With the announcement that a new V&A site is planned for the Olympic Park in Stratford, it seems timely that I have just finished cataloguing a set of more than 400 prints and drawings relating to East London. My earlier post about a balloon flight from the Mermaid Tavern in Hackney gave a little taster of the fascinating objects I have been working on, but the entire collection can now be found online on our Search the Collections page. If you want to see anything in person, you can also make an appointment to visit our Study Room.

Our objects form part of the huge collection of John Edmund Gardner (1819-99), a lamp and chandelier maker who had a passion for the history of London and, over a period of 50 years, amassed around 50,000 prints, drawings and watercolours, plans and surveys, photographs, newspaper cuttings, trade cards and other ephemera relating to the city. He also commissioned artists to capture images of some of the buildings and streets of London, particularly those in danger of demolition.

When Gardner died the collection passed to his son, John Starkie (who, incidentally, was an art metalworker whose company made the wrought iron gates to the Henry Cole Wing of the V&A, which I walk through every morning!). John sold the entire collection to the MP Edward Coates in 1909, and it remained with him until his death in 1921, after which it was put up for auction by his executors. Coates allowed the public to access the collection, and the auction catalogue asserts that it became ‘so well known to every student of the history of London that it seems almost superfluous to attempt any description of its contents’. When it was sold there were efforts to acquire the entire Gardner collection for the nation so that it would be kept together, but unfortunately these efforts failed and sections were sold to private collections, museums and archives all over London.

The lots relating to Hackney, Hoxton, Homerton and Bethnal Green were bought by philanthropist and long-term Hackney resident Arthur Villiers, who donated them to the Bethnal Green Museum (now the Museum of Childhood, but at the time the V&A’s East London outpost). In documents relating to the acquisition, a curator recommends that the museum accept the gift, describing it as ‘of varying quality, some excellent, but much not up to exhibition standard. The whole thing, however, is full of local interest…’.

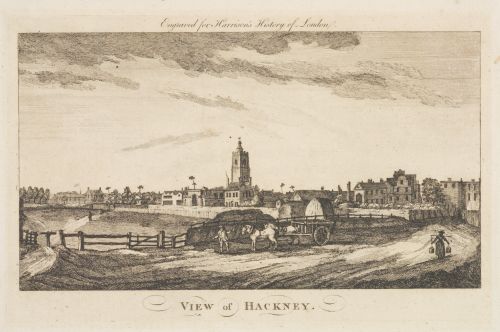

I hope that the collection will be of use to local historians as well as more generally for people interested in the changing face of London. The East End changed radically over the period covered by the collection, and most of the places depicted are completely unrecognisable today. It is fascinating to see the transition of the area from rural hamlets to Georgian terraces to densely populated urban sprawl.

The collection is so varied that I can only really give you a flavour of the sorts of objects that it contains, so I’d like to highlight a couple of my favourite themes.

The early history of Hackney

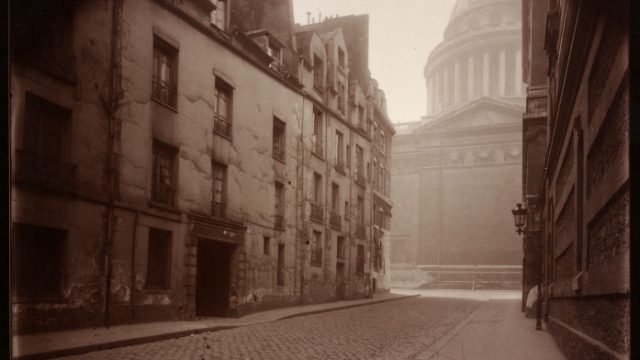

A lot of the pictures reveal Hackney’s past as a prosperous rural village, home to so many country seats that the carriages hired by visiting Londoners became known as Hackney carriages.

As most of the images are from the 18th and 19th centuries, they also show the later life of the buildings and how they were repurposed as the area became more urbanised and the population grew. The watercolour and print below show Barber’s Barn, built in 1591. It was the home of John Okey, one of the signatories of Charles I’s death warrant, and was later bought by the horticulturalist Conrad Loddiges, who used the gardens as exotic plant nurseries. Finally the house seems to have been leased to a Mr Worsley as a school (you can see the sign in the watercolour).

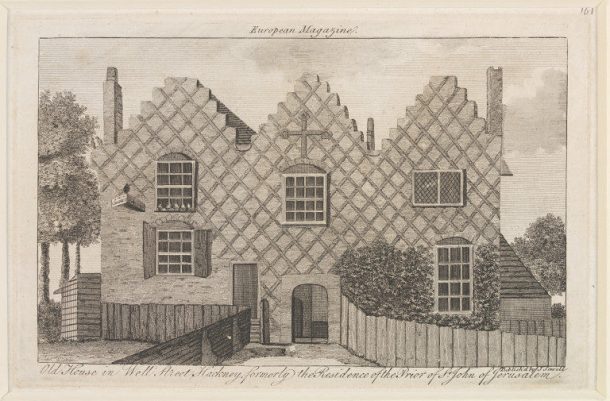

The Pilgrim’s House was built in Well Street in Hackney as early as the 1400s, and was associated with the medieval order of the Knights Hospitaller. The timber structure was later rebuilt in brick, and in the 18th century it was subdivided for poorer tenants, including chimney sweeps, whose sign is just visible on the left hand side of the building.

Sadly, very few of these grand manor houses are still standing, with the notable exception of Sutton House, built in 1535 and now owned by the National Trust. Although the frontage was modified in the Georgian period, it retains much of its original structure and interiors, including oak panelling and Tudor windows. If you want to know more, you can also use Adam Dant’s excellent online map to discover the sights of pre-industrial Hackney, and visit The National Archives’ fascinating website about Tudor Hackney.

Ephemera

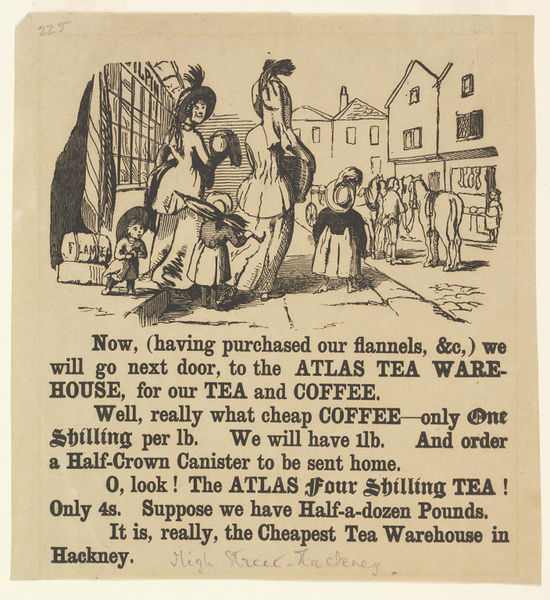

I also love the objects in the collection that tell us about the daily life of people in the East End. These range from playbills and posters for entertainment (including my personal favourite the ‘Wondrous Leotard’) to trade cards and advertisements for local businesses, and prints and cuttings from newspapers about stories as varied as the opening of Columbia Road Market, an armed robbery in a bakery and a hunt for the Hackney ghost! There is a refreshing lack of pretension in Gardner’s collecting, with everyday objects collected alongside more artistic works.

As I mentioned above, this is only a snapshot of the themes and types of objects covered by the Villiers/Gardner collection. I encourage you to explore the collection, and please feel free to contact us if you have any more information about any of the places or people featured – we’d love to hear from you!