The flower industry was hit particularly hard by Covid. With weddings, anniversaries, and other social events cancelled, suddenly the need for buying and gifting bouquets and arrangements vanished. Flowers wilted and decayed, truckloads were dumped in fields, or were used for fodder and compost. In the Netherlands, the hashtag #BuyFlowersNotToiletPaper was circulated in a bid to rescue its beloved national industry. While in London this particular crisis was felt with the closure of flower shops, there were – as with so many things about Covid – knock-on effects elsewhere at the other end of the supply chain, out of sight of the average consumer.

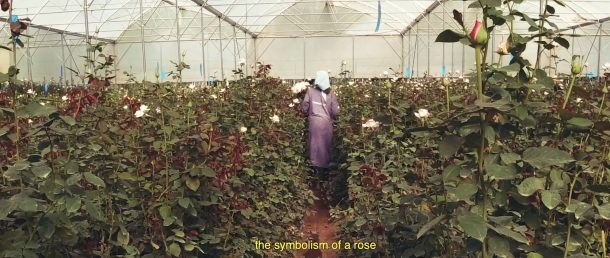

One of those places is Kenya, where a massive rose industry has grown over the past few decades. Because of the pandemic, tens of thousands of flower workers were sent home without pay – workers who already led precarious lives due to the low earnings of their job. At the same time, massive crops of roses were left out in the fields to bake in the sun.

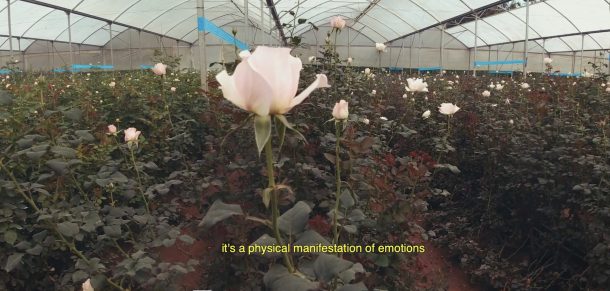

Cole McDowell captures these haunting scenes in his brilliant ‘The Scent of Economic Loss’, one of the standout films currently featured in the Design Film Festival hosted by the Design Museum and curated by the students from MA Curating Contemporary Design, Kingston University. McDowell, currently a student in the Social Design programme at Design Academy Eindhoven, spent several months on the Tambuzi rose farm in Kenya using his iPhone and a GoPro to document the changes unleashed on the land by Covid-19. Throughout this period he also worked with the farm owner to set up a system for distilling the flowers into rose oil, rescuing some of the production from oblivion. The narrative of the film poetically explores the nature of global supply chains and the rose as a symbolic and fragile carrier of value.

The problem of sudden surplus and plummeting demand has hit several industries at once during the pandemic. Like the rose itself, the crisis is fundamentally questioning what is essential and what is non-essential, and inflicting pain everywhere in terms of layoffs and so-called ‘zombie jobs’ that might never return. But in McDowell’s effort to save some of the surplus flowers by converting them into rose oil, there’s a powerful story about how design can help us think about managing change. What’s needed now more than ever is creative thinking into how existing infrastructure, materials and labour might be both preserved yet somehow re-configured to continue adding value in our changing world. On a more personal note, this metaphor can even be extended to museums, which are now confronted with looming budget shortfalls and staff reductions given the projected lower visitor numbers over the next few years. If the museum is the rose, then what is the rose oil? What new forms can a museum take, which both preserves the knowledge and expertise of its staff, but also produces something entirely new?

Further Reading:

‘Kenyan worker tells her story of a flower industry devastated by Covid-19‘ , Anna Barker, Fairtrade Foundation, 28 April 2020.

‘Flower Power‘, Het Nieuwe Instituut, 8 May 2020.

Related Objects from the Collections:

‘Summer for Roses. See London’s Gardens.’ designed by Dora Batty for the London Underground, 1927 (V&A: E.501-1929)

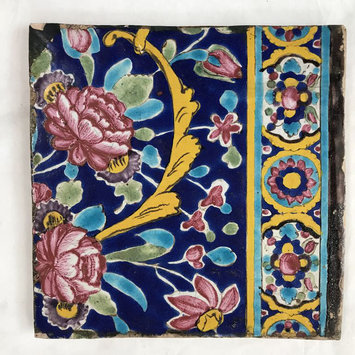

‘Roses from Tehran‘, earthenware tile, Iran, 1850-70 (V&A: 1531:44-1876)

‘Roses’ biscuit tin, Huntley & Palmers, England, 1909 (V&A: M.335-1983)