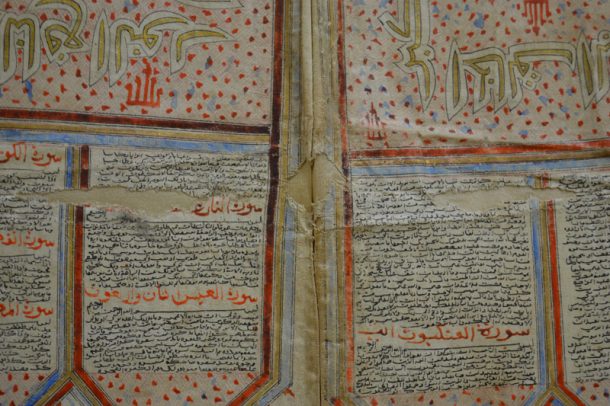

The Fabric of India exhibition focused entirely on textiles and featured around 200 objects ranging from the third to the twenty-first century. Amongst the many V&A textiles prepared for the exhibition was a rare Islamic Talismanic shirt that was displayed alongside other Indian sacred textiles representing the main faiths of the people of India. The shirt, T.59-1935 (Figure 1), which was given to the Museum in 1935 but had never been on display, is a remarkable object for upon it, carefully inscribed, is the entire text of the Qur’an! The Indian Bihari style used to write the Arabic script has helped to date the shirt to the fifteenth or sixteenth century during the period of the Delhi Sultanate (1206-1526). The text of the Qur’an is sacred to Muslims and is believed to have protective powers. The verses in large script on this shirt suggest it was made for a warrior to protect him in battle. There are certainly signs that the shirt has been worn, for the areas under the arms are damaged from wear and the ink and paint have run. Another intriguing human touch is a couple of blurred fingerprints in black ink at the hem edge. Was this an accident by the otherwise supremely careful artist who painted the shirt, or perhaps the owner, when removing the sweat-stained shirt?

The shirt is made from cotton, which was sized with starch (confirmed with an iodine test) and polished to provide a smooth surface to paint on. Dr Lucia Burgio, V&A Science Section, used XRF analysis for pigment identification. Results suggested the presence of gold, vermilion, red lead, white lead and lapis lazuli. It is made from a single centre panel painted in one piece and folded over to form the body. This and the separate sleeves are all neatly stitched together with a back stitch. The neck opening may originally have been open only part way down as there are no signs of fastenings and the lower front section is roughly cut open.

Having ascertained that it would not be inappropriate for non-Muslim conservators to treat the shirt, the next step was to plan the treatment. The shirt was lightly surface cleaned with a smooth cosmetic sponge, which removed grey soiling. The pigments were tested for water fastness and found to be exceptionally fugitive negating any further cleaning. In an early museum conservation treatment the weak and torn fold lines had been supported by stitching strips of fine silk crepeline to the reverse of the object. The crepeline was brown and crispy, suggesting that size was not removed prior to use, there was also an excessive amount of stitching holding the repairs in place: on the face the stitches were small and unobtrusive but on the reverse there was a network of overlapping threads. The textile underneath was still badly creased, it would have been impossible to relax the creases with the old repairs in place so it was decided that they should be removed in order to humidify the object, followed by the application of more sympathetic repairs. Colleagues in the Paper, Books and Paintings Section were consulted to pool expertise and suggest treatment ideas for this hybrid object, a manuscript in shirt form. Ultimately the garment formation, which restricted access to the inside of the object, influenced the treatment choice.

The water-sensitive nature of the paint dictated a cautious approach to humidification. The shirt was laid out on a wool felt pad, and covered with silicon release paper. Lightly dampened strips of blotting paper were slipped inside the shirt, these humidified the creases on both the front and back of the shirt simultaneously to minimise the humidification time. The blotters were left for approximately 15 minutes then removed and replaced with dry blotters and the area covered with Bondina® and wool felt pads to both weight the creases and absorb excess moisture. Glass weights were also used. Repeated applications gradually softened the creases.

There were two distinct types of structural damage to support. The cotton was weak along the old fold lines, some areas only had small splits but in other areas actual holes had formed (Figure 2). There were also some large losses at the lower edge of the shirt. Stitched repairs were considered too damaging, and instead tests were carried out to find a suitable adhesive support treatment. Initial suggestions to use Japanese paper repair patches adhered with wheat starch paste were discounted due to the difficulty encountered in accessing the inside of the object to remove the old stitched repairs and the extremely water sensitive nature of the pigments. It was decided a more controllable method was required and tests were carried out with Klucel™ G (hydroxylpropyl cellulose), which can be applied directly in a solvent based gel or pre-prepared patches that can be solvent reactivated in situ. A cotton fabric sized with starch was used to imitate the shirt fabric and experiments were undertaken to find a suitable support material that would also visually infill the losses.

Following tests, a 3% w/v solution of Klucel™ G cast on dyed silk crepeline was chosen. The adhesive film, which has the advantage of being lightweight and flexible, was applied to the reverse of the object along the damaged fold lines to give overall support to the weakened area. The film was solvent reactivated with Industrial Methylated Spirits (IMS), a small section at a time (Figure 3). During testing, experiments were undertaken using shaped cotton fabric patches attached to the crepeline to infill losses, however the cotton proved to be too inflexible particularly at the edges of the patch. A medium weight Japanese Sekishu paper, pre-tinted with acrylic paints was favoured instead; the patches were kept as small as possible to avoid adding bulk and watercut to give a soft feathery edge providing a much more flexible repair. The paper patches were coated with 10%w/v Klucel™ G gel in IMS and then applied to the reverse of the object on top of the crepeline. From the front, this gives the impression that the gap has been infilled with a solid woven textile. The largest area of damage spanned the side seam of the proper right edge. Two patches were cut from the adhesive coated crepeline, each with a selvedge at the side. The adhesive was removed from the outer edges of the selvedge and then the patches were back-stitched together to match the damaged area. The seam of the patch was lined up with the seam either side of the hole and the film reactivated to secure it in place. Paper patches were then applied to infill the areas of loss (Figures 4 and 5).

The shirt was supported with a Reemay® inner covered in cotton fabric to match the shirt and suspended on an acrylic former in the exhibition. This was a fascinating object to work on and an excellent opportunity to discuss different approaches and techniques with colleagues in other sections.

Further information on the Talismanic shirt can be found on The Fabric of India blog site in the post ‘A Warrior’s Magic Shirt’ by Behnaz Atighi Moghaddam. https://www.vam.ac.uk/blog/research-department/guest-post-a-warriors-magic-shirt

The Fabric of India was a temporary exhibition held at the V&A from 3rd October 2015– 10 January 2016. The exhibition was supported by Good Earth, with thanks to Experion and NIRAV MODI.