Alicia Robinson, Senior Curator, Sculpture, Metalwork, Ceramics & Glass

Donna Stevens, Senior Metals Conservator

Zoe Allen, Senior Furniture and Gilding Conservator

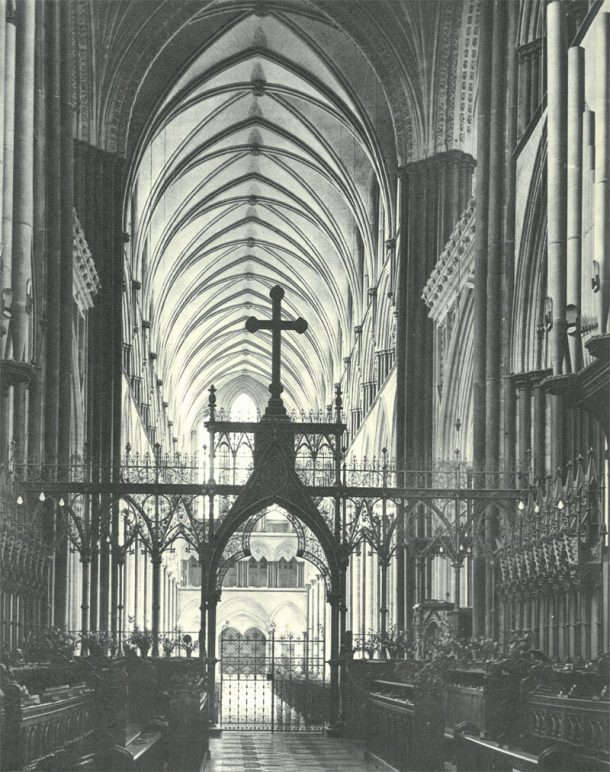

This three metre high cross once on top of the choir screen in Salisbury Cathedral was designed by George Gilbert Scott (1811-1878) and made by Francis Skidmore of Coventry (1817-1896) and erected in about 1870 ( Figure 1). Scott and Skidmore collaborated on some of the most spectacular creations ever made in ironwork, including the Hereford Cathedral Screen (1862, now at the Victoria and Albert Museum) and the Albert Memorial in Hyde Park. When first installed, their cathedral screens were highly praised, but by the mid-twentieth century their ornate Gothic Revival style was out of favour and there was also a move to ensure clergy were no longer separated from their congregations by screens. The Salisbury Cathedral screen was dismantled in 1959 and sold to a metalworker nearby. The central gates from the screen were acquired by the V&A in 1979. The cross was retained by the Cathedral, and the Dean and Chapter generously presented it to the V&A in 2014.

Although the cross was structurally sound the surface had suffered from extensive corrosion with much of the original red and gilded decoration being lost. Different treatment options were discussed. As it would be displayed close to the Hereford Screen (restored in 2001 to show how it would have originally appeared), a similar approach was taken for the cross. It was decided to recreate the cross’s original red and gilded appearance to give a sense of how magnificent the screen as a whole would have looked. However, the top sections of each arm would be left ‘unrestored’ as they were at the time of the acquisition, as evidence of the condition and appearance before treatment, enabling future researchers to have access to the original surface. This article describes a series of traditional and innovative techniques that were employed during the project.

The core structure of the cross is made of soft wood, possibly pine, onto which the decorative metal panels are screwed. On the front and rear, the panels are decorated with two hearts and diamonds. Those on the sides are decorated with a double heart motif. Lengths of beading surround the panels. Some of the panels are cast iron while others are cast brass. At the top, centre, base and end of each arm are two quatrefoils at the front and back. The cross was examined using Gamma radiation to establish whether these were screwed or riveted in position. The radiographs showed they are held in place with a metal rod, with a hemisphere of gilded metal screwed on each end.

Close visual examination and microscopy were carried out to the painted and gilded surface to understand the original techniques and materials used. The cross had been painted and gilded after assembly, evident by the fact that some areas which could not be reached with the brush, such as those below the central and end quatrefoils, were bare metal. Several areas showed the gold leaf overlapping onto the red painted background, indicating that it had been painted prior to gilding. The stratigraphy of the surface decoration showed a yellow oil-based layer directly on the metal; a probable primer, followed by a red/brown layer (mainly iron) and a translucent yellow layer (probable mordant) under the oil-gilded areas.

For dismantling, the metal elements were removed by unscrewing each screw, sometimes with the aid of a lubricant. Some screws had rusted in and required drilling out. Line drawings were created and a labelling system devised to allow a smooth re-assembly and enabling us to keep track of each part during treatment.

Cleaning methods for corroded metal can be time-consuming. The use of dry ice ‘blasting’ as a quicker option to clean some types of museum objects has increased in recent years. Following its successful use to clean gilt metal mounts at the Wallace Collection, V&A conservators had used it to clean the mounts on the Augustus Rex Cabinet (W.63-1977) in 2013. With this in mind, dry ice cleaning was considered for the cross and tests on a small area proved to be effective. The term ‘blasting’ is misleading as it is in fact a very gentle process. Dry ice cleaning involved solid CO2 in powder form being directed onto the surface via the hired Cryogenesis dry ice cleaning unit and compressor. Upon impact, the dry ice immediately turns into vapor and rapidly expands. This expansion removes all the loose corrosion and dirt on the surface (Figure 2).

After this process, each part was wiped with IMS prior to painting. An exact copy of the original paint colour was specially made by Craig and Rose. Areas with the most intact original decoration were coated with a barrier layer of Golden Fluid Matte Medium Acrylic prior to painting. The best match to the original leaf was found to be 23¾ carat. It was applied to a 12 hour size pigmented with yellow oil to enable the sized area to be visible for gilding (Figure 3). Each of the quatrefoils had two brass leaves on each lobe. There were originally 64 and of these, only 10 heavily corroded ones remained. To make replacements an original leaf was scanned and a CAD drawing produced. This was used to make a new 3D leaf printed in plastic with a smoother surface than the corroded original. This leaf was used as the model for the new leaves which were cast in brass, polished and lacquered using Frigilene pigmented with a yellow dye to protect against tarnishing (Figure 4). Due to its weight the cross was reassembled in situ in the gallery (Figure 5).

Acknowledgements

Grateful thanks to James Joll, John Scott, the Ironmongers Company, the Worshipful Company of Arts Scholars, and other supporters. Thanks to Katie Snow (ACON) and Aude Lafitte, Metals Conservation intern, for their help with the project.

Further reading

Robinson, Alicia; Lauded, Lambasted, Lost and Found: The Salisbury Cathedral Cross by George Gilbert Scott and Francis Skidmore’, Journal of the Antique Metal ware Society, Vol 23, 2015, pp. 2-17.

Campbell, Marian; The Hereford Screen by Sir George Gilbert Scott, 1862: http://www.vam.ac.uk/content/articles/t/the-hereford-screen/