In the V&A Archive, we hold a range of files relating to the history of the museum, including ‘nominal files’ that contain correspondence between the V&A and a named person or organisation. Recently, while hunting for a file for one of our readers, my eye fell onto the title ‘Universal Races Congress Exhibition’. Immediately intrigued, I decided to investigate further. Previously, we hosted a group of volunteers from the Look We Here: Curating the Caribbean project, who were in the early stages of planning a display.

In preparation, we looked into our files for evidence of the V&A’s links with the Caribbean. This led me to some interesting questions about the V&A’s role in the British Empire – and so I was curious to see what kind of involvement the museum had with a congress on race in the early 20th century.

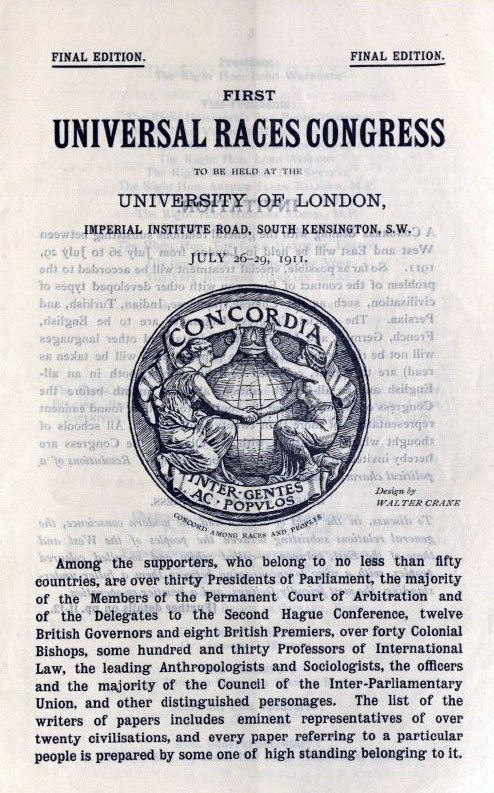

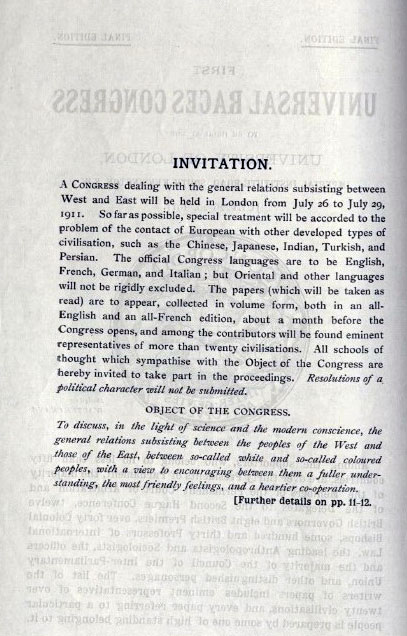

The First Universal Races Congress was held at the University of London from 26 to 29 July 1911. The focus of the event was to discuss the relations between races, and between the East and West more generally, ‘with a view to encouraging between them a fuller understanding, the most friendly feelings, and a heartier co-operation’ (Universal Races Congress Exhibition, archive ref. MA/1/U67). To this end, representatives from various administrations attended, and speakers included historian and sociologist W.E.B. Du Bois, anthropologist Franz Boas, and many others. At first it might appear curious that the organisers of such an event would have been in correspondence with the V&A, but the conversation was in the context of plans for an accompanying photographic exhibition.

On 27 June 1911, Gustav Spiller, the organiser, wrote to the museum, outlining his plans to include ‘charts, photographs, books and periodicals which have a bearing on Inter-racial Problems’ in the exhibition. Spiller asked to borrow any works which the museum had published, which are on the bibliography on ‘Racial Questions’ he attached (but the bibliography unfortunately no longer survives in the file). The only book to fit the bill was published around 30 years earlier, The Industrial Arts of India by George Birdwood (1884), which was ultimately contributed. The book is part of a series of Science and Art Handbooks, published for the Committee of Council on Education (which had authority for the museum, at that time known as the South Kensington Museum). The focus of part 1 of the book was the Hindu Pantheon, while part 2 centred on ‘the Master Handicrafts of India’ and was a reprint of part of Birdwood’s Handbook to the Indian Court at the 1878 Paris International Exhibition.

The Industrial Arts of India uses the subject of Indian art to explore issues of race, national histories and ‘civilisation’

The Industrial Arts of India uses the subject of Indian art to explore issues of race, national histories and ‘civilisation’ with Birdwood providing his analysis of the social and political history of India and its neighbours. Similarly, in his introduction to the Handbook to the Indian Court, Birdwood discusses his views on the development of civilisation. These include the view that due to its coastline and resultant unapproachability, Africa’s

tribes and nations still remain in their primitive state of savagery, or have advanced only to barbarism […] and though the civilisation of Asia is far before that of Africa, it has never advanced beyond its semi-civilised as distinguished from barbarous stage, while Central Asia still remains barbarous (pages 1–2).

He goes on to place the history of India within the context of the rise and fall of empires and nations. One sentence that seems to sum up his view of the development of civilisations is that all humans developed from one race, which diversified and ‘reached at last its highest intellectual development in the Semitic and Aryan races’, and later

everywhere the keen, bright, energetic Aryan race excited the other races to a higher civilisation, and only the civilisations in which the Aryan element is pure or predominant have proved progressive (page 5).

These books at first appear to be about Indian art, but reveal themselves to be wider commentaries on humanity, which illuminate the deep-rooted Victorian ideologies of race and empire, and encourage a hierarchy of civilised and uncivilised peoples. Even a book that is nominally a guide to one section of an exhibition delves deeply into racist ideas about the shape of the world – and this in turns reveals much about the Paris Exhibition in 1878 (which included a ‘Negro village’)[1], and the social, political and economic context of empire within which these sorts of expositions took place.

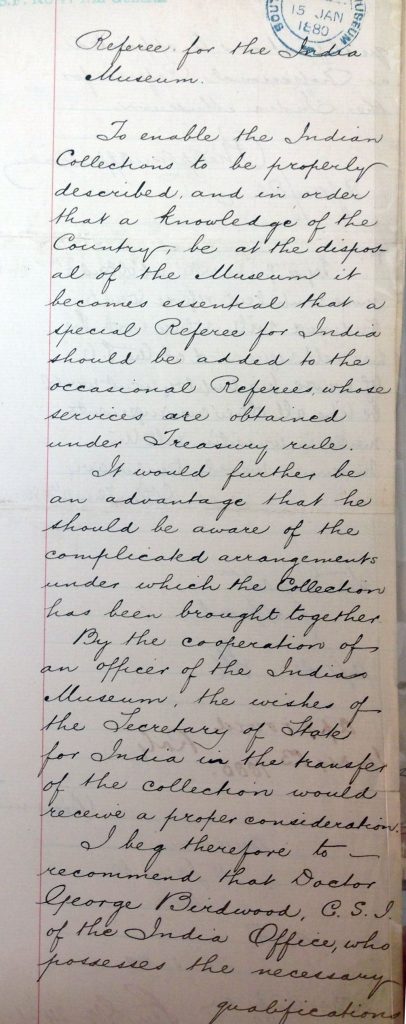

In 1868 Birdwood started working for the India Office, and in 1875 was appointed Keeper of the India Museum. In 1879, the India Museum collections were dispersed to institutions across London, including to the South Kensington Museum, where they now form a significant part of the V&A’s South Asian collections (find out more in our India Museum Research Guide). In 1880, Birdwood became a professional Art Referee for the Indian Section of the South Kensington Museum. Generally, these referees acted as consultants, suggesting and advising on purchases for the museum (find out more in our Art Referees Research Guide). Birdwood’s appointment as a ‘special Referee’ had the advantages of enabling ‘the Indian Collections to be properly described’ and ensuring ‘that a knowledge of the Country be at the disposal of the Museum’ (India Museum General, archive ref. VA 170 part 3). While he was initially regarded as an authority on Indian art, and of course had a big impact on the collections, his standing was later brought into question when he stated at a 1910 Royal Society of Arts meeting that no ‘fine art’ existed in India, prompting backlash from his peers.[2]

Although it is perhaps surprising to see correspondence with the ‘Universal Races Congress’ in the V&A’s archives, in fact it makes perfect sense that in a discussion of race, the Congress would approach the museum for relevant literature. Ideas of race and civilisation were arguably central to the experience of art at this time. In the museum’s role within the British government, its interactions with the wider world through the British Empire, and its role in bringing pieces of that world back to Britain, it couldn’t help but be enmeshed with these ideologies.

If you would like to find out more about files such as the one above or any other material we might hold, or make an appointment to view material, you will find relevant information on the V&A Archive page. Access to the archives is via the Blythe House Archive & Library Study Room, which is located at Blythe House, 23 Blythe Road, London W14 0QX, and is open Tuesday to Friday from 10.00 – 16.30, by appointment.

[1] Lefaivre, L. and Alexander Tzonis, A., Architecture of Regionalism in the Age of Globalization: Peaks and Valleys in the Flat World (Routledge, 2012) p.104

[2] ‘George Birdwood’, Making Britain website, The Open University; accessed 20 March 2019