Commemorative medals combine portraiture with designs that commemorate their subjects’ principal deeds. This medal was made to celebrate the success of Louis XIII, King of France, in forcing the passage of the Pas de Suze (the Suza Pass) in January 1629. It will feature in The Cabinet gallery display, which will explore the types of objects collected in the 17th century.

The obverse (or ‘head’) of the medal shows a portrait of Louis XIII wearing a ruff, armour and the sash and cross of the Order of the Holy Spirit, which was an order of chivalry under the French monarchy.

As King of France, Louis was the Sovereign and Grand Master (Souverain Grand Maître) of the Order of the Holy Spirit and made all appointments to the Order. A more youthful Louis can be seen wearing a ruff and the collar of the Order on this medal (dated 1610), which will also be displayed in The Cabinet.

Whilst Louis’ locks and extravagant neck-wear may be quite attractive, it is the reverse of the 1629 medal which really has my attention.

This side of the medal not only depicts a naked Hercules in a rather defiant pose, but also commemorates the Passage of the Pas de Suze. This was an episode which saw Louis XIII’s troops force their way through the Duchy of Savoy (now in the Italian Piedmont near the French border) to intervene in the War of the Mantuan Succession.

The War of the Mantuan Succession

The War of the Mantuan Succession (1628–31) was a peripheral part of the Thirty Years’ War. In an attempt to keep things simple here, I will describe it as ‘quite a spat’ that resulted from the extinction of the male line of the House of Gonzaga.

The male line of the Gonzaga dynasty had ruled over the ancestral city of Mantua. Once the male line came to an end, there arose two rival claimants to the sovereignty over the marquisate of Montferrat; Ferrante II, Duke of Guastalla (supported by Emperor Ferdinand II), and Charles Emmanuel I, Duke of Savoy.

When the Duke of Savoy moved his troops to lay siege to the town of Casale, capital of Montferrat, near the border with Milanese territory, Louis XIII sent his forces to help relieve the besieged town.

The Pas de Suze

Louis left Paris on 15th January 1629 and on 6th March he sent an emissary to the Duke of Savoy to request the right of passage for his troops through the Duchy of Savoy.

This request having been denied, it was decided that the French troops would force a passage in the Susa (also spelled Suza) Pass, which the Duke of Savoy and the Prince of Piedmont were both defending.

The French were victorious in this endeavor and on 11th March, Susa and its castle capitulated.

Following the French capture of the city, a treaty between France and Savoy was signed at Susa on 11th March 1629. The terms of the treaty allowed the French military passage through Savoy to assist in relief of the siege of Casale.

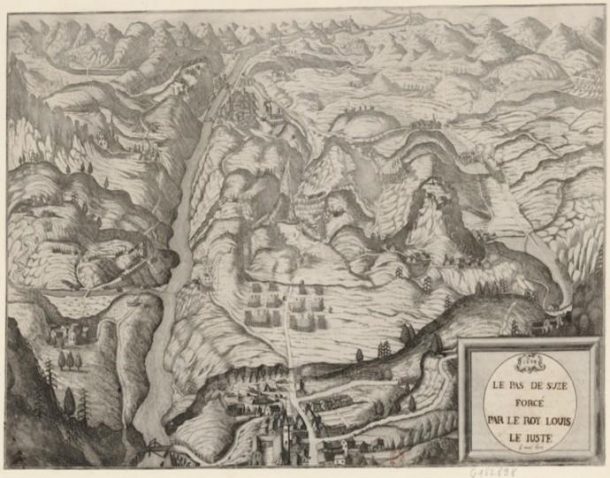

The gorge which the Suze Pass went through can be seen in the background of the reverse of the medal, with soldiers and fortresses visible on the mountain.

The Siege of La Rochelle

On the left-hand side of the background, the sea port of La Rochelle is depicted, along with a fleet of ships. This probably refers to the Siege of La Rochelle which took place in 1627, two years prior to the Pas de Suze.

The siege resulted from the war between the French royal forces and the Huguenots of La Rochelle and is considered to mark the height of tensions between Catholics and Protestants in France. It may already be familiar to some of you, as it forms the historical background for Alexandre Dumas’ novel The Three Musketeers.

Louis XIII’s troops laid siege to La Rochelle in 1627. The city mounted a long and vigorous resistance and was supported by the English, whose fleet appeared off the French coast in May 1628. However, the English fleet failed to overthrow the French and retreated – the ships depicted on the medal may represent the retreating English fleet.

La Rochelle held up for just over a year, but the siege ended with an unconditional surrender and victory for Louis XIII and the French Catholics. It is claimed that during the siege, the population of La Rochelle decreased from approx. 27,000 to 5,000 due to casualties, famine, and disease.

Interestingly, during the siege a number of coins were produced by the French mint as propaganda pieces, symbolically expressing the power of the French forces. One of these designs depicts a vanquished English ship and another appears to show an English snail pierced by an arrow on a raft.

Louis XIII as Hercules

In centre of the design, Hercules (the Roman name for the Greek divine hero Heracles) stands astride a mountain. Here, Hercules represents the Louis XIII and has been given Louis’ facial features.

He is carrying a club and wears the skin of the Nemean lion which, according to Greek mythology, he killed as one of the twelve ‘Labours’ or challenges he was set. Fittingly, the medal will be displayed in The Cabinet within view of a distinctly larger depiction of Hercules, also wearing the Nemean lion skin.

Jean Warin – ‘Master of Medals’

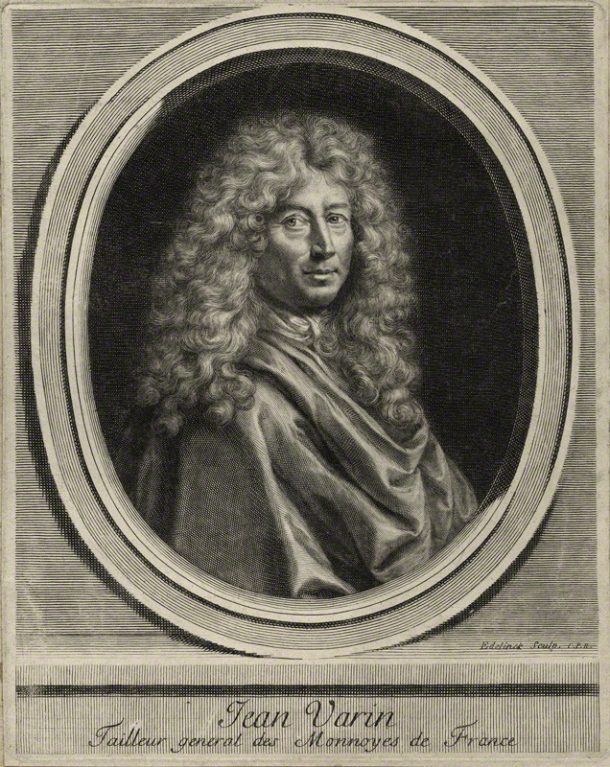

The medal was made by the French sculptor, painter and medallist Jean Warin (also known as Varin). Warin was one of the most eminent French medallists of the period and enjoyed a considerable reputation as a sculptor.

Warin was born in Liège in 1606, where his father worked for Prince Bishop’s mint. Warin trained in his father’s workshop and in 1626 travelled to Paris where his uncle, Guillaume, worked as a wax modeller and his cousin Jean was a goldsmith.

He entered the service of the Count de Rochfort and was soon distinguished by Cardinal Richelieu, a man who was immensely powerful in both the Catholic Church and the French Government. Richelieu entrusted Warin with overseeing the new coinage of the kingdom. February 1629 saw Warin placed in charge of the Monnaie du Moulin, one of the two mints in Paris.

Traditional practice was for coins to be produced by being hammer-struck but at the Monnaie du Moulin technology developed in Germany was being used to mechanise production. By mastering the machinery at the Monnaie du Moulin and developing techniques from the Italian renaissance, Warin revolutionised the production of coins and helped to transform them as an art to serve the state.

In 1635 Warin engraved the die for the seal of the Académie Française and included a bust of Cardinal Richelieu in the design. Gestures like this helped to maintain and encourage the support of Richelieu which was particularly useful to Warin, especially when he was accused of forgery and other misdemeanors.

Warin later took charge of the studio of the Lyon mint around 1642-43, and in 1646 was appointed Tailleur Général des Monnaies de France. When the mint later moved to the Louvre, Warin added to his title that of ‘Chief Engraver of Dies’.

Warin’s most famous production was a series of medals commemorating the triumphs of Louis XIV’s reign; an entire medallic history conceived by the King’s Controller-General of Finances, Jean-Baptiste Colbert, in 1662.

To finish, as Alicia Robinson (Curator of Metalwork) has previously described, Warin: ‘revolutionised not only the production of medals, but also their function in propagating image and iconography in the service of the state’. This medal, celebrating Louis XIII (as Hercules) triumphing over his enemies, is a clear example of a finely produced medal that clearly broadcasts a triumphant and powerful image of the Louis XIII and his deeds.