Lockdown has brought about a mass experiment in home cooking as the hospitality sector has pulled down its shutters leaving people largely to their own culinary resources. Initially dried pasta – a go-to ingredient for quick meals – emptied from the supermarket shelves. In the following weeks, however, flour and yeast have become the two most-discussed ‘scarcities’. In countries that have a traditionally wheat-based diet, people have been turning their hand to baking their own bread. People, that is, who are able to stay safe at home and are food secure. In the midst of a public health catastrophe, a craze for baking is an incidental phenomenon. It does, however, reveal something both of our behaviours during the pandemic, and the ever-evolving significance of bread as a cultural object.

Bread is a classic comfort food, full of serotonin-boosting carbs, but also rich in symbolism. One of the commonest and most ritualised foods throughout history, it is synonymous with physical and spiritual sustenance. On the broadest level, bread can embody a reassuring sense of continuity and human resilience in the context of crisis and uncertainty; “a kind of promise that we’ll get through it”, as one historian puts it. Beyond that, there are a number of ways in which making bread at home corresponds with the conditions of lockdown.

Touch

There is something to be said for the very tactile pleasures of bread-making during the experience of social distancing when physical contact has become the subject of regulation and fear. Bread has long been associated with bodies, from bread as the body of Christ in Holy Communion, to the earthier connotations of folding your hands into pliant, pillowy dough. Kneading a bread dough feels good and releases tensions. The pure alchemy of transforming flour, yeast and water into a gloriously risen loaf is creatively satisfying: a tangible result you pull from the oven, taste and ingest. Lockdown means more of our lives than ever are digitally mediated. It is easy to feel we’ve all been reduced to heads on screens. Perhaps on the most visceral level making bread re-affirms our bodily existence.

Home

And then there is the smell; warm, slightly heady, and redolent of all things homely. The aroma of baking bread is powerfully associated with a wholesome ideal of home, even when it has never featured in most of our home lives. It is cliché that having bread baking in the oven helps to sell a house by subliminally presenting it as a home. Confined to our houses, making bread is part of the script for embracing the enforced domesticity and creating home as a place of sanctuary and retreat from the world; a script that was all too familiar to the stay-at-home 1950s housewife. It can also be approached as a mini exercise in homesteader-style survivalism: if you want fresh bread, making your own means you can hold out longer before leaving the shelter of home and venturing to the shops.

Time

Equally, the practical process of making bread fits well with the directive to stay at home. Baking a basic loaf isn’t labour intensive: overall the prep takes less time than watching an episode of Bake Off. But it does require you to be in one place for several hours ready to intervene at the right moment in the various stages of kneading, proofing and baking. The rhythm of bread making can feel impossible to square with the frenetic pace of modern life. But when schedules vanish overnight, the opposite is true – making bread can create a structure and routine (which is one of the reasons it is often taken up by people – men in particular – when they retire). Arguably making bread in the current crisis is less about filling time, and more a response to an altered sense of time. It is a slow activity at a moment when the repercussions – and potential benefits – of slowing down have become a subject of intense discussion.

Image

In another sense, however, bread-making is feeding the familiar pressure to always be producing, consuming, and communicating. Because we’re not just baking loaves, we’re photographing them and posting them on Instagram. A friend of mine recently uploaded a video of himself squeezing orange ‘Easy Cheese’ from a tube onto a salty cracker, captioned ‘Some of my friends are making sourdough…”

It was a pointed comment on how baking bread, especially complex sourdoughs, has become a favoured method of showing the world that you are having a ‘productive lockdown’. With so many activities commonly used for communicating status and identity via social media suspended, others are taking their place. According to Andrew Potter, author of the Authenticity Hoax, when you share images of your sourdough efforts, you are signalling that you have the privilege and resources to develop new skills during lockdown as opposed to simply surviving. The issue of inequality becomes even clearer when we consider that the sudden boom in recreational baking means that workers packaging flour for retail are having to work overtime on factory lines now operating 24 hours, seven days a week.

The most radical consequence of the disruption to our food lives would be that we start to take more notice of where our food comes from, how it reaches us, and who actually produces it.

This article was originally written on 20 April 2020

Further reading

- Shapeshifting dough? An interview with artist Laura Wilson, , May Rosenthal Sloan

- As the coronavirus upends their lives, the French flock back to bakeries for comfort, , James McCauley, Washington Post, 10 April 2020

- Coronavirus offers “a blank page for a new beginning” says Li Edelkoort, , Marcus Fairs, Dezeen, 9 March 2020

- Every 20-Something Is Now Obsessed with Making Bread, Jack Cummings, Vice, 3 April 2020

- Issue 15: Sourdough, Status, and Self-Isolation, Andrew Potter, 10 April 2020

- Why there’s still no flour in supermarkets – and it’s not just because everyone is baking in coronavirus lockdown, Josh Barrie, inews, 3 April 2020

Related objects from the collection

Watercolour, ‘The Kitchen at Elmswell Manor House, York’, by Mary Ellen Best

Mary Ellen Best (1809 – 91) was a highly skilled watercolourist. She specialised in views of domestic interiors and designed some herself. The depiction of this kind of interior in such accurate detail was quite unusual at this period. Some of the arrangements seem to be a bit makeshift, particularly the way the dough trough is supported by a chair. The chairs look as if they date from the mid 18th century. They were probably relegated to the servants’ area when the dining room of the Manor was more fashionably decorated. The woman is probably the cook, one of a number of servants tending a wealthy family.

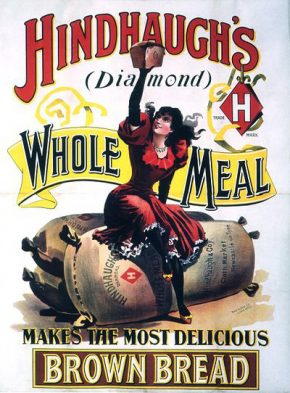

Poster, ‘Hindhaugh’s Whole Meal makes the most delicious brown bread’, printed by Perry & Sons

Colour lithograph poster depicting a woman in a synched red dress, sitting on a large bag of flour stamped ‘Hindhaugh & Co. Cloth Market, Newcastle on Tyne’. She is smiling and holding a smaller bag of flour aloft.