writer and women’s rights campaigner who surely deserves an article in her own right.(1) Mrs Tweedie’s publications document travels as wide as A Girl’s Ride in Iceland (1889), and Mexico As I Saw It (1901), and subjects as broad as Danish versus English Butter-Making (1895) and Cremation the World Around (1932). Evidently her collecting habits reflected this somewhat eccentric diversity; a note in the V&A’s acquisition file remarks that her collection consists of ‘mostly chance scraps picked up without any plan during her travels’.(2) However, as suggested by her 1916 memoir, My Table-cloths; A Few Reminiscences, Mrs Tweedie was also a keen embroiderer with a consistent interest in textiles.(3) Among the textiles that Mrs Tweedie bequeathed to the Museum were three 18th-century English silks, some pieces of lace and a ‘Stuart needlework picture’, which was displayed on the wall in her drawing room. The file offers no further information about the original provenance of the embroidery except that it had contained a note on the reverse, presumably an imaginative leap by Mrs Tweedie, stating that the picture may have been created by a nun.

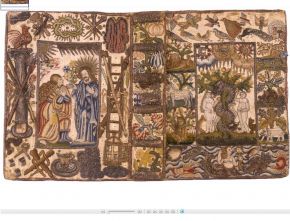

Figure 2. The Nativity, embroidered picture, unknown maker, England, about 1650-60, silk thread on canvas. Museum no. T.33-2002. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

In many respects, this ‘Stuart needlework picture’ bears the typical hallmarks of 17th-century English domestic embroidery.(4) Embroidered in simple tent stitch, its size, colours, silk thread, technique and many iconographical details, such as the attention to the natural world, are characteristic of countless embroidered pictures created during the middle of the 17th century, when women and girls were actively encouraged to devote themselves to needlework as a means of personal and domestic improvement. The composition is undoubtedly English; the absence of perspective, its hilly landscape, stylised building in the background and method of representing birds as small black crosses can all be found in other English embroideries from this period, and distinguish this object from needlework of so-called Franco-Scottish origin.(5) Another embroidery in the V&A’s collection depicting scenes from the Birth of Christ shows marked parallels (fig. 2), while a further example in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, includes comparable representations of buildings, birds and insect life (fig. 3).

Figure 3. Susanna and the Elders, embroidered picture, unknown maker, England, mid-17th century, silk and metal thread on canvas. Museum no. 64.101.1300. © Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Encouraged by contemporary didactic literature such as Richard Braithwait’s The English Gentlewoman (1641), Stuart women actively participated in a Protestant culture that celebrated the female role of virtuous homemaker. An important characteristic of women’s domestic piety was their contribution to the ‘household store’ - the material culture of the home - through needlework. According to Ruth Geuter, ‘the identification of needlework, particularly embroidery, as creative, virtuous, morally beneficial, and indicative of female achievement appears to have reached a zenith in print in the years before the English Civil Wars, a time when the fashion for making domestic pictorial embroideries was developing’.(6)

Since needlework was supposed to provide women with a means of pious instruction and a model of exemplary conduct, embroiderers often depicted biblical scenes of virtuous or heroic women. Befitting an art form that was publicly deemed a standard marker of idealised, and thus homogenous, femininity, the range of acceptable and prescribed themes was narrow. We know of approximately 1000 surviving pictorial embroideries (although many more exist in private collections) and of the 959 identified subjects or stories catalogued by Geuter, 43% depict biblical scenes.(7) The most popular designs feature the stories of Esther, Susanna, Judith and Jael, while other Old Testament narratives, such as the story of David and Bathsheba, are also well represented. Comparison of these extant examples reveals marked visual similarities, both within the central subjects, which often borrow ‘iconic poses’ from illustrated literature,(8) and also in ubiquitous incidental details such as plants, flowers and animals.(9)

The process by which women were taught and encountered designs, often mass-produced from prints and pattern books, compounded the relatively small canon of approved images.(10) Compositions were also created by professional pattern drawers, who supplied canvases with an outline image for the embroider to complete at home. This is not to imply that women exercised no control over their choice of design, as patterns could also be commissioned or invented by the embroiderer. Indeed contemporary sources proudly attest to individuals inventing their own designs. The Elizabethan diarist, Grace Sherrington (1552-1620), later Lady Mildmay, recorded in her journal, ‘every day I spent some tyme in works of myne own invention, without sample or pattern before me and to drawe flowers and fruit to their lyfe with my plummet upon paper’.(11) Nonetheless, comparison of dozens of embroideries supports Mary Brooks’s assertion that ‘seventeenth-century taste appears to have valued ingenuity in the creation of embroidered images more than originality in their selection’.(12) As such, dating embroidery precisely can be difficult, since throughout the 17th century the most popular copied patterns were consistently reproduced.(13)

While adhering to many of the formal conventions that we expect from 17th-century English domestic needlework, the V&A Magdalene appears to be completely unique. Its composition, iconography and subject matter are unlike any other known piece of early modern embroidery.(14) This image of the Magdalene – and with her long hair, naked breasts, jar of ointment and holy book it is unmistakably she – stands alone amongst the hundreds of surviving images that women embroidered to demonstrate their skill and beautify their homes. As discussed below, Mary Magdalene retained her place as an important female saint and exemplary figure long after the Reformation, but she is simply not part of the usual repertoire of embroidered images.

Both contemporary treatises and modern interpretations equate the repetition of standard religious themes with women’s conformity to societal expectations. As Lena Cowen Orlin writes, ‘In surviving pieces of work the themes are sufficiently redundant to demonstrate that women did follow the available patterns, most often from hoary Old Testament stories.’(15) Whether or not we view, with Orlin, needlework as an explicit instrument of social control, it has undeniable links with women’s wider domestic environments. Since the V&A Magdalene does not fit easily into established understandings of embroidery’s meaning and purpose for those who created and viewed it, the object raises questions about the context in which it was worked, and the wider significance of embroidered pictures within the home.

Studying embroidery

The development of the historiography of domestic embroidery, well covered elsewhere, can be usefully summarised here by comparing the following.(16) This, from 1946, is Nancy Cabot, writing in The Bulletin of the Needle and Bobbin Club:

For one with leisure, who is interested in embroidered pictures [...] I can recommend the search for sources of design in Scriptural subjects in English needlework. It is a singular delight, involving an intimate knowledge of lovely old embroideries and an extensive study of early prints and book illustrations, with the occasional gratification of being able to fit the two arts together like pieces of a glorified picture puzzle.(17)

This, from 2010, is Susan Frye in her Pens and Needles: Women’s Textualities in Early Modern England:

This chapter, (entitled ‘Narratives of Agency in Women’s Domestic Needlework’) describes how women in the household continuously shaped their environment by creating objects that expressed their always evolving identities […] A woman’s embroidery of biblical Women Worthies allowed her to express connections with female exemplars known for their personal virtue and beauty, as well as for adventures marked by eroticism and violence, all within the socially sanctioned activity of sewing.(18)

That the historiography of embroidery has evolved from a ‘picture puzzle’, attending to the discovery and explication of the subjects of specific embroideries, to a source used to uncover early modern women’s voices and agency, is of course thanks to the continued influence of Rozsika Parker’s The Subversive Stitch and her insight that ‘to know the history of embroidery is to know the history of women’.(19)

Following Parker’s lead, scholars have continued to use women’s domestic embroidery to illuminate the mental and social worlds of women who left scant textual evidence, although these studies debate the extent to which embroidery can be considered an authentic articulation of women’s creative agency.(20) The focus remains, however, on the intellectual significance of needlework as an activity and on embroideries as the product of a dynamic relationship between subject and object at the point of creation. As such, the debate centres on two sides of the same coin: can embroidery, as Frye argues, be an insight into women’s thought processes, powers of invention, and potentially subversive identification with powerful figures; or, rather, should it be understood simply as evidence of women following generic patterns and prescriptive ideals?

This discussion starts from the notion that both scenarios can be, separately and simultaneously, correct, but that both centre on embroidering as an act or as a behaviour, and embroideries only secondarily as manifestations of ideas, rather than as material objects. Thus, the focus still remains on women’s identification with the idealised function of needlework, taking contemporary domestic treatises at face value by understanding embroidery in terms of the internalisation of exemplary roles. However subversive these exemplars may be, this approach neglects the important relationships between people and objects, and fails to consider the agency of the object as well as of its maker. While the work of Morral, Geuter and others has done much to consider embroidery within the social and domestic realms, the focus nonetheless often remains on the individual, with the assumption being that an embroidery’s influence was personal, expressing meaning on behalf of its maker.(21)

This is certainly partly correct. Some women left us very clear indications of what they believed themselves to be doing, and clearly used needlework as a means of articulating their thoughts and feelings.(22) At other times we can satisfactorily link a woman’s biography to what we take their samplers to ‘mean’.(23) Yet, we should also stress embroidery’s wider influence, which was, after all, made to be seen within the domestic sphere. We do not yet know enough about the exact uses of embroidered textiles, but as objects of high value they were used throughout the home as domestic furnishings, thus presumably neither confined to the female domain nor considered exclusively the product of female identity.

The study of Stuart needlework is sometimes evidence of what Stephen Kelly describes as ‘historiography’s wish […] to instrumentalise things, to “diagnose” them as “symptoms” of pre-existing, and therefore pre-determining culture or history’.(24) Too often embroideries are seen as symptomatic of women’s lives rather than as objects that can shed new light on the early modern household. As Peter Stallybrass et al argue, if objects are to be useful historical sources they must take precedence in the study of history, coming before the human subject as opposed to necessarily deriving from it:

The purpose […] is not to efface the subject but to offset it by insisting that the object be taken into account. With such a shift it is hoped that new relations between subject (as position, as person) and object (as position, as thing) may emerge and familiar relations change.(25)

Therefore, I would like to suggest that a useful approach is to consider the post-production of needlework, analysing embroidery after the act of embroidering has ended. If we look at the iconography and form of embroidery less as an expression of social ideals or manifestation of the embroiderer’s thoughts and feelings, and more as evidence regarding its intended use, we may gather clues about how it was perceived and, crucially, how it was incorporated into the household upon completion.

The uses of embroidered pictures

Despite anxiety about the dangers of idolatry, there is ample evidence that post-Reformation homes continued to be full of religious images. Tara Hamling has demonstrated the extent to which explicitly religious imagery survived in self-consciously Protestant domestic settings, and we know that pictorial embroideries on religious themes were worked into objects for the home, such as cushions and book coverings.(26) Women’s domestic needlework and embroidery was ‘also used to ornament bed furnishings, wall hangings, and seats for stools and chairs’.(27) There is some evidence that embroidered pictures were framed, although according to Kathleen Staple’s research there is a complete absence of documentary proof that pictorial embroideries were hung as ‘pictures’ in the modern sense of the term. While many homes did display images on the walls, the indications are that these pictures ‘were paintings and prints; no needlework or embroidery was mentioned’ in the sources. Staples concludes that the fashion for framing embroidered pictures in the late 17th century might relate to the popularity of ‘stumpwork’ – a 19th-century term used to describe raised embroidery – which would have rendered the piece impractical for domestic furnishing.(28)

As a piece of traditional ‘flat’ needlework, measuring approximately 40 cm by 46 cm, it is more probable that the V&A embroidery was worked into a cushion top. The size of the piece, as well as the border surrounding the central image, implies that this was a self-contained ‘short’ cushion top as opposed to part of a larger ‘long’ cushion, but we cannot preclude the possibility that it was worked into a larger embroidery. Moreover, this piece may have been part of a sequence; according to Hamling’s research on extent examples, ‘religious subject matter seems to have been fairly common as decoration for tapestry cushions and a set of cushions could provide a whole narrative with each cushion depicting a single episode’.(29)

Without knowing the specific nature of their use it is difficult to discern the extent to which embroidered images on a religious theme should be characterised as fundamentally ‘religious’ images. As Mary Brooks explains, ‘It is debatable how much the biblical ‘kits’, stitched by unidentifiable women […] can inform us about the religious sensibilities of the embroiderers’.(30) It is perhaps more valid to see these objects as part of a repertoire of mainstream images which existed in a culture infused with Christian stories and imagery. Cushion covers depicting biblical heroines were embroidered by women and young girls to contribute to the ‘household store’. As such they were social objects, integrated into the richly visual setting of the 17th-century home; biblical in theme rather than expressly religious in nature.

However there is also evidence that embroidered cushions had specifically religious uses. They were placed on altars and tables to support books and also served liturgical functions, even within Protestant settings.(31) Celia Fiennes, who travelled around England at the turn of the 18th century, recorded that on the altar at Canterbury Cathedral books rested on top of cushions when they were opened for use in services.(32) As such, pictorial embroideries must also have had specifically religious as well as social uses and associations.

Mary Magdalene and the embroidery

Figure 4. Geneva bible with embroidered binding, Anne Cornwallis, England, about 1650, silk and metal thread on white silk. Museum no. PML 17197.1. © The Pierpoint Morgan Library, New York

The medieval cult of Mary Magdalene was one of the most popular across Europe, making her the favourite female saint from the 13th century onwards. As the epitome of the penitent sinner, the prostitute redeemed through pious contrition and love of Christ, she served as a model for penitential associations and confraternities, and was a popular subject for medieval sermons about the necessity of repenting of lives of luxury and sin.(33) A composite figure derived from various passages in the Bible, the Magdalene provided a flexible and multifaceted character, and scholars of early modern manifestations of her cult emphasise its malleability.(34) Rather than being swept aside during the Reformation, Mary Magdalene persisted as a very popular figure within the Protestant Church; as a biblical figure, her feast day was still included within the Protestant liturgical calendar. Mary Magdalene endured because she could be adapted to suit the changing needs of both Catholics and Protestants in post-Reformation England. In the Catholic Church, she became an emblem of Catholics’ spiritual connection with Christ, while in the Protestant tradition she served as a model of the sinner reformed through personal piety and penitence.(35)

An embroidered book cover in the Morgan Library shows the Protestant attachment to Mary Magdalene in her early modern guise as repentant sinner (fig. 4). Made as the cover for a Geneva Bible, it was embroidered by Anne Cornwallis around the time of her marriage to Samuel Leigh in about 1650. The embroidery shows Adam and Eve on the front, and, illustrating the redemptive counterpoint of the New Testament to the Old, the resurrected Christ appearing to Mary Magdalene on the back. As in the V&A Magdalene, the instruments of the Passion frame the central scene.

Anne Cornwallis depicted a traditional Noli me tangere scene: the moment at which Mary Magdalene encounters the newly resurrected Christ. The scene is based on an episode in John’s Gospel, in which Mary has gone to Christ’s tomb to anoint his body, and is dismayed to find the tomb empty. Upon realising that Jesus’s body has been removed, Simon Peter and another unnamed disciple return home:

But Mary stood without at the sepulchre weeping: and as she wept, she stooped down, and looked into the sepulchre. And seeth two angels in white sitting, the one at the head, and the other at the feet, where the body of Jesus had lain. And they say unto her, ‘Woman, why weepest thou?’ She saith unto them, ‘Because they have taken away my Lord, and I know not where they have laid him.’ And when she had thus said, she turned herself back, and saw Jesus standing, and knew not that it was Jesus. Jesus saith unto her, ‘Woman, why weepest thou? Whom seekest thou?’ She, supposing him to be the gardener, saith unto him, ‘Sir, if thou have borne him hence, tell me where thou hast laid him, and I will take him away.’ Jesus saith unto her, ‘Mary.’ She turned herself, and saith unto him, ‘Rabboni’; which is to say, Master. Jesus saith unto her, ‘Touch me not; for I am not yet ascended to my Father: but go to my brethren, and say unto them, I ascend unto my Father, and your Father; and to my God, and your God.’(36)

The moment at which Jesus admonishes Mary, ‘Touch me not’, noli me tangere, marks a crucial moment in Christian theology, and forms the basis of a long tradition in Western art.(37) In Anne Cornwallis’s embroidery, its significance is seen in conjunction with the story of Adam and Eve, in a design that while based on pre-Reformation iconography is clearly ‘created […] around a coherent typological theme, which is deeply imbued with an understanding of the redemptive purposes of Scripture’.(38) The adapted re-use of printed patterns and designs throughout the 16th and 17th centuries meant there was no sudden break with much of the visual culture of the past; where imagery was deemed idolatrous and proscribed, alternatives emerged in its place.(39) As shown by Anne Cornwallis’s embroidery, the instruments of the Passion survived into the 1640s, enduring ‘in post-Reformation iconography as an acceptable substitution for direct depictions of the passion’.(40) One step removed from a direct representation of Christ’s body, the symbols of his torture evidently still had strong associations with his corporeal presence.

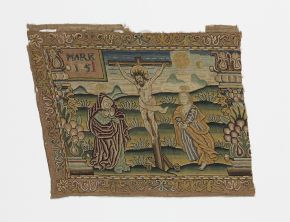

Figure 5. Scene from the Passion of Christ, part of an embroidered valance, unknown maker, France/Scotland, late 16th century, silk thread on canvas. Museum no. CIRC.402-1911. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Other pictorial embroideries dating from the late 16th and early 17th centuries also demonstrate that New Testament narratives could survive in embroidered form. Two pieces in the V&A’s collection, evidently part of a series depicting the Passion, show Christ being crowned with thorns, and the Crucifixion (figs 5 and 6). However while these objects have been cited as proof of the unproblematic continuation of traditional iconography in England,(41) their style —particularly the use of perspective and elaborate foliate columns — is more in keeping with Franco-Scottish work, and their quality suggests they are likely the work of a professional rather than an amateur embroiderer.(42) More certainly of English manufacture is a needlework picture depicting scenes from Christ’s Nativity, showing the angel’s appearance to the shepherds and their adoration at the manger (fig. 2).

Figure 6. Scene from the Passion of Christ, part of an embroidered valance, unknown maker, France/Scotland, late 16th century, silk thread on canvas. Museum no. CIRC.403-1911. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

These examples show that although unusual, embroideries depicting New Testament scenes, including images of Mary Magdalene, are not unheard of. In Anne Cornwallis’s needlework, as in other Noli me tangere imagery, Mary Magdalene is engaged within a narrative scene, a character depicted in the act of penitence, her presence contained within the confines of a story from the bible. What is most striking in the V&A’s embroidery is the prominence of Mary herself, marking this object out as radically unusual within the genre of pictorial embroidery. She is located within a conflated image of the site of Christ’s Passion and Resurrection, yet not illustrative of any specific point in the biblical narrative. The importance of narrative illustration in the Protestant justification of images was instrumental to contemporaries understanding them as portrayals of instructive ideals rather than static foci of idolatry, and this convention is adhered to without exception in the biblical embroidered pictures I have seen. Moreover, as with the other types of ‘safe’ religious images from this period, the lines of relationship in Cornwallis’s Noli me tangere exist firmly between characters within the object, rather than between the object and the beholder.(43)

Figure 7. Repentant Mary Magdalene, painting, Titian, Italy, 1560s, oil on canvas. Museum no. GE-117. © Vladimir Terebenin/The State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg

The V&A embroidery sits within a different visual tradition from that of English pictorial embroidery, being more easily comparable to the depictions of Mary Magdalene as a penitent in the wilderness that became popular during the early 16th century. Exemplified by Titian’s sexualised, Venus-like pose, which became the prototype for images of the Magdalene throughout the 17th century (fig. 7), Mary had evolved from a hirsute ascetic, in the style of St Jerome, to a become more sexualised figure whose past, bodily sins were bound up with her physical appearance.(44)

Images from paintings and prints did filter down to form the basis of patterns for embroidery, and while no clear print source has been found, a popular image of the penitent Magdalene in the wilderness could have been adapted and simplified either by a professional draughtsman, or the embroiderer herself. (figs 8 and 9). The needlework picture does not show any traces of an outline drawn by a professional pattern drawer, although given its good condition there are few places where the canvas is exposed by worn thread (fig. 10). Alternatively, if the image had been transferred to the canvas by the embroiderer through pricking and marking with pounce, any vestiges of the original outline would have long since disappeared.

Figure 8. The Magdalene Repentant, print, Francesco Cozza, Italy, 1650, etching. The Illustrated Bartsch. Vol. 41, Italian Masters of the Seventeenth Century (New York: Abaris Books, 1987). © ARTstor

Figure 9. The Penitent Magdalene, print, Wenceslaus Hollar after Holbein, England, 1638, etching. University of Toronto

Figure 10. Verso of Mary Magdalene Surrounded by Instruments of the Passion, embroidered picture, unknown maker, England, mid-17th century. Museum no. T.18-1940. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Prints are not the only possible source of inspiration for the embroidery’s design. The iconographic similarities between the Magdalene and other nude female figures means that her pose could also have been adapted from an entirely different image. Her reclining form bears similarities to emblematic female figures representing fecundity, as in the dishes made in Southwark during the 17th century (fig. 11), and personifications of the theological virtues such as those found in a set of Italian hanging pockets now in St John’s House Museum, Warwick. The figure representing Faith here holds a book and a cross.(45)

Figure 11. Dish decorated with figures emblematic of 'Fecundity', unknown maker, earthenware, Southwark, London, about 1635, tin-glazed earthenware, press-moulded and painted. Museum no. C.32-1928. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Whatever her source, while the embroiderer has taken care to include the Magdalene’s traditional identifying symbols — long hair, a jar of ointment, a skull and a cross — there is a marked difference between typical imagery and the embroidered version. In the latter, the cross is so large it appears less an attribute than a context; Mary is apparently present in the landscape of Christ’s sacrifice, rather than situated in an anonymous wilderness. This is a slightly contentious point, as early modern embroiders adopted a very flexible approach to relative size. Mary Brooks attributes incongruities in scale to the embroiderers’ method of copying designs from printed sources through pricking rather than scaling, but pattern books such as Shorleyker’s A schole-house for the needle (1632) did include grids for scaling, and this would have been a fairly simple section to make smaller.(46)

Figure 12. The Penitent Magdalene, painting, unknown maker, England, 1570-99, oil on panel. Museum no. 1430471. © National Trust Images

Therefore while needlework always maintained an independent aesthetic taste and formal tradition that cannot be reduced to available print sources, the composition of the image arguably also distances this embroidery from typical penitent Magdalene iconography. Engaging its beholder, it makes sense less as a narrative illustration of a biblical scene, or exemplar of moral behaviour, than as a devotional image. In doing so, it has the flatness of an icon, an invitation for the more metaphysical kind of contemplation associated with affective Catholic worship, and with the Magdalene in her role as the conduit of religious experience.

Catholic devotion to Mary Magdalene

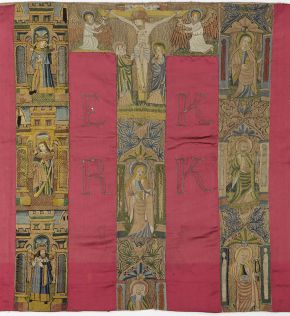

Figure 13. Embroidered altar frontal, unknown maker, England, about 1600, satin with silk embroidery. Museum no. 817-1901. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

While her popularity was not confined to Catholics, Mary Magdalene has a distinguished place in Counter-Reformation worship. Recent scholarship has focused on the Magdalene’s role as a physical connection to the body of Christ, analysing how her loss of Christ’s body served as a parallel to Catholics’ loss of his sacramental presence. As Patricia Badir explains, ‘In diverse early modern sources, the Magdalene is an exemplar of visible things able to give imaginative form to the events central in Christian culture […] [She has the] ability to materialise the immaterial, lending appreciable shape to the experience of faith’.(47) This conceptualisation of the Magdalene was particularly resonant with English Catholics of the early modern period as ‘Mary Magdalene and English Catholics shared a common trial of faith — the loss of Christ’s body’.(48) In this way, the figure of the Magdalene served as a focal point for Catholics, a powerful symbol of enduring Christian memory.

One

way in which English Catholics maintained an active memory of their

proscribed faith was through objects. Despite widespread destruction of

Catholic material culture, we know from contemporary inventories that

some households maintained the material trappings of Catholicism,

including paintings and textiles. The Northampton home of the Catholic

Earl of Northampton, Henry Howard, contained tapestries of the Story of

Christ, and images of the Virgin Mary, St Francis, Christ holding his

cross, and the three Marys at Christ’s tomb.(49) A late 16th-century

painting on panel now in the National Trust’s collection at Chastleton

House shows a penitent Magdalene reading, although it is unknown whether

the painting formed part of the collection of the Catholic – and

Gunpowder Plotter – Robert Catesby who owned the original Chastleton

(fig. 12). Some Catholic houses also included ‘hiding places for the

altar furniture, books, vestments and other necessary paraphernalia’ for

Catholic mass.(50) These objects were often richly embroidered with

images of saints, such as an altar cloth decorated with 16th-century

needlework, including an image of Mary Magdalene, thought to have come

from the Catholic Huddlestone family of Sawston, Cambridgeshire (fig.

13).

Another means of keeping the Catholic faith alive was through transmission of texts. Both men and women were engaged in circulating illicit religious ideas via manuscript and print networks, and extant manuscripts and printed texts show how such poems were copied and reproduced, as well as adapted and expanded.(51) Helen Hackett’s recent article on women’s participation in mid-17th-century Catholic manuscript networks draws attention to the literary and meditational practices of the Counter Reformation in England. Taking as her point of departure a verse miscellany by Constance Aston Fowler (1621?-64), Hackett demonstrates how English Catholics transmitted and added to ‘Catholic traditions of the past’ by engaging in Loyolan ‘composition of place’. As the focus for affective veneration of Christ, Mary Magdalene enjoyed a privileged position within such manuscripts, and ‘verses to [her] written by English Catholics after the Act of Uniformity were among the most popular devotions to be circulated among English Catholics’.(52)

One such form of affective veneration was The Poetry of Tears, an explicitly Catholic form of meditational devotion to the Magdalene, most notably expounded by the Jesuit priest Robert Southwell.(53) Southwell was executed for treason in 1595, but his poems were reprinted at least nine times by the 1640s, including twice by clandestine presses, and were undoubtedly in covert circulation throughout the 17th century. His treatises included Saint Mary Magdalen’s funeral Teares for the death of our Saviour (1591) and a poem, Marie Magdalens complaint at Christ’s death. Together with Gervase Markham’s Marie Magdalens Lamentations for the Losse of her Maister Jesus (1604), John Sweetnam’s Mary Magdalens Pilgrimage to Paradise (1617), Saint Marie Magdalen’s Conversion (1603) by an author known only as I.C., and numerous poems by the exiled Catholic layman Richard Verstegan (d. 1636), they form the basis of a corpus of work centred on the Magdalene’s grief and sense of loss at the discovery of Christ’s empty tomb.(54) She is, as Markham puts it, ‘mournfully searching for something real to hold’. As English Catholics too sought some tangible symbol of their faith, they imaginatively participated in what Michael O’Connell has called the ‘incarnational religious aesthetic’ of early modern Catholicism.(55) Rather than focusing on Mary’s role as penitent, the poetry of tears instead emphasises her power as ‘a worldly link to the resurrection’.(56)

The explicitly bodily nature of the V&A’s embroidery emphasises the Magdalene’s connective presence to the sacrificial body of Christ, evoked through the surrounding instruments of the Passion, and it is tempting to ask whether contact with such an object could make the beholder feel closer to Christ’s comforting presence. Sophia Holroyd has documented examples of women using needlework ‘as both subject and structuring device for deep-focused meditation’, which raises the possibility that the embroidery could have functioned within the context of affective Catholic worship and the aesthetics of recusant domestic space.(57) In the absence of official, public outlets of Catholicism, ‘the household was the crucial site of both observance and resistance’ and women often played an integral role in ensuring households maintained Catholic devotions. In many documented cases, ‘the husband would conform outwardly, attending church to protect property and maintain access to office, while the wife would oversee Catholic devotions in the home and maintain the family’s Catholic identity’.(58)

By its very nature covert religious practices are hard to unearth and complex to interpret. We have no way of knowing how many similar embroideries of the Magdalene may have been made and have been lost or destroyed over time. However if we, with McClain, are ‘willing to look in new directions, for new incorporations of the Magdalene in larger patterns of worship’ the V&A’s embroidery might provide further clues as to how material objects made by women contributed to Catholic devotion in the 17th century.(59) While a piece of domestic needlework lacks the full aesthetic and imaginative impact we today associate with artistic production, it is important not to underestimate the power of an image like this in the post-Reformation period, nor to forget that Catholics risked their lives to keep the material culture of their faith, as the tools and token of worship were channelled into a more ‘adaptive, transportable, clandestine devotional practice’.(60)

Conclusion

In an effort to make sense of this unusual object, consisting of unfamiliar design, anonymous manufacture, uncertain date and unknown provenance, this discussion has separated it from both modern and historic assumptions surrounding women’s needlework. By focusing on the visual qualities of the embroidery-as-object, rather than the rhetoric surrounding embroidery-as-activity, it proposes an analytical model as an opportunity to expand the historiography of embroidery design into something more than the history of embroidery.(61)

I have no wish to deny women’s intellectual or creative agency in their needlework, and presume that like most forms of production there are degrees to which individuals conceptualised it as a form of expression; embroidery was neither simply ‘decorative brainwashing’ nor purely authentic voice. Equally, I have no doubt that many women did embroider exemplary female figures as a means of identifying with heroic role models. Yet this object shows the limitation of this interpretation; if this Magdalene invites identification with an idealised role, it is as psychological attachment rather than moral exemplarity.

Moreover,

the association of embroidery with women’s history has meant that

embroideries are often considered only in the realm of the feminine, as a

‘potential means to investigate women’s

history’ rather than the history of which women are a part, and in which

they suffer from anonymity.(62) In the absence of biographical

information about many makers of material culture, there has to be an

alternative way of addressing such objects. If there is not, anonymous,

domestic objects (and their often female creators) are

disproportionately absent from our historical understanding. Considering

embroidery as part of the domestic space inhabited by both genders adds

to a wider story which encompasses religion, politics, and wider

society. As Dolan argues, ‘Viewing the household as the base of

operations for Catholics offers yet another challenge to the notion that

the private was a distinctly separate or apolitical realm in the early

modern period.’(63) This embroidery does not alone prove anything;

rather it contributes to a process by which the layering of small,

unremarkable objects creates a clearer picture of the hidden

understandings that are expressed through daily, conscious and

unconscious interaction with things.(64)

1. The daughter of Dr George Harley, an eminent Scottish physician, Ethel Brilliana Harley married Alexander Tweedie in 1887. Following the death of both of her sons (the younger killed in action in 1916, the elder in an aircraft accident while serving in the RAF in 1926), she wished her collection to be used for the public good: ‘I think I had told you that both of my sons had fallen for this country and that therefore I wanted to give everything I could to the country for the furtherance of education’. Letter from Mrs Alec Tweedie to the V&A, February 6, 1927. V&A object file MA/1/A313. For more on her activities as Secretary of the British Women’s Produce League see ‘Women’, The Nursing Record and Hospital World, April 25, 1896, 343.

2. V&A object file MA/1/A313. One can only speculate upon Mrs Tweedie’s interest in this embroidery, but the iconography of Christ’s Passion may have related to her book about the Bavarian Oberammergau Passion Play. Ethel Alec Tweedie, The Oberammergau Passion Play (London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co., 1890).

3. Mrs Tweedie’s interest in the ‘womanly’ accomplishment of embroidery could bring her some frustration. The introduction to My Table-cloths humorously notes that as someone who had ‘written sixteen volumes by the sweat of my brow, to say nothing of new editions and translations, and [having] done a few minor things in the world beside stitching’, she was ‘cut to the heart to find my name associated with nothing but table-linen’. Ethel Alec Tweedie, My Table-cloths; A Few Reminiscences (New York: George H. Doran, 1916), 1.

4. Some clarifications of vocabulary are necessary here. By ‘domestic’ I mean made in the home for use in the home rather than merely made in the home for sale elsewhere. There is also a technical distinction between embroidery and needlework though I will use the terms interchangeably — strictly speaking, embroidery is embellishment on a fabric background; this picture is needlework, which denotes stitching on canvas. Finally I am making an assumption about the gender of the embroiderer. While professional embroidery was certainly done by men, who sometimes worked from their homes, domestic work made in the home for the home was characteristically done by women.

5. For these observations I am grateful to Clare Browne, Senior Curator in Textiles and Fashion at the V&A, without whose expertise and generosity this article could not have been written. For examples of Franco-Scottish embroidery, see Maria-Anne Privat-Savigny, Quand Les Princesses D’Europe Brodaient (Paris: Réunion des Musées Nationeaux, 2003).

6. Ruth Geuter, ‘Embroidered Biblical Narratives and Their Social Context’, in English Embroidery from the Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1580-1700, ed. by Andrew Morrall and Melinda Watt (New York: Yale University Press, New Haven and The Bard Graduate Center, 2008), 63.

7. Ruth Geuter, ‘Women and Embroidery in Seventeenth-Century Britain: The Social, Religious and Political Meanings of Domestic Needlework’, (PhD thesis, University of Wales, 1996): vol. 1, 276-7, Table 1, List of Catalogued Subjects; vol. 2, 460-98, Appendix G, Catalogue of 17th-century Embroideries.

8. Geuter, ‘Embroidered Biblical Narratives’, 63.

9. Andrew Morrall, ‘Regaining Eden: Representations of Nature in Seventeenth-Century English Embroidery’, in English Embroidery from the Metropolitan Museum of Art, ed. by Morrall and Watt, 79.

10. The V&A’s National Art Library holds 60 original embroidery books from the period 1523-1700, including the only extant copy of Richard Shorleyker, A schole-house for the needle, (London, 1632).

11. Quoted in Mary M. Brooks, English Embroideries of the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries: In the Collection of the Ashmolean Museum (Oxford: Ashmolean Museum, 2004), 13.

12. Brooks, English Embroideries of the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries, 22.

13. Some of the most popular patterns were adapted from Continental print sources, notably Thesaurus sacrarum historiarum veteris testamenti (Antwerp: Gerard de Jode, 1585), a book of biblical stories.

14. The author has consulted numerous collections of embroideries and a variety of specialists in the field, including curators of textiles at the V&A, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, and Ashmolean Museum, Oxford.

15. Lena Cowen Orlin, ‘Three Ways to be Invisible in the Renaissance: Sex, Reputation, and Stitchery’, in Renaissance Culture and the Everyday, ed. by Patricia Fumerton and Simon Hunt (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1999), 189.

16. For example, Susan Frye, Pens and Needles: Women’s Textualities in Early Modern England (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2011), 162-5.

17. Nancy Graves Cabot, ‘Pattern Sources of Scriptural Subjects in Tudor and Stuart Embroideries’, Bulletin of the Needle and Bobbin Club 30 (1946): 3.

18. Frye, Pens and Needles, 116-8.

19. Rozsika Parker, The Subversive Stitch: Embroidery and the Making of the Feminine (London: The Woman’s Press Ltd, 1984).

20. In contrast with Parker and Frye, Lena Cowen Orlin sees the silent needlework done by women as symptomatic of ‘self-abnegation’ rather than autonomy. Orlin, ‘Three Ways to be Invisible in the Renaissance’, 185.

21. See Morrall and Watt, English Embroidery from the Metropolitan Museum of Art, passim.

22. For examples of women’s writing ‘explaining’ their embroideries, see Brooks, English Embroideries of the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries, 15-16.

23. See Michael Bath, Emblems for a Queen: The Needlework of Mary Queen of Scots (London: Archetype Publications, 2008).

24. Stephen Kelly, ‘In the Sight of an Old Pair of Shoes’, in Everyday Objects: Medieval and Early Modern Material Culture and its Meanings, ed. by Tara Hamling and Catherine Richardson (Surrey, England and Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2010), 62.

25. Margreta de Grazia, Maureen Quilligan and Peter Stallybrass, eds, Subject and Object in Renaissance Culture (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996), 5.

26. Tara Hamling, Decorating the 'Godly' Household: Religious Art in Post-Reformation Britain (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2010).

27. Kathleen Staples, ‘Embroidered Furnishings: Questions of Production and Usage’, in English Embroidery from the Metropolitan Museum of Art, ed. by Morrall and Watt, 32.

28. Morrall and Watt, English Embroidery from the Metropolitan Museum of Art, 34.

29. Hamling, Decorating the 'Godly' Household, 211.

30. Brooks, English Embroideries of the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries, 15.

31. Santina Levey, The Embroideries at Hardwick Hall (Great Britain: National Trust, 2007), 31.

32. Celia Fiennes, Through England on a Side Saddle in the Time of William and Mary (London: Field and Tuer, The Leadenhall Press, 1888), 103.

33. I have relied heavily on Susan Haskins, Mary Magdalene: Myth and Metaphor (London: Harper Collins, 1993). For the medieval cult of the saint see chapter V, ‘Beata Peccatrix’.

34. Patricia Badir, The Maudlin Impression: English literary images of Mary Magdalene, 1550-1700 (Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press, 2009), 2.

35. Lisa McClain, ‘“They have taken away my Lord”: Mary Magdalene, Christ’s Missing Body, and the Mass in Reformation England’, The Sixteenth Century Journal 38. 1 (2007): 81.

36. John 20:1-18, King James Version.

37. For a history of Noli me tangere imagery, see Barbara Baert ‘The Gaze in the Garden: Body and Embodiment in “Noli me tangere”’, Nederlands Kunsthistorisch Jaarboek (2008): 15-39.

38. Morrall, ‘Regaining Eden’, 85.

39. Lists of print sellers’ stock in the 17th century show that old print sources were continually recycled. Tessa Watt, Cheap Print and Popular Piety (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991), 82-4.

40. Watt, Cheap Print and Popular Piety, 175-6.

41. Hamling, Decorating the 'Godly' Household, 213.

42. I am grateful to Clare Browne for her observations on this point.

43. Watt, Cheap Print and Popular Piety, 186.

44. For detailed information about the evolving identity of Mary Magdalene, see Haskins, Mary Magdalene: Myth and Metaphor, particularly chapter VII, ‘The Weeper’.

45. Mary M. Brooks and Sonia O'Connor, ‘The Use of X-radiography in the analysis and conservation documentation of a set of seventeenth-century hanging wall pockets’, in X-Radiography of Textiles, Dress and Related Objects, ed. by Sonia O’Connor and Mary Brooks (Oxford: Elsevier Ltd, 2007), 231-6.

46. Shorleyker, A schole-house for the needle.

47. Badir, The Maudlin Impression, 14-15.

48. McClain, ‘“They have taken away my Lord”’, 78.

49. Sophia Jane Holroyd, ‘Embroidered rhetoric: the social, religious and political functions of elite women's needlework, c.1560-1630’, (PhD thesis, University of Warwick, 2002), 160.

50. Holroyd, ‘Embroidered rhetoric’, 201.

51. For example, in an early 17th-century manuscript version of Mary Magdalens Lamentations for the Losse of her Maister Jesus in the Cheshire City Archive is a copy of Gervase Markham’s 1604 versification of Robert Southwell’s Mary Magdalens Tears for the death of our Saviour (1591). McClain, ‘“They have taken away my Lord”’, 77.

52. Helen Hackett, ‘Women and Catholic Manuscript Networks in Seventeenth-Century England: New Research on Constance Aston Fowler’s Miscellany of Sacred and Secular Verse’, Renaissance Quarterly 65. 4 (2012): 1099-100. See also: Patrick Collinson, Arthur Hunt and Alexandra Walsham, ‘Religious Publishing in England 1557–1640’, in The Cambridge History of the Book in Britain. Volume 4: 1557–1695, ed. by John Barnard and D. F. McKenzie, with the assistance of Maureen Bell (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002), 29–66; Alexandra Walsham, ‘“Domme Preachers”? Post-Reformation English Catholicism and the Culture of Print’, Past and Present 168 (2000): 72–123.

53. Alison Shell, Catholicism, Controversy and the English Literary Imagination, 1558-1660 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005), 57.

54. McClain, ‘“They have taken away my Lord”’, 82.

55. Michael O’Connell, The Idolatrous Eye: Iconoclasm and Theater in Early Modern England (New York: Oxford University Press, 2000), 47.

56. McClain, ‘“They have taken away my Lord”’, 89.

57. Holroyd, ‘Embroidered rhetoric’, 155-6.

58. Frances Dolan, ‘Gender and the “Lost” Spaces of Catholicism’, The Journal of Interdisciplinary History 32. 4 (2002): 652-4.

59. McClain, ‘“They have taken away my Lord”’, 81.

60. Dolan, ‘Gender and the “Lost” Spaces of Catholicism’, 664.

61. This is in contrast with Orlin, who considers her work on the subject to outline ‘less historical practice than cultural myth about the role of stitchery’. Orlin, ‘Three Ways to be Invisible in the Renaissance’, 199.

62. Ruth Geuter, ‘English Figurative Embroideries’, in Gender and Material Culture in Historical Perspective, ed. by Moira Donald and Linda Hurcombe (Hampshire and New York: St. Martin's Press, 2000), 106.

63. Dolan, ‘Gender and the “Lost” Spaces of Catholicism’, 655.

64. See Patricia Fumerton on ‘successive anecdotalism’, in ‘Introduction: A New New Historicism’, in Renaissance Culture and the Everyday, ed. by Fumerton and Hunt, 4.

Issue No. 7 Summer 2015

- Editorial

- An Unusual Embroidery of Mary Magdalene

- Printed Sources for a South German Games Board

- ‘Sawney’s Defence’: Anti-Catholicism, Consumption and Performance in 18th-Century Britain

- A Weft-Beater from Niya: Making a Case for the Local Production of Carpets in Ancient Cadhota (2nd to mid-4th century CE)

- Out of the Shadows: The Façade and Decorative Sculpture of the Victoria and Albert Museum, Part 1

- Gestures, Ritual & Play: Interview with Liam O’Connor

- Contributors