With only five sleeps until Christmas, things are in full festive swing at the V&A. The main entrance has been given a period makeover by StudioXAG’s Victoriana ironwork Christmas tree, the V&A Shop has come through with the perfect blend of class and culture for my auntie Karalyn’s Christmas card, and the Benugo cafe is once again offering delicious seasonal fare. Tis’ the season to be Jolly! Yet, to paraphrase everyone’s favourite little green guru and Grinch lookalike [i]: Jollity leads to gift giving, gift giving leads to desire, and desire leads to conspicuous consumption.

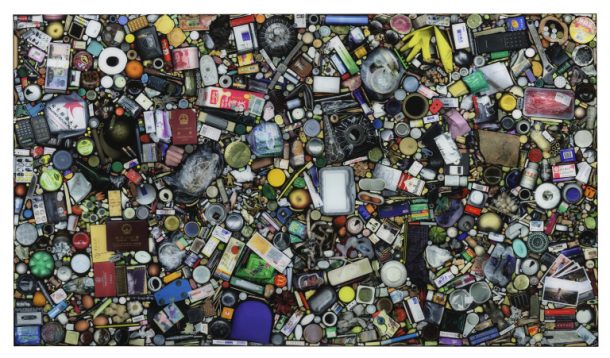

A recent rotation of the central display in our T.T. Tsui gallery of Chinese Art touches on this Dark Side of the Force Christmas Spirit. The work in question is ‘My Things No.1 《我的东西之一》(2001), a substantial photographic print by the acclaimed contemporary Chinese artist Hong Hao 洪浩 (b.1965). The curatorial resonances between Hong Hao’s work and our collective predilection for mass consumption at this time of year are more accident than vision. Nonetheless, when searching for the perfect something for that someone special in the V&A shop, it’s well worth walking ten feet into the Tsui gallery to take a look at Hong Hao’s examination of human relationships to resources.

Photographic colour print, scanning

Purchased with the support of the Cecil Beaton Fund

FE.10-2016

Seen as a whole, My Things No.1 is an overwhelming array of close-packed colours and textures. A panoply of stuff suspended against a black void. The complexity and contrast in the composition forces your eye to jump from one object to another. Sometimes this prompts surreal juxtapositions. Sometimes close affinities. The porous surface of a broken brown brick. Cellophane wrapped strips of lean pork. A red and gold pack of Chunghwa cigarettes. A red and white pack of Marlboros. Mao’s profile on a crisp wad of hundred yuan notes. Sting’s face on the cover of his best of album Fields of Gold. Thirteen vacuum packed clams. A fist.

My Things No.1 includes a bewildering array of material. It is part of an extended series documenting consumption in contemporary life. Some of the later works in Hong Hao’s series show more homogenous masses of material, artfully arranged into deeply satisfying constellations of shape and colour. In My Thing’s No.1, the first work in the series purchased by the V&A in 2016 with the support of the Cecil Beaton Fund, Hong Hao shows a disparate array of objects indicative of contemporary consumption. He collected these objects over the course of a year, scanning them, and reassembling the scanned images into macro-collages.

Hong Hao has said: ‘By flattening the third dimension, scanning embodies a calm observation without any pre-judgement, a plain testimony, a relevant context for aesthetic exploration. Throughout the process of scanning, an intimate relationship is established among human and things, things and machine. In this connection, scanning has become a routine of my everyday life.’ [ii]

The mechanical neutrality of Hong Hao’s scanner strips things of their context. They float in a visual vacuum. Volume is lost as everything presses against the surface of the photograph. His recording process makes for an unconventional intimacy with waste. Every discarded object we see has passed through the artist’s hands, and has then been altered and positioned to suit an aesthetic programme. They no longer exist in space, making it difficult to perceive their depth and scale. Reassembled in the single object of the photograph, these pieces of everyday life take on new relationships within the frame of My Things No 1. As Hong Hao’s statement above makes clear, one of these key relationships is aesthetic, exploring shapes, colours and textures. However, if you look closely at the things within the photograph they weave a web of potential meanings. These meanings come from multiple sources. Some are based on what these things were used or made for. Some come from Hong Hao’s aesthetic interventions in objects, twisting them into unfamiliar angles that make us look longer, peer closer. Some meanings come from the connections the viewer makes between objects. Yet the viewer can only make these connections because of what Hong Hao chose to include in this vast sea of stuff. I want to pick up on three things this rich representation of material and consumption addresses, looking at examples specific to China in the late 20th and early 21st centuries.

Milk and Tea

In the top left of the photograph a tetra pack milk carton has been scanned on its front. It bilingually announces itself as: ‘Bright’ (光明) brand ‘High iron fresh milk’ (高铁奶). Hong Hao’s choice to scan this familiar, customer facing surface makes it clearly recognisable. It can’t be anything but a milk carton. This angle also brings out its pink, white and yellow laminated surface, asserting how branding has reshaped Chinese consumption since the introduction of market forces into China’s economy in the 1980s. There is also a playful dimension to the milk carton’s presentation. Hong Hao has used a two yuan note to cover the third character on the logo: nai 奶 (milk). The two visible characters read gao tie 高铁: ‘high iron’. This is also the conventional term for ‘high speed rail’, a contraction of gaosu tielu 高速铁路. Perhaps the pun is an allusion to breakneck development? In 2001 when Hong Hao compiled My Things No.1 China was also launching its first high speed rail train: the Blue Arrow (蓝箭), running at 235.6 kph from Guangzhou to Shenzhen. [iii] On the carton the Chinese subtitle, next to the partially obscured logo, proudly declares that Bright Milk has added lactoferrin (添加乳铁蛋白). This iron-binding amino acid is a key component of the body’s immune system. At an elemental level the PRC’s 21st century transport infrastructure and the bodies of the nation’s children were built and enhanced with the same metal.

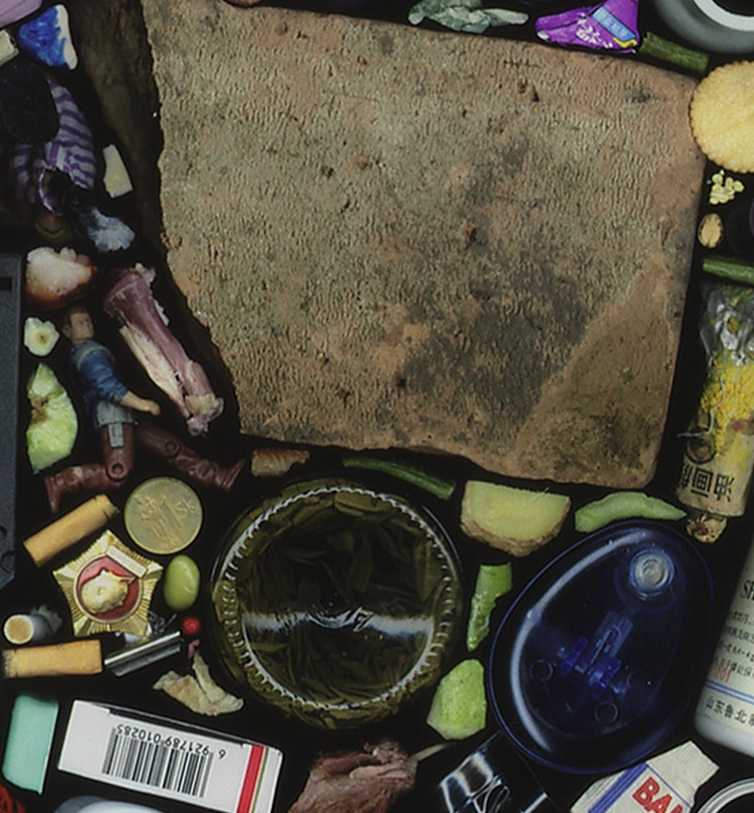

In the centre right of the photograph, beneath the broken brick, Hong Hao’s positioning of other objects requires more intensive looking. It is the base of a jar in which someone has brewed tea. The scan captures the saturated leaves that have and sunk to the base of the vessel. The liquid will be bitter. Stewed. Looking at the jar from underneath it is not easily recognisable. Hong Hao’s choice of angle in this detail emphasises a process of consumption. It shows us how ordinary Chinese people brew and drink tea. Yet the framing of the object partially obscures its legibility. Unlike the milk carton, it is not instantly recognisable. The milk carton is corporate, commercial and mass produced. The jar is unbranded, domestic, and intimate.

Mao and McDonalds

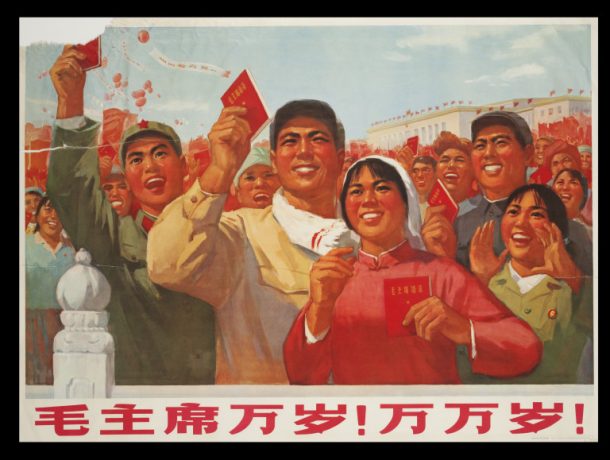

Other contrasts are sharper, and more direct. Just to the right of the jar of tea a Chairman Mao badge shows the Great Helmsman in profile against a red glass ground, set in a gold star. In the lower left of centre another badge stands out for its red and yellow colour palette. This is a button from McDonalds™. The presence of the Mao badge in Hong Hao’s work is a material reminder of China’s relatively recent embrace of Maoist ideology, which diametrically opposed itself to the Capitalist system exemplified by an “Imperialist America”. The Chairman died in 1976. Market orientated reforms that begun in the 1980s have completely reshaped China in the subsequent decades. Forty years after Mao’s death, Golden Arches are a not uncommon sight in Chinese cities. They announce a willingness to consume US led capitalist globalisation, or at least to try the 1,440 calorie meals it has to offer. [iv]

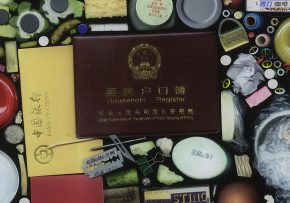

The Household Register System (Hukou)

Others objects carry associations less readily legible to the V&A’s non-Chinese audiences. A Household Register (Jumin Hukou Bu 居民 户口簿) sits in the lower left of the picture. Its bilingual text is printed under a framed image of the Tian’anmen Gate, a symbol of the Chinese state. The gold text contrasts with a deep maroon cover. Even if you don’t know what the document is for, it’s typography and imagery tells you it is clearly something official. Something to be valued and taken care of. The Household Register system dictates who can use public services in China. You only have full access to healthcare and education in the area where you are registered. The huge numbers of migrant labourers who have moved from the countryside to the city are significantly affected by this system. If they have a register from another municipality, particularly from the countryside, these economic migrants are cut off from local services. They have to pay inflated healthcare costs. Their children can’t go to local schools. Often these children have to live apart from their parents. The tension between an emotional need for proximity and the economic necessity of distance has been met with some inventive solutions. The V&A’s Rapid Response Collecting programme recently acquired a cuddly monster called Mon Mon, who plays children voice messages sent by their parents sent via WeChat. This pink ball of fluff and wires is essentially an adorable zoomorphic answer phone that makes the best of a bad situation. Yet he does not resolve it.

Designed by 1 More Design

CD.25-2015

The imbalance the Household Register system creates between migrant labour and the locally registered populations in urban centres is one of the greatest challenges China faces in the twenty first century.

Hong Hao’s photograph highlights choices over what to consume made by billions of people in China’s fast changing society. Drink strong tea from a glass jars or branded milk with added iron? Smoke cheap domestic Chunghwa fags or splash out on expensive foreign Marlboros? Cook lean pork at home or go out for a Big Mac Meal. There is web of connections between things across the surface of the photograph, prompting us to think about what, how and why we consume. Take a moment out from your Christmas shopping to come and look at it, you might be surprised by what you see.

[i] Yoda action figure, made by Palitoy, 1981, part of the Castle Collection of space toys. Collection of V&A Museum of Childhood.

[ii] Excerpt from Hong Hao’s notes, published in Hong Hao catalogue, Pace Beijing, 2013, p. 35

[iii] https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/China_Railways_DJJ1

[iv] Big Mac, large fries, and large chocolate milkshake. http://www.mcdonalds.co.uk/ukhome/meal_builder.html

Every place were celebrated their Christmas in a vast way. When you look at UAE you will find the magic of flowers. They were mainly concentrated to make it as a heaven to people feeling great on their life.