This is the second of two blog posts which discuss the 3D scanning of 25 objects in the museum’s collection as part of the wider exploration of reproductions in the digital age during the Cast Courts FuturePlan project. The first discussed why we undertook this project and its relationship to the Cast Courts, and the second will discuss the practicalities of scanning such a complicated group of objects.

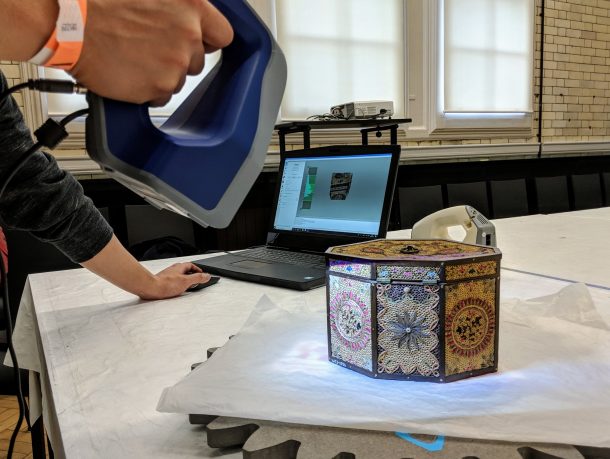

3D scanning or digitising a physical object is the process of creating a three-dimensional copy that exists purely as digital information within a specific type of computer software. This data can then be used for many digital processes including CNC milling, 3D printing, graphic rendering or even conservation. The vast majority of 3D scanning systems use light to measure the spatial position of points along the surface of an object. There are many ways this can be achieved but the most common and effective uses of light are laser, structured light and photogrammetry. For the Cast Courts scanning project we selected to use two types of handheld structured light scanners, one using white light and the other using blue light. Both of these scanners are highly portable allowing us to easily scan items of varying size on location at the museum and close to their point of display or storage.

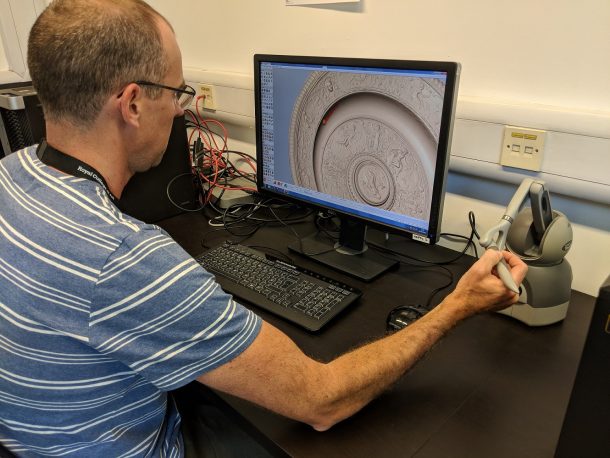

The scanners work by projecting a morié fringe interference pattern (grid of light) over the surface of an object. Cameras within the scanner measure the distortion of this pattern as it is projected over a physical surface and this is recorded as multiple points in space. Referred to as a Point Cloud, when viewed as a whole this collection of coordinates digitally recreates the original object. For the purpose of 3D printing, the point cloud is then converted to a 3D polygon mesh file called an STL.

Using light means highly accurate measurements can be taken, resulting in higher levels of detail and a truer representation of the original form. The main light source comes from a ring of LEDs and is safe to use on historical objects as well as human skin and even eyes. Once placed in a suitable position, the object can be scanned with no physical interaction whatsoever. This makes the process ideal for conservation purposes.

There are however some downsides to using light. Some of these include scanning reflective surfaces such as polished metal which can distort or bounce the light back from the object before the cameras are able to take a clear reading. Very dark surfaces will absorb some or all of the light meaning there is nothing for the camera to record. And transparent materials such as glass will allow some or all of the light to simply pass through the surface of the object so again no reading can be captured.

Light travels in a straight line from its source, to the object, and back into the camera lens. For this reason the scanner cannot see around corners. Consider a typical vase with a narrow neck. In a well-lit room the inside of the vase will remain fairly dark as the light cannot fill the inside of the vase and bounce back out into your eyes. It’s the same principle with light based scanners. If the scanner is not able to project light onto or see part of an object directly from it’s point of view, that area cannot be captured. Smart software is on hand to assist with this problem however and holes, or areas of missing data within the scan, can be automatically or manually filled using a complex hole filling command within the scanning software.

The first of the 3D models produced is now available to view on the V&A’s Sketchfab page and the original is an electrotype copy of the Temperance Basin (more widely known as the Wimbledon Women’s Singles Trophy). A new physical copy of the basin, as well as a flask were also produced for permanent display in the new gallery. The basin is made from resin and was printed from the digital scan, and a second version was made as a touch object for the label rail beneath. The flask is a plaster powder print and reproduces a silver and glass flask bought by the Museum from the Parisian firm of Froment-Meurice at the Great Exhibition in 1851. The original has highly reflective surfaces which were difficult to capture in the scan and are not reproduced in this bright blue print.

Alastair Hamer originally trained as a silversmith, specialising in the design and fabrication of cutlery and flatware. He now manages RapidformRCA and is currently helping to build in-house technical provision in the areas of Robotics, VR and Material Science, in line with the RCA’s academic vision to become a fully aligned STEAM institution.

The Royal College of Art is an internationally renowned art and design university, providing students with unrivalled opportunities to deliver art and design projects that transform the world. Running joint courses with Imperial College London and the Victoria & Albert Museum, the RCA’s approach is founded on the premise that art, design creative thinking, science, engineering and technology must all collaborate to solve today’s global challenges.

RapidformRCA is the college’s own in-house additive manufacturing and 3D Scanning department. As a central knowledge hub, we offer support and services to all students, staff, research associates and select institutions. To date, we have nine additive/3D printing machines covering six different technology sets, five different 3D scanners and a selection of specialist software for managing and processing 3D data.

Hello! Is there a reason why the electrotype of the Enderlein basin was chosen to be scanned, rather than the Briot Temperance Basin also in the V&A collection? I would be interested to know if it was because of the material difference between pewter and electroformed copper, or general condition?