If you’ve ever wandered the corridors of the V&A, you’ve probably come across the dazzling Sacred Silver and Stained Glass gallery (if not, I definitely recommend a visit!). This is one of my favourite rooms in the museum, both for the beautiful effects produced by the changing light at different times of day and year, and for the chance to get a close-up view of the amazingly detailed glass painting, something which often can’t be appreciated when seen high up in a window.

You may be wondering what this has to do with prints and drawings, let alone the Factory Project. Well, I have recently discovered that the museum has a wonderful collection of designs, cartoons and drawings of stained glass. While these can never replicate the effects of light shining through real glass, they can help us appreciate the draughtsmanship and skill needed to produce a stained glass window, and reveal some of the processes involved in translating a design from paper onto glass. Many of the drawings are also works of art in their own right.

For the first in a short series of blog posts, I am going to explore Medieval and Renaissance designs, with further posts on 19th-century designs and drawings of existing glass.

Stained glass began to be widely used in the 12th century, and the basic processes have changed very little since then. Small, irregularly shaped pieces of glass, known as quarries, were cut to shape using a pattern or cartoon. They were then assembled using the cartoon as a guide and held in place with strips of lead, before details were painted on with a fine brush. The designer therefore used the cartoon to indicate the colours of glass to be used, the lead lines, and the details for the glass painters to copy or trace.

In the early medieval period, when paper was expensive and scarce, the cartoon was drawn on a chalk-covered board or table, so that the board could be wiped and reused. Later, paper began to be used so that all or part of the design could be used in another window, but sadly very few of these designs have survived. The video below shows the process of making a medieval stained glass window, reproducing one of the panels in the V&A’s collection.

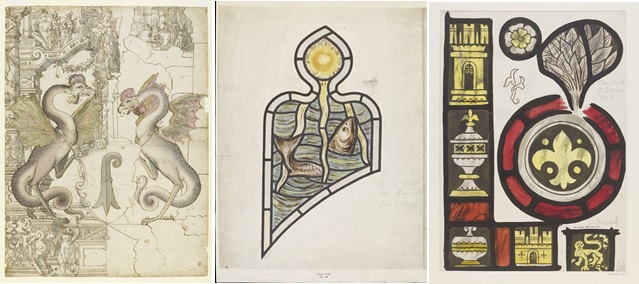

The earliest designs in the V&A’s collections come from the 15th and 16th centuries, particularly from Germany and Switzerland. Many of the major painters and printmakers of the time also designed stained glass, and although these designs are often overlooked among the artists’ other works, I think they’re really beautiful, with fluid lines and intricate detail.

In fact, when I first looked at them I didn’t believe that something so detailed could be translated onto glass. However, in these windows there was less reliance on leading to define the shapes in the design, with larger quarries and more painted detail used instead. This allowed the artists more space to work with, and scope for more elaborate designs.

Renaissance draughtsmen used painting and drawing techniques to design the window, working on both the overall layout and individual details and figures. Usually they did not execute the glass painting themselves. Instead they worked closely with extremely talented but often unsung glass painters, who had the difficult task of translating a drawing into the medium of glass.

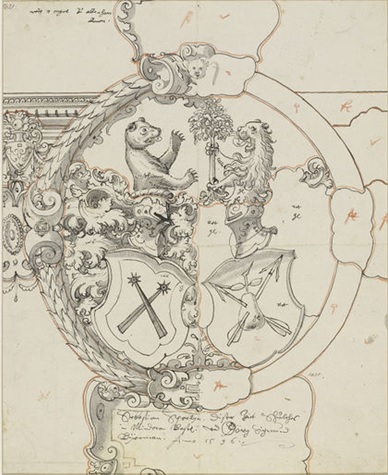

Here we can see the drawing clearly marked out, showing the different quarries of glass, what colours should be used, and where the leading will go.

This drawing gives us a lot of information about the design process of stained glass. The architectural elements and the figures appear to have been drawn by two different hands, and it is likely that a draughtsman in the workshop filled in the basic outline of the panel, and then left notes to Baldung instructing him to fill in the more complicated figures of the nuns.

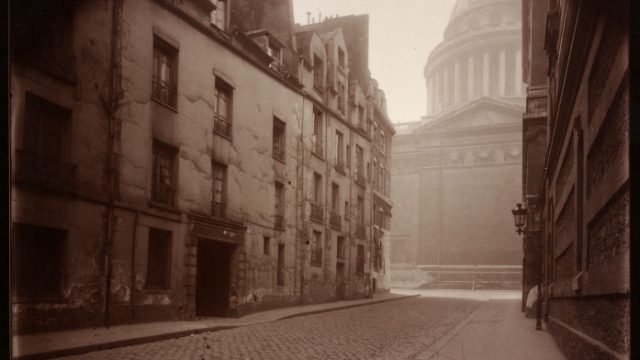

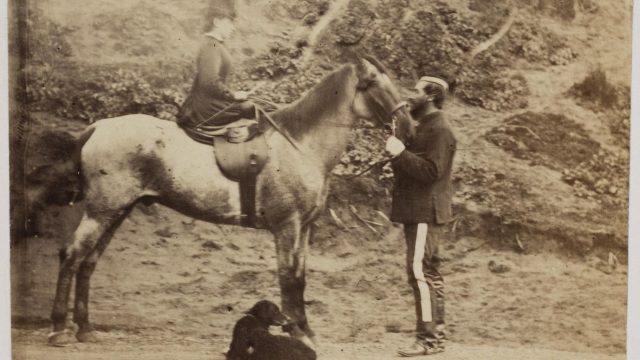

Finally, the drawing above is an example of a stock design from a stained glass workshop, which the customer could then personalise with modifications including their own coat of arms or design on the shield. There are also chalk lines around the woman’s headdress, which may show an alternative form for the customer to choose. The period saw a rise in secular stained glass, and the panel made from this design would probably have been placed in the window of a town or guild hall, along with other panels displaying the arms of prominent citizens.

What makes these drawings particularly valuable is the fact that many of them provide the only evidence for Renaissance glass. For example, the window based on the Hans Baldung drawing above was destroyed later in the 16th century, possibly during a peasants’ revolt. In Britain, many medieval and Renaissance windows were smashed during the Reformation in the 16th century and under Cromwell in the mid 17th century, and the traditional ways of working with stained glass died out. Look out for my next post, in which I will be looking at how the art form was revived in the 19th century.

Hello,

A colleague and I are trying to recreate a window from Sainte-Chapelle and have a question about the cartoon. She has recreated a lime wash board but is having trouble with her charcoal smudging. Is there evidence of something being used over the charcoal lines or replacing the charcoal once the lines are set precisely where the glass needs to be scored? I know modern artist use hairspray to keep charcoal from smudging. However, we are trying to find a more period correct method. Thank you for your help.

Sincerely,

Bobbie Jo Nelson

Dear Bobbie Jo,

Thanks so much for reading my post and for your question.

As almost all the original cartoon boards have been lost, most of what we know about how Medieval stained glass was made is from a work by a 12th century monk known as Theophilus, ‘Di Diversis Artibus’ (‘On Diverse Arts’). He gives quite detailed instructions on how to prepare the board and transfer the design to the glass, so this might be helpful to you and your colleague. There is a translation online at: http://books.google.co.uk/books?id=wo4EAAAAYAAJ&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false, and the relevant section is Chapter XVII ‘Of Composing Windows’ on p. 137.

You might also want to try contacting the Stained Glass Museum in Ely (http://stainedglassmuseum.com/).

Good luck with your project!

Best wishes,

Sarah