by Philip Kevin, Furniture Conservator

A significant proportion of the Museumu2019s collections are currently stored at Blythe House in west London. Preparations began last year to get them ready for the move to the new Collections & Research Centre (CRC) at Here East in the Olympic Park, which will open in 2023. In addition to a complete audit of the collections at Blythe, condition assessments were carried out to evaluate the stability of the objects before packing begins. Two furniture conservators are currently working as part of the Blythe House Decant team, treating and preparing furniture and other wooden objects including, carvings, picture frames, architectural elements and puppets.

With over 250,000 objects to move and limited resources, difficult choices must be made when deciding which objects get allocated precious time in the conservation studio. The process is not without challenges, but it is also very rewarding, and even small interventions can significantly reduce potential risks to the objects. Most of our treatments will focus on stabilising the objects to minimise potential damage during transportation, working closely with Technical Services decant team to achieve this end. Many treatments are non- interventive and involve specialist packing, additional handling boards, boxes, crates and packing with protective museum-grade foam and tissue. Practical treatments often include stabilising flaking painted surfaces. However, there are some cases where more is needed; the small English japanned toilet mirror (Museum No. 661-1906) c1700-1725 is one such example (Figure 1).

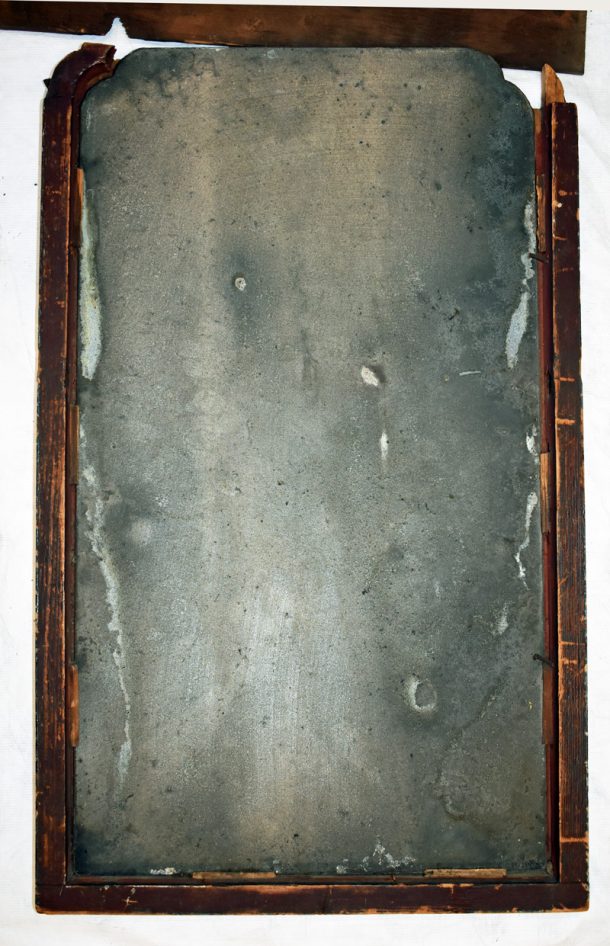

The mirror was in poor condition: the frame was broken at the top with losses on one side, the top cresting had become detached, the decorative japanned surface was flaking, and localised old woodworm damage was causing some structural weakness and loss of wood. A turn screw that secured the mirror in place and allows it to tilt was missing, and a non-original escutcheon (keyhole plate) had become detached. The broken frame and a loose backboard had created large gaps which had allowed dust and cobwebs to accumulate behind the glass. The toilet mirror is a tin mercury amalgam mirror, a technique used to make mirrors from the sixteenth century right up to the twentieth century. These types of mirrors are susceptible to degradation as the tin component of the amalgam oxidises and separates from the mercury, dulling areas of the mirror (Figure 2). The mercury can be released into its liquid state, sometimes causing small droplets of mercury to form at the bottom of the mirror. Contact with dust and direct contact with the wooden backboard accelerates this process.

With the enormity of the decant project, re-attaching separated/broken fragments, repairing breaks and reconstructing losses is not always possible, or necessary. In many instances these objects can travel safely with supportive packing. However, in this instance there were several reasons why a full reconstruction of this object was deemed necessary:

- The frame was broken and the mirror was close to falling out.

- The mirror was taking up more shelf space in pieces than it would if reconstructed.

- Mercury can be hazardous and skin contact should be avoided. Reframing the mirror securely in its frame is the safest way to store the mirror and reduce this hazard.

- Reframing the mirror would allow the mirror to be displayed and stored in an upright orientation to minimise the risk of breaking.

- A gap should be maintained between the back of the mirror and the inside of the acidic wooden backboard to slow down the deterioration of the amalgam and help inhibit the corrosion process.

- Reconstruction would reduce the risk of further loss and damage to the broken wood edges, making a future treatment more difficult.

- Reconstruction would also allow the opportunity to carry out some consolidation of the decorative surface. Areas of the component parts normally not accessible when assembled could be accessed before it is reconstructed. With the mirror in pieces, consolidation and flake laying the surface of the elements piece by piece is easier as you are not trying to work against gravity.

- A reconstructed frame could be made dust resistant to further protect the back (amalgam side) of the mirror.

To carry out the reconstruction of the frame, the backboard was first removed. The backboard was held within the rebate with steel cut nails; these had corroded badly and were removed but were not suitable for reuse. Makers knew the importance of separating the backboards from the back of the glass and they used small triangular blocks to create this gap. These blocks were also removed so the glass could be lifted out of the frame to allow the necessary repairs to be carried out. To stabilise the frame, reconstruction of the broken side was necessary. There were substantial losses at both the front and back of the frame around the break (front view Figure 3a). These losses were replaced with new wood to make the frame stable again. Softwood blocks were glued in position front and back and carved to the shape of the lost pieces of japanned wood (Figure 3b). This made the frame rigid and strong enough to carry the weight of the heavy glass and backboard. The new wood was later stained and coloured in a neutral colour matching the dark blue/green background of the surrounding japanned decoration. The loose dovetail, which originally attached the cresting to the frame, was lost. A new softwood dovetail was cut and secured into the dovetail housing and glued to the back of the cresting, replicating how it was originally secured (Figure 4).

Several of the old triangular retaining blocks or wedges used to secure the mirror in the frame needed replacing as they were damaged. The original damaged retaining blocks were bagged, labelled and placed within a drawer of the toilet mirror.

Shrinkage had caused gaps to form on either side of the backboard between the outside vertical edges of the backboard and the frame rebate. Wood shrinks more across the grain (backboard width) than along the grain (backboard length). These gaps allowed dust to accumulate and insects to gain access behind the glass. Thin fillets of soft wood were glued along each side and planed to size to create a snug fit between frame and backboard (Figure 5). Brown gummed tape was applied to the mirror side of the board, where knots in the wood had become loose and tiny holes were visible, to secure the knots in position and keep out dust.

The corroded cut nails were replaced with a different system to secure the backboard in place. Small square blocks were attached to the rear rebate with brass screws. The blocks and screws will allow future conservators easy access to the inside of the frame. Old cut nails were kept with the old retaining blocks inside a mirror drawer. Gummed linen tape was then applied across the rebate gap at the back to further seal from dust while still allowing some air circulation.

One turn screw used to secure the mirror and allow tilting movement on the stand uprights was missing and the one that remained was not original. Following a discussion with the curator it was decided to remove the remaining non-original turn screw and replace with a pair of new turn screws. The turn screw that was replaced was labelled and bagged and placed inside a mirror drawer.

Once conservation treatment was complete, the object was placed within a newly-made bespoke packing case (Figure 6). The case will allow the toilet mirror to be transported to the new storage facility safely. It is proposed that the toilet mirror, along with others similarly treated and vulnerable objects, will remain within their bespoke cases for future storage.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Lee Emment, V&A Technician for help and support with the new carry frame to transport and store the mirror and Zoe Allen, Head of Furniture Conservation for advice on the preservation and treatment of the mirror back.

u00a0