The V&A has one of the world’s most important collections of Islamic pottery displayed in the Jameel Gallery and the ceramics galleries. But not everything is on show – a group of archaeological pottery fragments is kept behind the scenes in our Blythe House stores. Now that we are preparing to move its collections to the new state-of-the-art storage facilities at V&A East, the fragments will be going there too. As part of the project, I was offered the opportunity to work on a collection of over 100 pottery fragments and prepare them for their big move. The aim was to unite as many fragments as possible, to aid the understanding and cataloguing of the objects, while also providing them with better storage conditions. While doing so, I was also able to examine them carefully, assess their condition and stabilise them.

The collection is very special. It comes from various archaeological sites located in different regions in modern-day Turkey, Syria, Iran, Iraq and Uzbekistan. The museum acquired the collection between the 1890s and 1930s, donated by several well-known archaeologists and art historians who had taken part in various expeditions in the Middle East. The fragments are extremely significant, as they can tell us vital information about how the vessels were manufactured, used or traded, more than complete objects might.

According to their acquisition records the Persian pots were excavated at Rayy, which is one of the oldest cities in modern day Iran, situated in the Tehran province. In the 11th century Rayy was a capital of the Seljuk Empire and an important centre along the famous Silk Road. Rayy was destroyed in the 13th century during the Mongol invasion. The museum’s records note that the fragments found at Rayy were donated by various individuals including Henry Wallis who had bought them in 1903 for £35. Other pieces came to the Museum through Colonel Sir Robert Murdoch Smith (1835 –1900), who is key to the formation of the V&A Iranian collections. Colonel Smith was a Scottish engineer, archaeologist and a diplomat. He worked as the Director of the Persian Telegraph Company and assisted in installing a 1,200-mile-long telephone wire joining Tehran and London. He was also employed by the Department of Science and Art in the U.K. where his task was to obtain artefacts from excavations in Iran, which were later exhibited at the V&A.

Other pieces come from the city of Samarkand in South-eastern part of Uzbekistan. Samarkand is one of the oldest inhabited cities in Central Asia visited by numerous famous archaeologists. Fragments in the collection I worked on are mainly 10th century painted slipware and glazed sgraffito ware, where the design has been scratched under the glaze.

Another interesting group of pottery comes from Kish: an ancient Mesopotamian city-state located east of Babylon in what is now south-central Iraq, not far from Baghdad. The collection’s fragments were donated by Gerald Reitlinger (1900 – 1978), an art historian who in 1930 – 31 was part of an archaeological excavation at Kish financed by the Field Museum, Chicago, and in 1932 at Al-Hirah, financed by the University of Oxford. Reitlinger wrote about the pottery finds in Ars Islamica, published in 1935. He describes how many of the fragments were found in burial mounds in numerous rubbish heaps. The damp and alkaline salts had permeated all the mounds in the area eroding the glaze on some of the pottery but interestingly not all, depending on where they were positioned in the heaps. Reitlinger also mentions that some of the finer glazed pottery was found discoloured by fire, possibly because of the Mongol invasion in the area, and the burning of the Bedouin houses. This might explain the discolouration on some of the fragments. Reitlinger’s paper makes fascinating reading and his observations are particularly useful in terms of understanding the fragment’s condition.

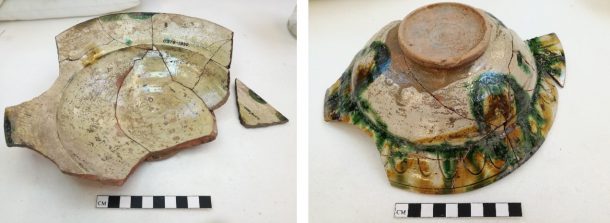

The fragments reflect different types of production in different places at different times and objects with different functions. They vary in shape, colour and design. Some are undecorated, unglazed fragments with no patterns, and others have scratched or raised designs. The latter were probably made in a mould as they have raised seamlines.

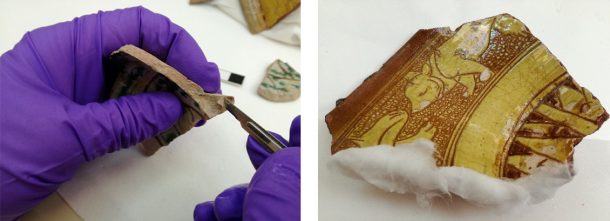

Others are glazed with a range of colours. The decorations vary from abstract designs to foliate patterns. Some of them resemble Chinese porcelain, as Islamic ceramic technology was influenced by Chinese ceramics. Many of their designs include calligraphy: words of the Qur’an (which is the central religious text of Islam) or famous works of literature.

Fragments are fully or partially glazed all around. The painted decorations are usually elegantly executed, and they have been either applied over the glaze or under, on a whitish slip, which sits on top of the clay. Sometimes the slip has been scratched or coloured.

Many of the vessels have surprisingly detailed designs on their undersides. Some of them were quite ostentatious looking vessels, and others looked as if they could have been just humble kitchen ware. What struck me was how skilfully they had all been finished.

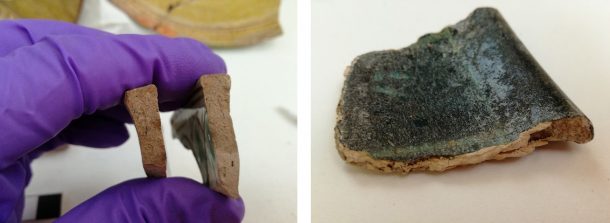

Some fragments had been assembled in the past, probably when they were first excavated or accessioned by the Museum. The break-edges had residues of plaster, animal glue, shellac, epoxy resin or glue that had become brittle, and it was apparent that some objects had been repaired on several occasions with different types of adhesive. Many of the old joins had failed over time and I was able reattach fragments to form large sections of the objects. As I began to assemble the objects, I could tell from repair material residues along the break-edges that there were missing fragments that had been there in the past. Some objects had only two or three fragments remaining, nevertheless joining them together gave a clear idea of the vessel’s original shape.

My first task was to assess whether the fragments were stable: checking the condition of the existing joins and glaze, which in some instances had lifted off. After any necessary consolidation, I would try to find a correct location for the detached fragments. Luckily, the curators had grouped the sherds in advance, so I didn’t have look very far for the missing pieces.

Once I had identified the old adhesive, it could be removed carefully, without disturbing the surrounding areas. Due to the scope of the project, I only removed adhesive from the edges that required re-bonding. Previous repair materials such as animal glue and shellac were relatively easy to remove, but others such as epoxy resin and plaster were hard to clean. The cellulose nitrate adhesive had deteriorated in time and shrunk and lifted off.

I decided to leave most of the plaster and animal glue residue in situ, as I felt that these had a more significant part in the object’s history, possibly used to attach the fragments together on the excavation sites. I applied a thin layer of adhesive as a sealant along the edges to be joined, followed by a further layer of adhesive. I had to be quick and prepared, as sometimes I would attach several fragments together at one go. I bonded the pieces together and secured them with strips of pressure-sensitive tape, which was removed once the adhesive had cured.

It was exciting to see different vessels taking shape. Working on them was fun – a little bit like building 3D jigsaw puzzles, although with many missing pieces. The objects had clearly been worked on at various times in the past and I often wondered who those people might have been. I imagined someone like Gertrude Bell sitting in the middle of a desert in her long dress, with a fragment in her hand, brushing the sand off gently. Talking about the sand, I did not attempt to clean the surfaces as most of the objects had surface deposits of sand and mud, which are part of their history.

I’m grateful that I got to spend some precious time caring for this remarkable collection of ceramics, learning a great deal about their condition and assembly. I’m thankful for my colleagues Fi Jordan, Victoria Oakley and Margot Murray in Ceramics Conservation for helping me to identify different causes of deterioration and giving me guidance on suitable materials and methods to treat the objects. I’m also grateful to Ben Hinson and other V&A Curators, who spent hours preparing and sorting the fragments prior to their treatment. I’d also like to thank Mariam Rosser-Owen for advising me on suitable material to read.