Dr. Rebecca Wade is an Assistant Curator of Sculpture at Leeds Museums and Galleries/Henry Moore Institute

The plaster reproductions of the fragmented features of Michelangelo’s David may appear strange to our eyes, but as highly portable reproductions of perhaps the most recognised sculpture of the Italian renaissance they occupy an important place in the history of art and design education.

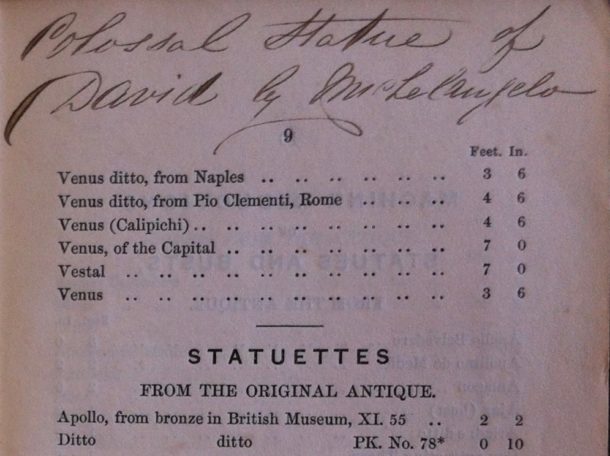

It is difficult to know exactly when the Brucciani firm began to make and sell these objects, although clues emerge in the catalogues held in the National Art Library. In the Catalogue of Casts for sale by D. Brucciani published before 1860, we find under the category ‘Miscellaneous Casts, Studies for Schools, Artists, &c.’ are listed ‘Sections of the Face, Ears, &c., taken from antique and modern statues’. It is not clear whether or not they included those taken from David, although the catalogue is annotated by hand on page nine with ‘Colossal Statue of David by Michelangelo’ which suggests that a full-size plaster cast was available [Figure 1]. Could it be possible that Brucciani had access to the plaster cast of David installed at the South Kensington Museum in 1857?

The next catalogue was published in 1864 to mark the opening of Brucciani’s expanded premises: the ‘Galleria delle Belle Arti’. It lists David as available for purchase as a reproduction ten feet tall—some seven feet shorter than the marble sculpture from which it was derived, though still one of the largest casts listed in the catalogue at the time. Brucciani offered ‘machine reductions’ of a number of canonical sculptures, so it is possible that David was scaled down to a more manageable size in this way too.

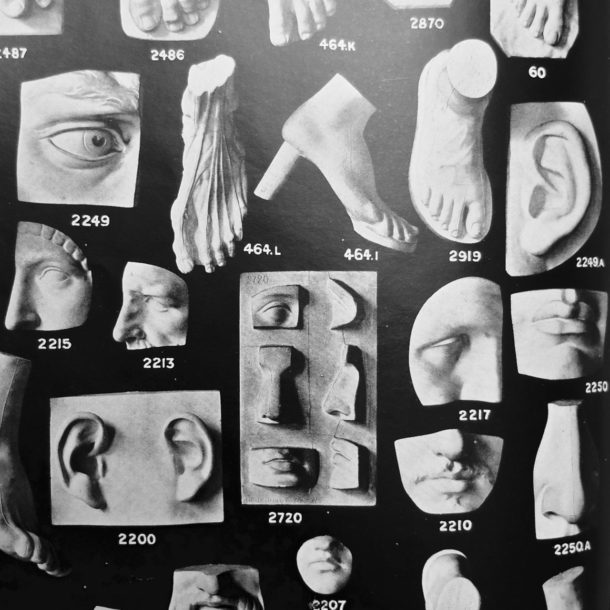

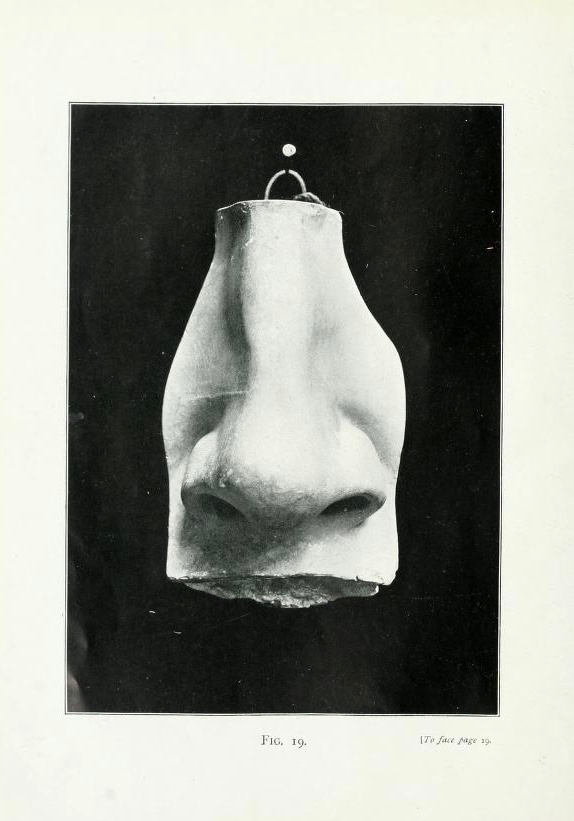

It was not until the publication of the 1889 catalogue that the separate components of the head of David were listed, though by this point Domenico Brucciani had been dead for nine years and the business operated under new management. Both eyes, the mouth and nose were available to buy for two shillings and sixpence each and for four shillings, you could purchase a plaster slab with an eye, nose and mouth embedded into it, with both front and side profiles. This catalogue was oriented towards schools operating under the curriculum of the Department of Science and Art and perhaps for this reason, the full statue of David was withdrawn from the list. The 1906 catalogue was also intended for the educational market and added both ears to the selection above, will illustrations provided for the first time [Figure 2]. The full figure reemerged in this catalogue at a cost of £100—four times more expensive than the next most costly cast (a group from the Laocoön) perhaps indicating that it was offered at 1:1 scale.

The importance of the components of the face of David for art and design education was cemented by the French émigré sculptor Édouard Lantéri (1848-1917). Lantéri taught at the National Art Training School in South Kensington between 1880 and 1910 after moving to Britain to work for the sculptor Joseph Edgar Boehm in 1872. In 1902—one year after having become the first Professor of Modelling at what had by then been renamed the Royal College of Art—he published the first of three highly influential volumes of Modelling: A Guide for Teachers and Students. Modelling in clay towards casting in plaster and bronze remained the dominant form of sculptural instruction and Lantéri’s illustrated text described the cumulative stages of production from the correct tools to the completion of a full figurative sculpture modelled from life.

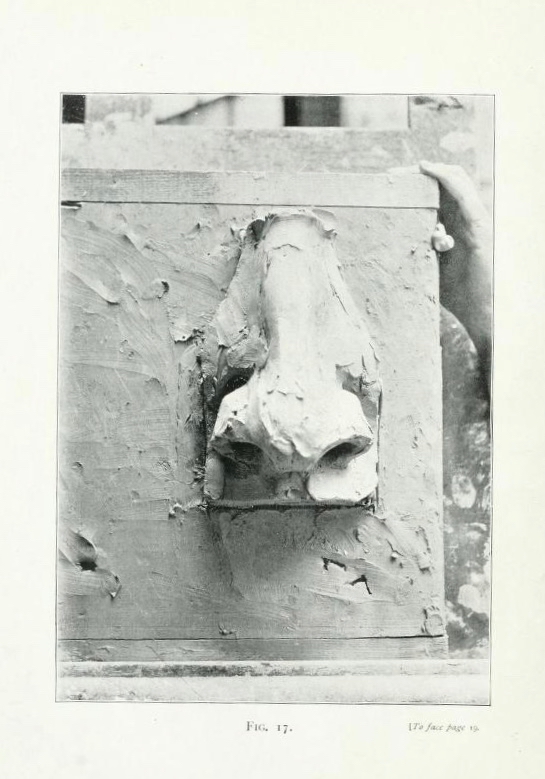

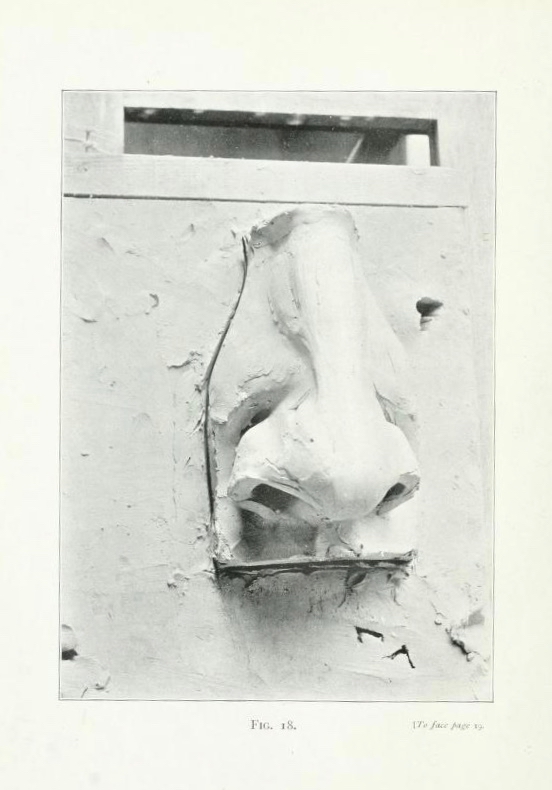

Before the student began to model from life, Lantéri advocated the use of casts taken from the face of David for students to copy in clay, beginning with the mouth and working through the nose, ear and eye. He wrote that these forms ‘are executed with such precision, so much knowledge of form and anatomy, that in copying them the student is seized with the desire to know the reason for these forms, and he is thus urged on to the study of Anatomy, so necessary for sculpture’. This practice conformed both with the tradition of academic training and the National Course of Instruction—otherwise known as the South Kensington System—instigated by Henry Cole and Richard Redgrave via the Department of Science and Art in 1852. In this mode of education plaster casts were not sharply differentiated from the objects from which the moulds were taken; the reproduction was thought to communicate the lessons embedded in the form just as well as the original. Each element of the face was illustrated from the rough sketch in clay through a process of refinement and smoothing out, culminating in as accurate a clay reproduction of the plaster reproduction as possible. [Figures 3 to 5]

Moving from the part to the whole, Lantéri continued to advise the student to consider David as an object lesson in figurative sculpture. That the head and its constituent parts were considered to be both distinctive and unified was noted by Lantéri: ‘Take, for instance, a cast of the head of Michel-Angelo’s David; let it be placed in any light whatever,—this head always retains its resemblance, and nothing seems to have been left to chance, the whole remains neat and clear; the planes retain the required direction, and, modelled well together, they give movement to the whole surface’.

In the second half of the nineteenth century the plaster casts of the nose, mouth, eyes and ears of Michelangelo’s David were used to train students to think in three dimensions, working from the isolated component to the face, the bust, and on to the whole human figure as the foundation of artistic practice. Instead of working from the inside of the body outwards, David was thought to lead students toward correct proportion through the anatomical information visible on the surface and stimulate curiosity about the underlying structures of the body. Now generally consigned to decorative objects, these casts reveal much about the cultural priorities of Victorian Britain.

REBECCA WADE

Dr Rebecca Wade is an art historian and assistant curator of sculpture at Leeds Museums and Galleries, based at the Henry Moore Institute. Rebecca’s research interests lie in the relationships between museum and exhibitionary cultures, art education and teaching collections in the second half of the nineteenth century. She has completed postdoctoral research projects on plaster casts at the Museum of Classical Archaeology (University of Cambridge Museums), the Henry Moore Institute and the Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art. She is coeditor of the recently published volume Art versus Industry? Visual and Industrial Cultures in Nineteenth-Century Britain (Manchester University Press, 2016) and her research monograph, Domenico Brucciani and the Formatori of Nineteenth-Century Britain, will be published by Bloomsbury Academic in 2018.

In the next post, Kurt van der Basch, a freelance storyboard artist for films including Star Wars: The Force Awakens, Cloud Atlas, and Jurassic World: Fallen Kingdom, will describe his experience in drawing a cast of David’s nose. Stay tuned for Echoes of Michelangelo – Personal Observations on Drawing David’s Nose.

I just want to say thanks to the one who recommended the website; it’s been very helpful to me. And now and I’m happy.

good to get hack for gta games,