In 1863 a British antiquarian and architectural historian named John Henry Parker (1806-1884) contracted rheumatic fever. His doctor advised him to spend his winters somewhere warmer than Britain, for the sake of his health. Parker settled on Rome and, beginning in 1864/5, spent the next 13 winters there. But rather than taking the chance to relax, he instead began an ambitious project to create a record of the classical and medieval sites, monuments and artefacts of Rome, using the relatively new medium of photography. Parker was not himself a photographer, but commissioned others to take the photographs under his direction. Years of work eventually resulted in his 13-volume work ‘The Archaeology of Rome’ in which his text was illustrated by over 3300 photographs, providing an invaluable record of the state of Rome and its monuments in the late 1800s. Unfortunately, a fire destroyed most of Parker’s negatives in the 1890s, but sets of prints remain, including a large collection in the Victoria and Albert Museum. In this post I will give an overview of Parker’s project, the photographs and their legacy.

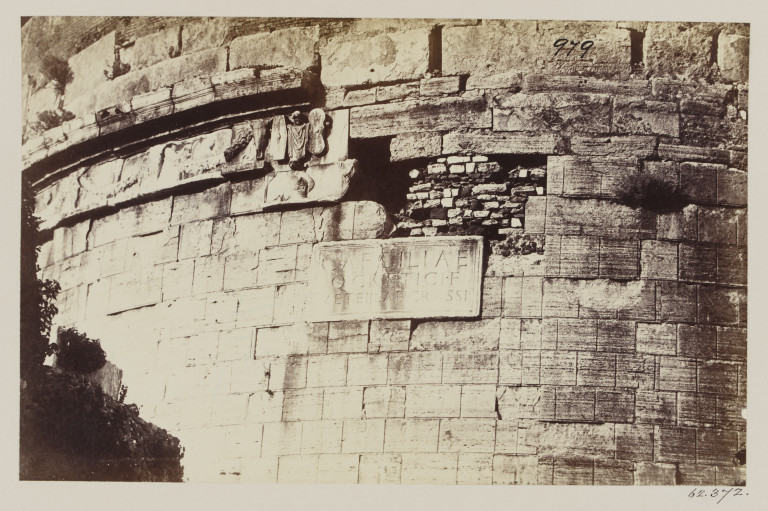

Parker was following in a long tradition of recording Rome, but previous representations had been limited to paintings, drawings and engravings. Parker believed that while these reproductions were useful to an extent, to produce a truly accurate record only photography would do. His aims were less artistic than scholarly: he planned to use close observation of architecture and construction methods to accurately date walls and buildings, providing support to his belief in the legends of early Rome. In the introduction to his 1867 catalogue he explains his thinking: ‘The sort of minute accuracy which such a work requires could only be obtained by means of Photographs. No artist ever thinks of drawing the joints of masonry, the width of mortar between bricks, yet these are the very points which sometimes are the best guide to the age of a building.’

Who took the photographs?

Parker was not a photographer himself, so in order to capture these images he hired local photographers, and is known to have worked with six Italian photographers over his fifteen-year project: Adriano De Bonis, Giovanni Battista Colamedici, Filippo Lais, Francesco Sidoli, Carlo Baldassare Simelli and Filippo Spino. They are named in his catalogues but not identified with particular photographs, although we know that Simelli is responsible for many of the earliest images in the series.

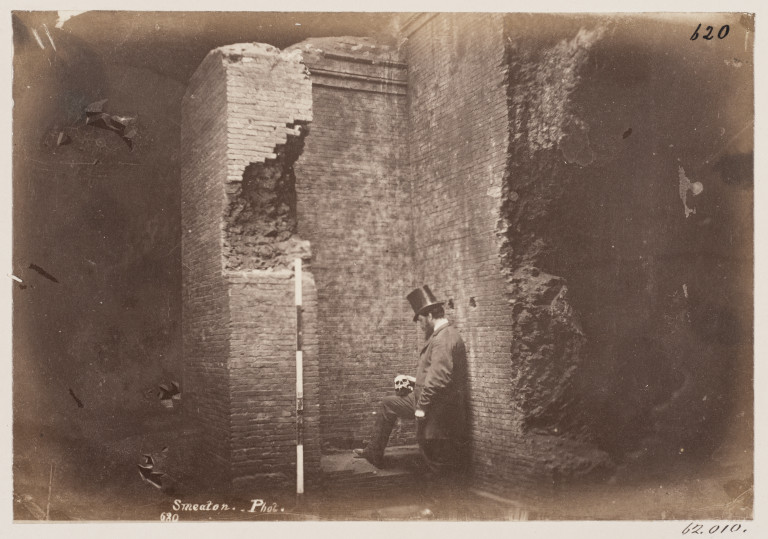

While Parker was back in London in the summer of 1866 he met a young Canadian photographer, Charles Smeaton, who was familiar with a new method of flash photography which used a magnesium flare to create a bright light. Parker convinced the Canadian to accompany him to Rome, where Smeaton was able to capture the first images of Roman and Christian catacombs, illuminating dark spaces which had previously been almost impossible to photograph. As some catacombs have become inaccessible due to rising water, and wall paintings have faded once exposed to light, some of these images now provide our only record of these underground treasures.

What did they photograph?

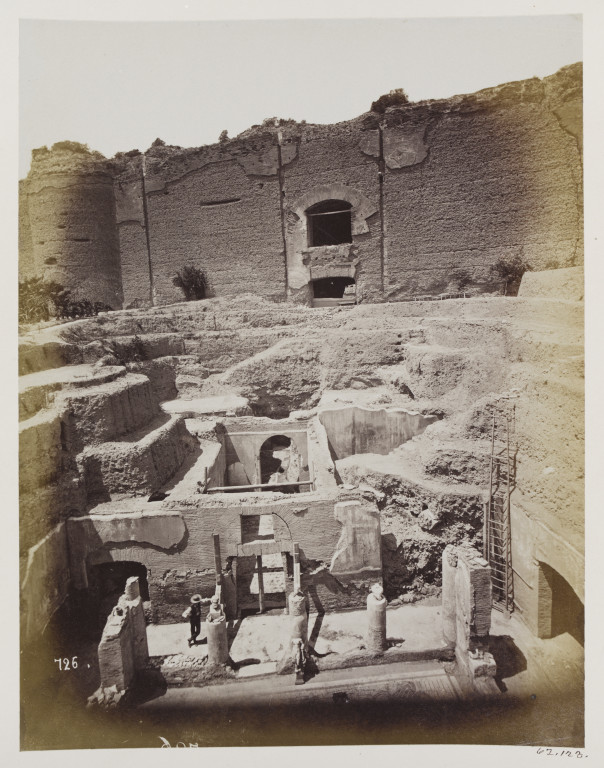

Rome in the mid-19th century was a dynamic and rapidly changing city: expansion, industrialisation and flood protection in the city opened up new excavations, and politicians sought to enhance the prestige of the new capital by uncovering and publicising its illustrious past. As more of the ancient fabric of Rome was uncovered, this was a perfect time for Parker to capture sites and artefacts as they emerged. He was a founding member of the British Archaeological School at Rome and had connections with archaeologists which allowed him privileged access to excavations.

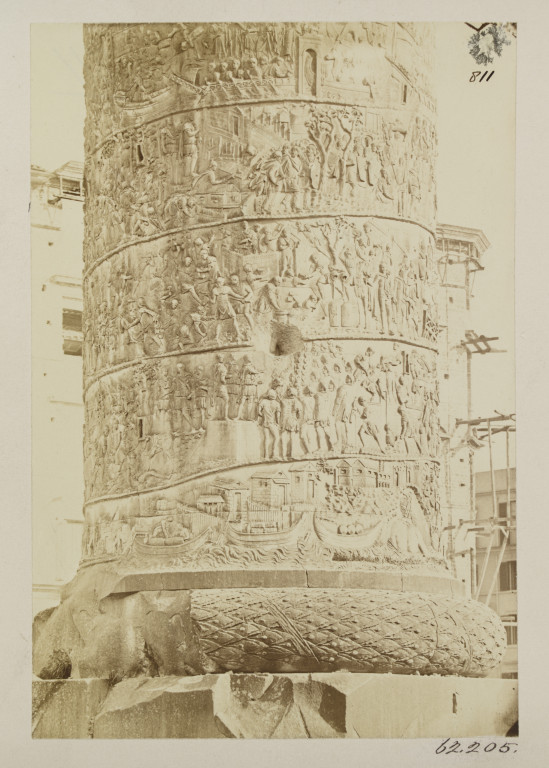

Photographs in the collection also depict aqueducts, sculpture, mosaic, inscriptions, and objects in museums and churches. Although Parker’s main focus was ancient history he also recorded a number of medieval buildings.

Some of the most significant images for historians show buildings or monuments which no longer exist. The image below shows a medieval paved street covering the Forum of Augustus, with only the top half of the columns and arch visible. This street, along with 20 feet of earth below, has since been removed and the later buildings destroyed in order to uncover the forum. Other images show details of Roman structures which have since been demolished, such as the Arch of Honorius which survived only a few years after the photograph was taken, or which have suffered from the effects of weather and pollution, such as Trajan’s Column. Many of the photographs are also valuable in giving us a snapshot of 19th century Rome before the developments of the 20th century.

As well as using the photographs for scholarship, Parker also took advantage of the relative ease of reproduction to allow his work to reach a wider audience, as well as making some money. Parker sold prints of his photographs both in Rome (winter) and London (summer), making his new photographs available every season. He produced catalogues to advertise them – the first was published in 1867 and covered the winters of 1864, 65 and 66. It contained details of 755 photographs. By the end of the project there were almost 3400 photos available.

The South Kensington Museum (now V&A) purchased sets of photographs in 1868, 1869 and 1870, around 1900 prints in total. Each one has a series number which can be looked up in Parker’s catalogues so they can be identified, and I am currently working to add this information to our online catalogue.

I wanted to finish with a few of the quirkier photographs from the series, including an unusual composition of skulls and tiles, and a view of the Tiber which includes a ghostly image of the photographer’s camera. If you want to see more of Parker’s images you can use Search the Collections online, or visit the Prints and Drawings Study Room.

Buongiorno,

con molto piacere sto consultando il Vostro polo museale particolarmente ricco di opere d’arte di ogni genere.

Sono di Roma, amante della storia antica e di quella del XIX° secolo sulle trasformazioni avvenute a Roma che tanto abilmente ha fatto fotografare il Sig. Parker.

Sarei grato di avere qualche link per la consultazione on line dell’archivio fotografico di Parker.

Di nuovo tanti complimenti dall’Italia per il Vostro prezioso lavoro.

Paolo Francesco Buongiorno

Via Fiore, n. 9

San Vito al Tagliamento – Pordenone

Cellulare 3389649263

Casa 0434876325