by Lucia Burgio, Senior Scientist (Object Analysis) and Dana Melchar, Senior Furniture Conservator

In 2015, a seventeenth-century South American barniz de Pasto table cabinet (W.5-2015) entered the Victoria and Albert Museum’s collection. While mainly European in form and design motifs, it is made from mopa mopa, a resin derived from a native South American plant, and at the time was believed to be the first object of its kind in a public collection in the UK (we have since discovered that we have three mopa mopa flasks decorated using the same technique).1 Because of its uniqueness, the object underwent extensive technical examination and scientific analysis by the V&A scientists, while at the same time being studied by our curators, and examined, investigated and treated by our conservators (Figure 1).

Excitingly, the relatively routine scientific analysis sequence revealed unexpected facts. These results have led us to reconsider barniz de Pasto objects under a new light as far as materials and techniques are concerned.

In the first instance, X-ray fluorescence (XRF) was used for non-destructive analysis of pigments on the surface of the cabinet. While the most common historic white pigment is made from lead, our tests showed that calomel, mercury(I) chloride, Hg2Cl2, was the white pigment used throughout the object. In the past, calomel has been detected on paintings as a degradation product of the red pigment vermilion, mercury(II) sulfide, but had never been identified as a pigment in its own right. The only place where calomel was not detected on the surface was the inside of the lid. Analysis confirmed the visible decoration in this area was painted using a selection of modern materials, very different from those used on the rest of the object.

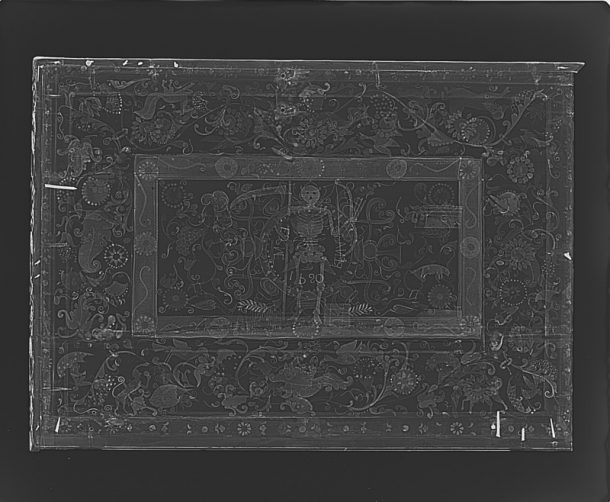

X-radiography of the object’s lid revealed an underlying dramatic scene, currently hidden by modern over-paint (Figure 2). This scene was difficult to decipher due to the overlap of the designs from the outer and the inner surfaces of the lid in the X-ray.

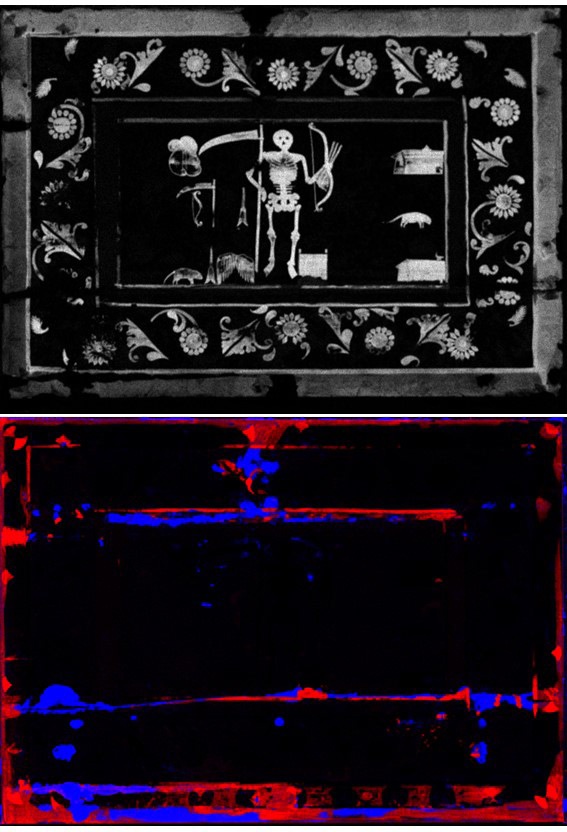

Micro computed tomography (µCT) of the lid at the Natural History museum enabled us to visualise the hidden scheme alone: a skeleton with a scythe and a bow stands proud in the centre of the lid, surrounded by small animals and other items, the significance and symbolism of which is currently being investigated (Figure 3).

Additional tests were carried out at the National Gallery, London, where the chemical elements on the lid were visualised using mapping X-ray fluorescence (MA-XRF). This procedure allowed us to verify the extent of the use of calomel on both the outer and inner surface of the lid, and confirmed that this ‘mercury white’ had been the only white pigment used throughout the cabinet in the original scheme (top of Figure 4).

The same technique was used to map elements such as lead and calcium. The presence of lead in a few small areas of white retouching was linked to the use of lead white to repair the original mercury white decoration where the latter had been lost or damaged. In contrast, calcium was detected where structural damage had occurred and infills had been applied (for example to repair cracks or plug old nail holes) (bottom of Figure 4).2,3

For more details about the barniz de Pasto table cabinet, and the discovery and characterisation of mercury white, please see the three articles listed under References.

Acknowledgments

This research was generously supported by Jorge Welsh Works of Art, London and Lisbon. The authors are also grateful to Nick Humphrey, V&A Curator, Furniture Department, for the collaborative exchange of ideas on the cabinet; to Paul Robins, Radiographic Protection Officer, V&A Photographic Studio; to Brenda Keneghan, Polymer Scientist, V&A Science Section; Stanislav Strekopytov, Jens Najorka, Tomasz Goral, Amin Garbout, Brett L. Clark, from the Natural History Museum; and David A. Peggie and Marta Melchiorre Di Crescenzo, the National Gallery London, for their assistance with the MA-XRF.

References

- https://www.vam.ac.uk/articles/box-of-mysteries [accessed 8 October 2018]

- https://www.vam.ac.uk/blog/caring-for-our-collections/hidden-surprises [accessed 8 October 2018]

- Burgio L., Melchar D., Strekopytov S., Peggie D.A., Melchiorre Di Crescenzo M., Keneghan B., Najorka J., Goral T., Garbout A., Clark B.L.; Identification, characterisation and mapping of calomel as ‘mercury white’ a previously undocumented pigment from South America, and its use on a barniz de Pasto cabinet at the Victoria and Albert Museum, (2018) Microchemical Journal, 143, pp. 220-227

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0026265X18307471

Given by Dr Robert MacLeod Coupe and Heather Coupe in memory of their brother, Philip MacLeod Coupe.