by Cerys Fry, Paintings Conservator

Preparing to move the Victoria and Albert Museum’s collections from Blythe House to the new Collection and Research Centre is a mammoth project. The collections include over 250,000 objects, 350,000 library books and 1000 archives. Belonging to this treasure trove of art is a collection of 1600 paintings, which were surveyed to evaluate which needed intervention before the move. The survey showed that around 10% needed some attention to make them safe to move. This preparatory work was started by Carolina Jiménez Gray in November 2018 and in November 2019, the author continued with the project.

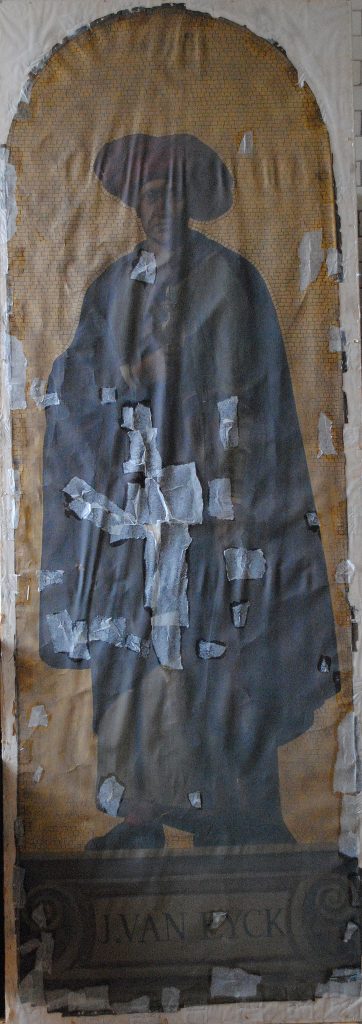

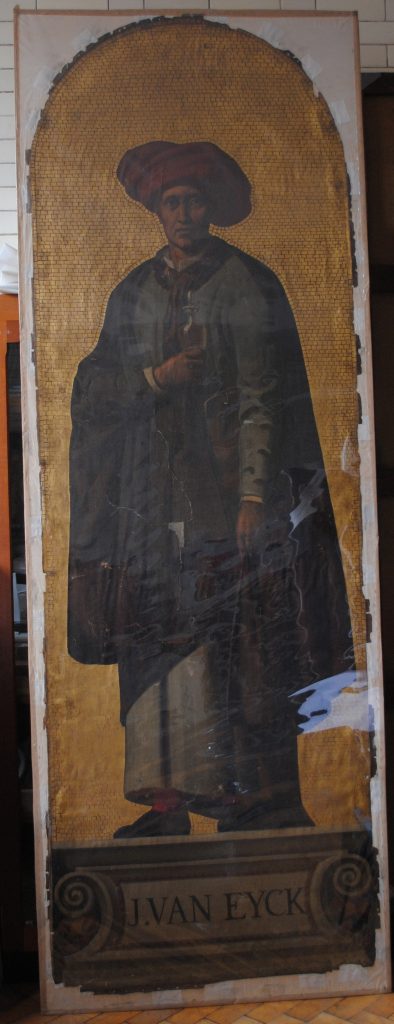

A collection of oil on canvas paintings, commissioned between 1862 and 1871 and made as full-scale designs for the ‘Kensington Valhalla’ mosaics, are a case in point. Most of the paintings were in storage at Blythe House and several of the canvases had deteriorated and were in poor condition. There was a marked difference between those that were framed and glazed to those left unprotected on both front and back. In many cases, the unlined canvas had become so acidic and brittle that the tacking margins had split along the fold-line, or large tears had formed.

Soon described as the Kensington Valhalla in The Builder magazine1, thirty-five full-length ‘portraits’ in mosaic of European artists, architects and sculptors gradually replaced the paintings in the arcade niches that ran around the upper level of the South Court of the South Kensington Museum, as the V&A was then known. The mosaics figuratively placed titans of the applied and fine arts in the resting place of the heroes of Norse mythology, or literally at the top of the walls of the South Court. The selection of artists reflected the desire to honour the established canon and also those belonging to the Arts and Crafts movement. Their connection sought to show the importance of both fine art and applied arts, a principle that has always been important at the V&A. Artists and subjects were matched if possible; for example the artist Frederic, Lord Leighton (1830-1896) was commissioned to paint Cimabue (1240-1302), who was the subject of his first major work ‘Cimabue’s Madonna carried through Florence’, shown at the Royal Academy of Arts in 1855. The Cimabue mosaic is missing, giving the design (1140-1868) an added importance as a record of what has been lost. A few mosaics can still be seen in the Museum at the entrance to the exhibition courts and opposite the entrance to the upper level of the British Galleries but most are in storage at Blythe House and also being prepared for the decant.

Conservation treatments that were carried out on the paintings included:

- Removing a thick layer of dirt from the reverse and front of the canvas

- Removing debris stuck between the stretcher bar and canvas

- Removing old facings

- Reducing planar deformations

- Re-enforcing tacking margins

- Making inserts for large losses in the canvas

- Tear mending

- Stretcher bar linings

Many of the canvases had no backboards and a thick layer of dirt had built up on the front and reverse. The exposure to the dirt on the reverse had allowed it to be drawn into the canvas fibres, creating acidic conditions. The acidity had made the canvas fibres incredibly brittle and many of the paintings had large tears as well as planar deformations (Figures 1 and 2). In many cases the tacking margins had split and the painting had begun to lift away from the stretcher bar. Many of the paintings had been faced with a water-soluble adhesive to try and protect the canvas from tearing further. In some cases, this facing had created areas of tension surrounding the damage and was causing new tears.

Due to time constraints, it was not possible to carry out treatments such as lining. Instead, paper conservation materials were employed. Using wheat starch paste and Japanese kozo tissue, small tissue tabs were made to reinforce areas where the tacking margins had failed (Figure 3). Where a little more strength was needed to reinforce splits and tears in the turnover edge, nylon gossamer and Beva film was used. In some instances, it was necessary to repair tears. After the planar deformations had been reduced, the canvas fibres were realigned and rejoined using Lascaux Polyamide Textile Welding Powder, which is a hot-melt adhesive made from thermoplastic copolyamide resin. The use of this material gave the canvas fibres a little more integral strength.

These canvases were very vulnerable due to their size and the fact that the fabric was so brittle. Each time they were moved (no matter how carefully) there was a lot of movement to the painting. For this reason, stretcher bar linings of polyester sailcloth, or occasionally Tyvek, were fed under the stretcher bars and stapled to the reverse of the stretchers to try and reduce this movement during handling and transport (Figure 4). They also serve to keep the reverse clean. A stretcher bar lining works by creating an air dam between the fabric and the original canvas; this dampens vibration at the centre of the painting by raising the natural frequency of the canvas to four times its original frequency. This means that when the paintings are transported to the new Collections and Research Centre in Stratford, the canvases will be out of the frequency range output of transit vehicles.

It was satisfying to be able to work on these paintings at a time which coincided with the treatment of the Valhalla mosaics by sculpture conservators Adriana Miró and Sayuri Morio. The sheer size and condition of the paintings and mosaics meant careful planning of all the object moves was essential. The work of the Decant Technical Team, led by Amel Earle, underpinned all our preparations, which included three separate aspects: the treatment of the paintings; the treatment of the mosaics; and designing a futureproof method for the transport and future examination of the mosaics. We hope that the mosaics will one day be reinstated in the South Court.

References

- Julius Bryant, Designing the V&A, London, 2017, p.95

Further reading

An innovative storage and transport solution for the Kensington Valhalla • V&A Blog (vam.ac.uk)