On 6 February 1938, Ethel M Spiller, O.B.E., accepted an invitation to conduct two one-hour tours of the galleries on Easter Sunday (17 April). According to the press notice issued on 11 April, the 2.45pm tour would deal with ‘Selected Masterpieces’ and the 4pm tour with ‘English Domestic Arts in the time of Shakespeare’. The latter tour Spiller had given the previous summer and apparently it ‘rather thrilled a party of American art teachers & art supervisors’. Each tour would be limited to 25 persons.

Spiller had a longstanding and enterprising association with the V&A. When a teacher at Dulwich High School in the 1880/90s she was in the habit of bringing her elder pupils to the Museum for ‘special study’ (I suppose we’d call it a field trip these days). During World War 1 she offered her services as a museum volunteer in which capacity she pioneered holiday programmes for children with the assistance of fellow members of Art Teachers’ Guild. Using the newly opened Children’s Room as their base, Spiller and her team attempted to inspire rather than lecture the youngsters in their charge: ‘we try and make them feel it is a holiday, and that we are not teachers but ‘aunties’’ she explained to a reporter (archive ref. MA/49/2/94). For Easter Sunday 1938, however, she had been tasked with entertaining an adult audience.

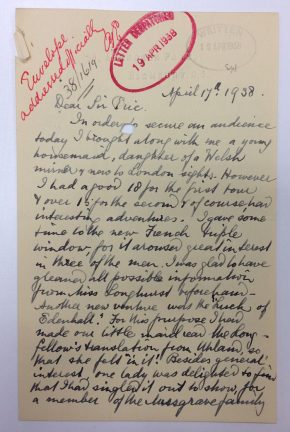

Spiller penned a short letter to Sir Eric Maclagan, the V&A’s Director, immediately following her two tours which offers us a unique and tantalising glimpse of her ‘interesting adventures’ that Sunday afternoon (archive ref. ED 84/301).

In order to guarantee at least one visitor on the 2pm tour – and perhaps as a tried and tested technique for attracting others – Spiller brought with her ‘a young housemaid, daughter of a Welsh miner & new to London sights’. She need not have worried, however, as the tours attracted decent crowds: ‘I had a good 18 for the first tour & over 15 for the second’. They were also international in their composition: ‘One visitor had just come over from New Zealand, and another a Swiss girl from the neighbourhood of Zurich’. A domestic visitor had popped up to London for the holidays and enjoyed his visit to the V&A so much that he decided to return the following day for the tour. Fortuitously, ‘nothing I showed had overlapped his experience of yesterday’.

One of the tour highlights was a recent acquisition. ‘I gave some time to the new French triple window, for it aroused great interest in three of the men’. It was fortunate that Spiller had done her homework and ‘gleaned all possible information’ from Margaret Longhurst, recently promoted to Keeper of Architecture and Sculpture, beforehand.

Another object – ‘The Luck of Edenhall’ – had been on loan to the Museum from the Musgrave family of Edenhall in Cumberland since 1926 and enjoyed a colourful backstory. According to one eighteenth-century account: ‘Tradition our only guide here, says, that a party of Fairies were drinking and making merry round a well near the Hall, called St. Cuthbert’s well; but being interrupted by the intrusion of some curious people, they were frightened, and made a hasty retreat, and left the cup in question: one of the last screaming out, If this cup should break or fall, Farewell the Luck of Edenhall’.

Spiller described this object as a ‘new venture’. She may have been referring here to her innovation of making ‘our little maid’ read aloud Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s ‘The Luck of Edenhall’ (1840), a translation of Ludwig Uhland’s ballad ‘Das Glück von Edenhall’. In this respect Spiller introduced (pioneered?) what we might describe today as an immersive gallery experience:

As the goblet ringing flies apart

Suddenly cracks the vaulted hall;

And through the rift the wild flames start;

The guests in dust are scattered all,

With the breaking Luck of Edenhall!

In storms the foe with fore and sword;

He in the night had scaled the wall,

Slain by the sword lies the youthful Lord,

But holds in his hand the crystal tall,

The shattered luck of Edenhall.

Spiller’s inclusion of this particular object on her tour was serendipitous as it turns out that ‘one lady was delighted to find that I had singled it out to show, for a member of the Musgrave family had taken her to the Museum on purpose to show it to her’. Spiller reported a further coincidence in that one of her former pupils, who knew Edenhall and the Musgrave’s housekeeper, had been ‘among my guided visitors a few years ago’.

For the 4pm tour, Spiller had another new acquisition to interest her group: ‘For Shakespearean times I had the newly acquired man’s costume’. The description is rather vague but when I asked our Curator of 17th & 18th Century Fashion, Susan North, she identified it immediately as this doublet and breeches.

Another key object on the ‘Shakespearean times’ tour was the Great Bed of Ware, which receives a name check in Twelfth Night (1601) when Sir Toby Belch describes a sheet of paper as ‘… big enough for the Bed of Ware!’

There must have been many other objects that Spiller showed to her groups; however, these four only she decided to single out for comment to Sir Eric. Her tour groups were evidently appreciative of her efforts: ‘My audience seemed happy & I always fear lest I should enjoy all the fun of it myself, buy I received many expressions of thanks’.

How did Spiller unwind after the exertions of her two tours (she was a sprightly 78 years of age)? ‘And now for the Observer X word!’