The important and timely work of Peruvian artist Tarrah Krajnak critiques the canon of Westernised photography to reimagine, replay and reclaim it, as an Indigenous woman of colour. Her interests include the notion of the ‘archive’ and specifically what and who is remembered, and how. A group of her cyanotypes form the first Parasol Foundation Women in Photography acquisition.

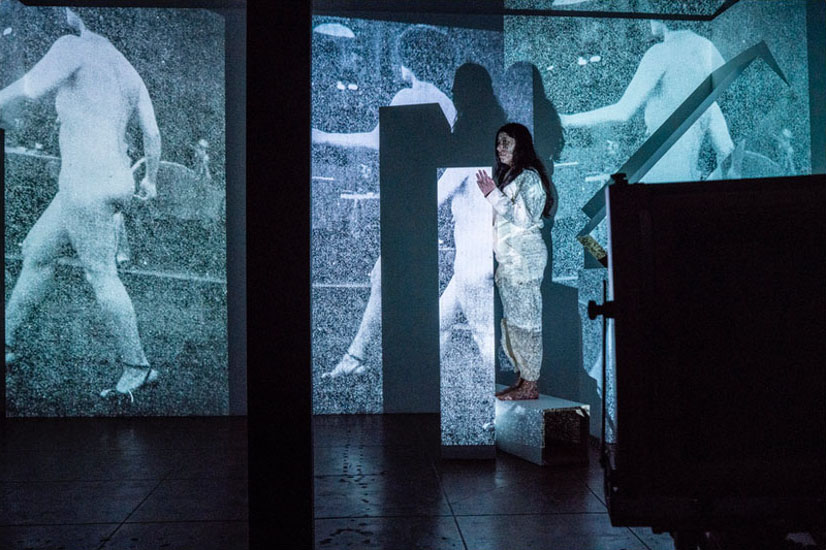

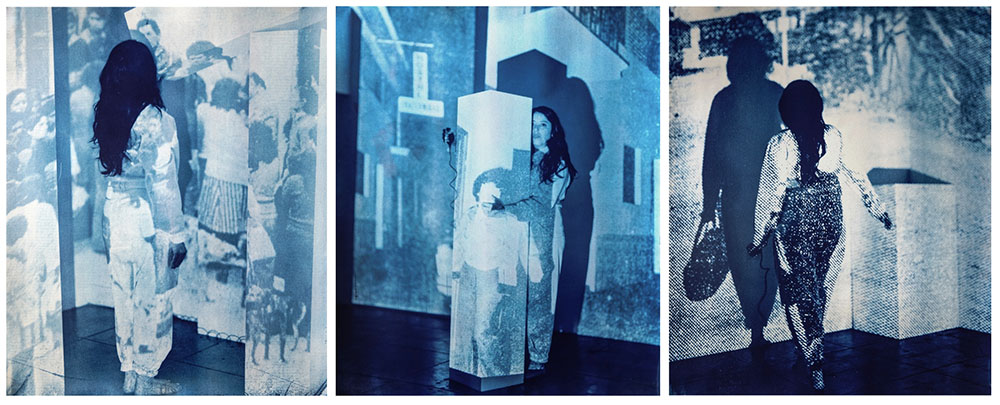

1979: Contact Negatives was a staged performance in which Krajnak projected newspaper images of Peru’s violent political upheaval during the year of her birth on to herself. As the self portraits imaginatively ‘return’ her body to her birthplace to explore her unresolved identity as a Peruvian woman, these pictures make visible how personal and collective memory is constructed and archived. The acquisition meets the Parasol Foundation Women in Photography program remit to support contemporary living artists and highlight the contribution that women of colour make to photography.

The acquisition will go on display next year, as part of the opening celebrations and inaugural exhibition within our Photography Centre.

Fiona Rogers / Tarrah, we are absolutely thrilled to have your work enter the Photography Collection as the first Parasol Foundation Women in Photography acquisition. I wonder, if you could tell us a bit about yourself?

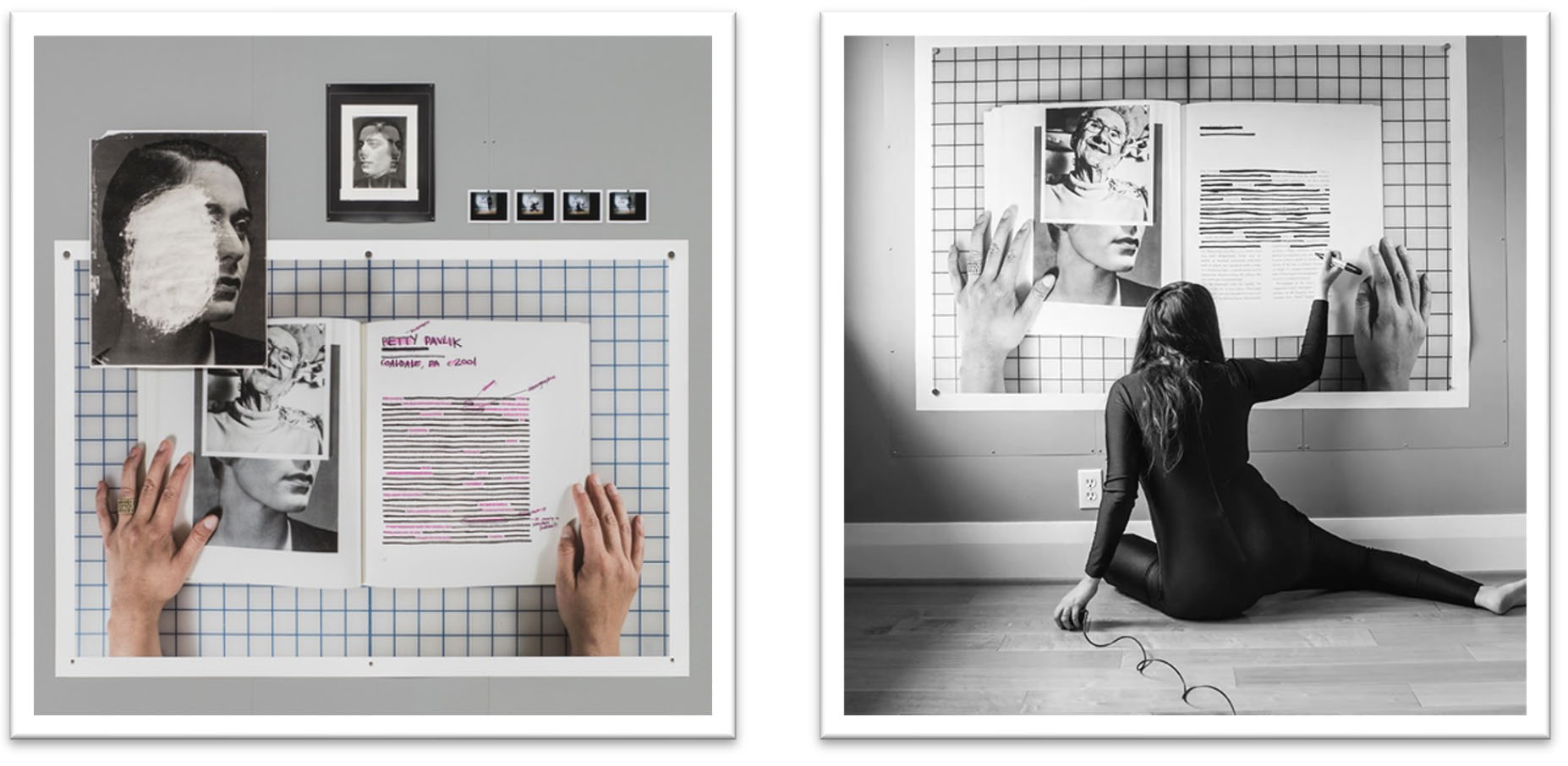

Tarrah Krajnak / I was born in an orphanage in Lima, Peru, in 1979, to a young unwed mother who subsequently disappeared, leaving me in the care of Catholic nuns. Within months, I was adopted by Slovak Americans from Coaldale, a mining town in eastern Pennsylvania. I was raised as a twin to my adoptive black brother along with other adoptive siblings in a nearly all white suburb in Ohio, in a household without art, books, or music. I had no exposure to photography, aside from one Ansel Adams poster and albums of vernacular family photographs that my mother kept.

I discovered photography as a first generation college student in a basement darkroom at Ohio Wesleyan University. I had been on the path to medical school when I got sidetracked by analogue film and the 90s Ohio rock scene. My heroes were Minor White, Francesca Woodman and Robert Pollard. I shot portraits of my friends with a 35 mm camera. I scratched my negatives, and experimented with chance processes. My final year at OWU I moved to New York and shot celebrity guests and musical hosts for Saturday Night Live (SNL). A year later I returned to the Midwest ready for graduate school.

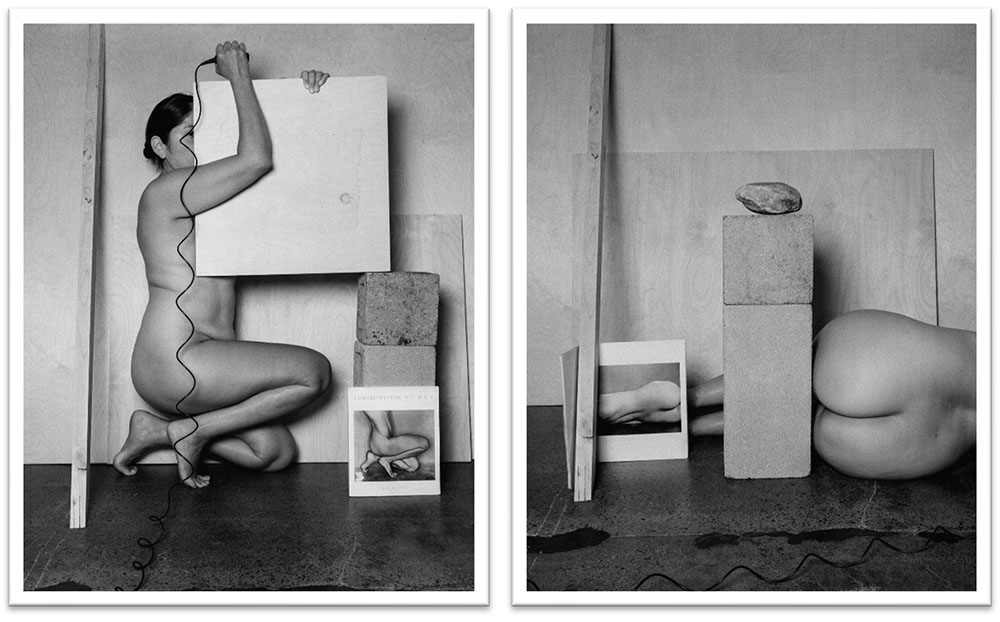

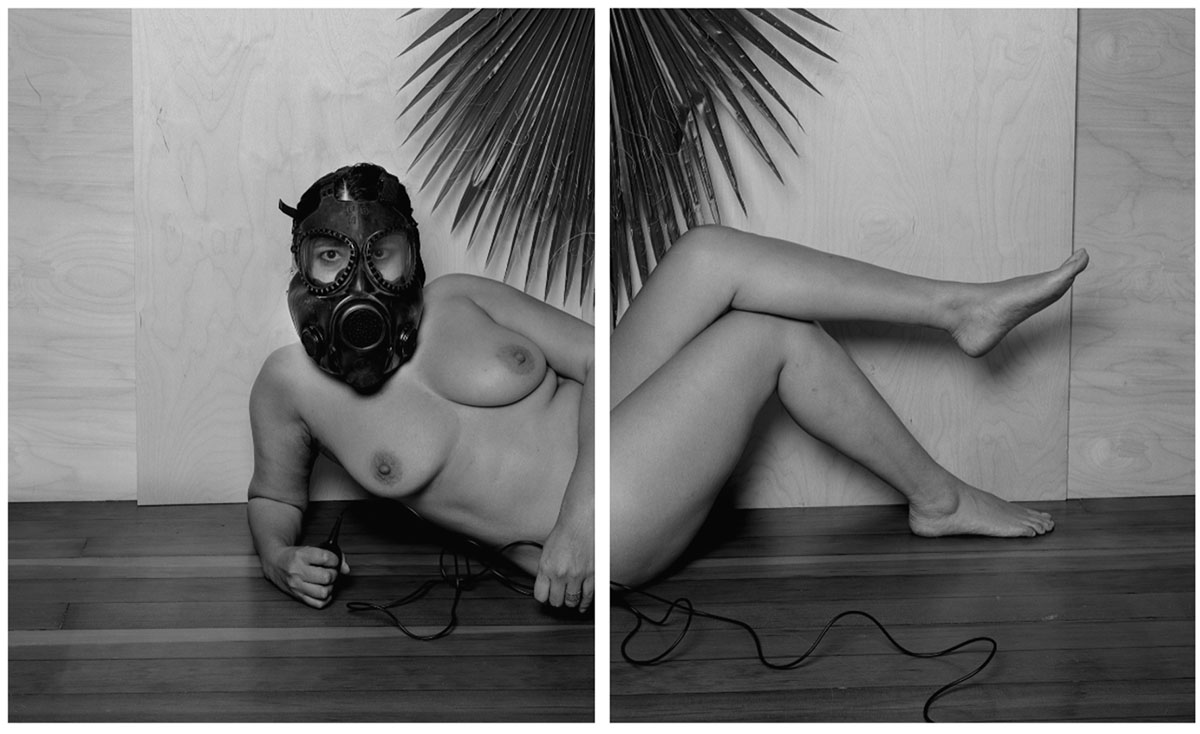

FR: The use of the body, your body, in your artworks is a recurring theme and features in your seminal series Master Nudes and our acquired series, 1979: Contact Negative. Your use of performance feels reminiscent of 70s feminist art, and Latin American’s political art movement, as personified by artists such as Ana Mendieta and Sylvia Palacios Whitman. Can you talk a bit about this in relation to your work, and perhaps some of your artistic influences?

In terms of artists, yes, I connect with Mendieta’s Siluettas and Body Tracks because I see these works as related to exile and a deep desire to reconnect with what has been lost. In my own work themes of exile, belonging, and exclusion are at the centre of my practice. In 1979: Contact Negatives I weave together performance, archive, and re-photography to create what Saidiya Hartman refers to as a speculative historical narrative. The work pushes against the traditional documentary form and offers in its place a poetic meditation on parallel existence, the mythology of origins, and the painful history of Lima about 1979 including violence against women, mass rape as a weapon of war, and the trauma hidden in the photographic archive. Aside from Hartman, I am inspired by poets like Don Mi Choi, Solmaz Sharif, and Layli Longsoldier. I have studied with some of these women in my search for strategies to confront the difficulty of historical trauma. Theresa Hak Kyung Cha is another artist especially important to me because her work has a lot to do with language and writing as performance. All of these women are interested in similar questions: What is written onto the body? Or how does the body hold history? How might we understand epigenetics?

FR: Your work exposes several highly topical, important themes relating to representation and agency, in exploring and processing your personal history but also in relation to a collective history of the Peruvian nation and its trauma. As an indigenous woman, brought up in North America, how does the act of ‘being seen’ inform your practice? Which audiences are you hoping to engage with your work and what do you hope they take away from it?

Over the last decade my work has examined my own relationship as an indigenous transracial adoptee to the larger social, political and historical narratives of my birthplace and year; Lima, Peru about 1979. The questions I ask are ones to do with photography’s ability to document orphanhood, absence, invisibility, erasure, and post-memory. I am just one of an entire generation of indigenous children displaced by illicit international adoption practices. Our very life circumstances represent decades of socioeconomic inequality, corruption, and instability not just in Peru, but globally. Our transracial adoptions by white American and European families are a continuation of the colonial power structures used by governments to erase indigenous bodies and cultures, but we are indeed still here and we demand to be seen. Many of us, now well into adulthood, are organising to reclaim our rightful native ancestry, voting rights, and to demand an official apology from the Peruvian government.

I want my work to reach a wide audience, but I also understand that it requires careful reading and looking. Like much of the complex artwork that I admire, I think there is always a way an audience can engage with my work as photographic object – aesthetically they’re beautiful and they contain a lot of visual information for an audience to look at and contemplate. ln the context of the museum, however, my works can have a different life because I imagine there is an opportunity to ‘frame’ it within the historical narratives referenced. What I mean by this is that titles and carefully written wall text, and curation, serve an important role in opening more difficult works to a wider audience.

FR: 1979: Contact Negative uses performance, photography and the analogue process of cyanotype printing. Can you explain the significance in choosing a historic, 19th century process for this project?

I am committed to the materiality of the medium of photography, but I don’t mean this in terms of technological shifts; when I speak of materiality I mean the making of the photograph itself as a spiritual process, one where my indigenous body, my hands, my body’s deep memory becomes embedded and embodied into the photographic objects I create. These ideas stem from the medium’s early, spiritualised history, along with a related belief in the camera as a way of making the invisible visible, as well as the way 19th-century occult imagination of photography fed a visual culture obsessed with archival practices, racial taxonomy and ethnography. These cyanotypes were made from several re-photographic processes. I collected and rephotographed vernacular photographs and print material from my birth year, and I then projected these images onto my body in a ‘live’ performance setting where I rephotographed them again into photographic objects. The cyanotype requires a contact print or a negative the same size as the final print. I love that one to one idea of making ‘contact’ or connecting with the dead, all that it conjures … hand coating, washing, care … the history of cyanotype as a ‘woman’s medium’. Finally, you just need light and water to make a cyanotype. You don’t need to be under red light and it lent itself well to a ‘live’ performance.

FR: You reference an interest in archives and collective memory, specifically in ‘who’ gets remembered and how. Both Master Nudes and 1979: Contact Negative examine the ‘gaps’ or erasure of historical narratives; perhaps you can elaborate on the importance of rebalancing these issues through your work?

Sure, I can answer this a number of ways, but I think the idea of ‘making visible’ isn’t the same as ‘representation or representational justice’. I do not think my work aims to ‘correct’ the archive or ‘rebalance’ the canon through representation. I don’t believe that it’s possible honestly … or that it is that easy maybe. So, rather, my work aims to pose questions about canon-making itself, and the processes by which we remember, or the ways history is written or about the photographic medium itself. I do not think it offers answers. For example, I am interested in expanding the documentary form. I use the camera not in an attempt to document the world as it presents itself, but as a way to remember the land I was exiled from, to resurrect the bodies of my ancestors, and to re-belong. I think BIPOC photographers have to sometimes invent histories because our histories, our ancestors have been erased and genocided. I am always coming to the medium with this deep sense of loss, of trying to recover what has violently been taken away, stolen, etc. I can’t rely on the ‘white man’ tropes of the medium to do this work.

FR: The Parasol Foundation Women in Photography programme looks specifically at the gender gap in our photography collection and programme, and by extension, intersectionality and with a focus on women of colour. How do think big institutions can best represent these historic gaps, and as an artist, how do you engage with museums in a way that feels authentic to your practice?

I think museums and institutions need to take a more critical look at their own histories, objects, and start to make visible the ways they have been agents of white supremacy. I think museums could do more in terms of reparations, reparative justice and returning indigenous objects to their rightful communities. Collecting women and BIPOC artists is a starting point, but our work is simply not valued in the ways that our white male counterparts’ work has been valued over time, which has allowed for white canons to be written and sustained.

For a long time I built my career showing at non-profit spaces and community colleges so I am still negotiating how to best engage with museums. My best experiences are ones where I have the opportunity to engage in dialogue, discussion, and contextualisation. I think curators like yourself are so important to equity and inclusion. You have taken the time to ‘usher’ my work into the museum context with care. This very interview gives me a space to have a voice as well. While panels, discussions, educational programming may seem secondary, I do think it is a chance for artists to ‘be present’ and these are important parts of engaging with a museum.

FR: As well as being an artist, you have a demanding teaching job – how do you balance this with such a prolific and hands-on artistic practice, and how does teaching inform your work?

Teaching allowed me to make art for 20 years outside the demands of the art market. I worked slowly on whatever I wanted and by my own rules. For this time, I am forever grateful for the privilege of teaching. That said, teaching is really amazing, but academia is not. I keep telling my grads that teaching is not just teaching – it is all of the invisible labour of running an institution which can be exhausting. Intellectually the questions I pose in my work often start in the classroom, and I use my studio practice as a way to generate course content and dialogue with my students. That is the good part. I am still learning how to find ‘balance’ though. One of my mentors once told me she thought this was just impossible … that there is never ‘balance’. I find this to be true. I have to be okay with imbalance, with being a better artist some years, or a better partner, or a better parent or daughter. Sometimes your work or loved one or child demands more attention, and we must be flexible, honest, caring, loving. I suppose I am learning to give what I can, and leaning into possible failure, and imperfect imbalance.