We’re open! This past weekend The Fabric of India received its first visitors, and the response has been overwhelming.

Lest you fear our opening means the end of our blogging, be reassured. Following our opening week, The Fabric of India blog will continue to bring you behind-the-scenes perspectives, share the fascinating stories behind the exhibition’s objects, and explore handmade Indian textiles in all their varied forms. We’ll be hosting guest posts by and interviews with textile artists, researchers, designers and more, as well as offering sneak-peaks into the events of the V&A’s India Festival.

To start us off, this week we’ve invited Renuka Reddy, a contemporary chintz-maker, to share with us the story of her search for lost techniques, the challenges she’s faced as a designer-cum-maker, and how the V&A’s collection has inspired her work. Renuka’s studio, Red Tree, is based in Bengaluru.

If only I could time travel…

It was nearly two years after its publication that I got my hands on the book “Chintz: Indian Textiles for the West” written by Rosemary Crill and published by the V&A. I vividly remember my response to the spectacular plates, the desire to make something so beautiful. Little did I know how this reaction would change my life in ways I could not imagine.

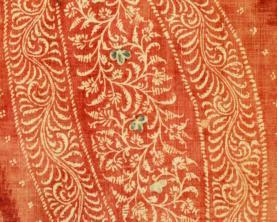

By chintz, I refer to hand-painted resist-and-mordant dyed cottons. I am particularly interested in the intricate resist work of chintz exported from India to the West between the seventeenth and the eighteenth century. This is where I draw my inspiration from.

My goal was to produce chintz, which at that time meant working with craftsmen. So I went in search of one in Machilipatnam and Srikalahasti, two historic towns in the state of Andhra Pradesh where kalamkari (literally ‘pen-work’) is practiced today. I soon realized that the skill and knowledge needed to produce eighteenth-century quality chintz was no longer available. Natural dyes are still used (though often replaced with alizarin and chemical indigo) but more importantly the fineness I was seeking eluded me. The biggest disappointment was that the practice of wax resist was completely lost; no one could remember the technique. This was a huge roadblock. How could I produce chintz without those fine white lines?

Details from a hanging, Coromandel coast, about 1720-50. Museum no. IM.2-1937 © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

I must admit that the unknown was as compelling as the beautiful textiles themselves. It was clear that if I was going to produce chintz, it would have to be hands-on. The cross over from designer/engineer to artisan was a significant change but I’ve discovered painting with a kalam brings its own rewards; stillness in mind and body is essential.

The Wax

My first challenge was to decode the wax resist technique. How could one draw with wax lines that were sometimes finer than those that can be drawn with a pen? Most literature describes this step in a couple of sentences: “This wax may be put on with an iron pencil” from Father Corudoux’s letter on the technique of Indian cotton painting in 1742 and 1747, or Beaulieu’s account in 1734, “Traced with molten wax all the tiny lines that were to remain white. For this purpose he used a specially prepared iron pen”. I assure you it’s not that simple.

I set off to Java, Indonesia, to study Batik Tulis where the resist work is sometimes similar to that of chintz. Not surprisingly, the exact wax recipes were closely guarded secrets. I did learn, however, that a local pine resin and animal fat are added to the wax to increase elasticity and reduce cracking.

Sadly, the finest chanting (wax applicator) I could find was not fine enough. After handling different types of waxes and chantings, I observed that the wax solidified quite quickly. Too quickly to draw fine details, which must take time even for the most expert hand. While the wax works well for flowing lines, I am trying to figure out a way to reduce its melting temperature which would allow me to apply it in a precise pattern. As I continue to experiment with this idea, I also work with a resist concoction made from a combination of natural gums and auxiliaries.

The Dye

When I could draw fine resist lines – though I continue to aspire towards finer lines – I started from step one in the manufacture of chintz, which is the preparation of the fabric with a mordant and buffalo milk. When milk-treated fabric is exposed to sunlight, the high fat content from buffalo milk penetrates deep into the fabric which prevents dyes from spreading. As in most steps involved in making chintz, the results can be unpredictable. It’s difficult to know if the milk has spread evenly and penetrated sufficiently until the first smudge appears, sometimes after weeks of work. I wonder if the addition of UV light or ultrasonic energy would give more consistent results; another entry in my long list of experiments to come. Interestingly, craftsmen in Srikalahasti have begun to use processed milk due to unavailability of fresh buffalo milk. I haven’t had much luck with it, and because buffalo milk is so crucial to my work I have now become a buffalo stalker.

On prepared cloth, the outlines, resist and filling are painted over many steps. Black from fermented iron, yellow from pomegranate, blues from indigo and all the shades in between from a combination of dyes. The source of red color is Indian madder roots – or is it chay roots? To be more precise; Rubia cordifolia or Oldenlandia umbellata? Due to a largely unregulated trade, it is difficult to distinguish if I am buying madder or chay – especially when purchasing dyes in powdered form. Historically, chay was the source of reds/pinks in Coromandel chintz but at some point, madder seems to have been incorporated. Whichever be the case, it is impossible to always predict the outcome when working with natural dyes as there are so many variables to the process. Surprisingly, I find working with alizarin equally challenging despite preparing elaborate swatches.

In between colors and at the end, painted cloth is washed and bleached with cow dung. This I was unprepared for; washing is back-breaking work. In my last trip to Srikalahasti, I met a washerman who I understand is the last person in the community to do washing and cow dung bleaching for local craftsmen. What a privilege it felt meeting him.

With no formal training in natural dyes or secrets passed down through generations whispered in my ear, I started this journey with a clean slate. As frustrating as this can be at times, I find an incredible joy in discovery; in making mistakes only to learn something new, or looking at everyday things and finding new uses for them. For instance, here I must tell you of my latest tool which I have grown quite fond of. In preparing the cloth for drawing, the cloth is recommended to be beaten with a round wooden pestle to make it smooth. This is quite commonly used in North India to wash clothes but is not so common in the South. I’m not a big fan of cricket but this child’s cricket bat was a perfect replacement.

Chintz is an utterly fascinating textile to me for many reasons. It was so popular at one time that Western countries banned its import in fear of economic instability in their local textile trades. And besides causing a revolutionary change in taste and fashion, it is the epitome of artistic and design exchange across cultures and continents. That from an era of such basic existence came a sophistication and technical excellence unmatched to date absolutely amazes me. If only I could time travel and see how it was done for myself.

Thanks to Renuka for sharing her chintz-making journey with us.

An amazing article! I read it firstly because my lovely Great Grandmother adored chintz prints. Secondly it really brought home the sheer production costs of fabrics. I am interested in historical costuming and it’s good to understand just why fabric was so expensive.

I usually find some historical writings and photographs of textile development. This article was the best presented in terms of facts, clarity of writing, and the step by step development of the artist’s research and work.

My great grandmother and grandmother were excellent seamstresses, and created fascinating clothes and blankets/towels (? using beading, embroidery, simple weaving). My vocabulary for 1891-1950 textiles and design is a bit short of explanation.

But my grandmother spoke of “chintz’ when describing her Swedish mother and father’s use of the fabric type. And know little when chintz was used in fashion in the Swedish monarchy before 1870? Identifying chintz seems impossible in the fabric textile books, and the fabric stores. Whether or not the fabric is real “chintz’ since the price is high.

Thanks for this great article. atk

I absolutely adore this article and am highly appreciative of the scholarship and dedication of the writer. I wondered if she looked into the Pysanky drawing tools in terms of small wax drawing hand tools. I look forward to reading more, and seeing more of the work produced. I am inspired to attempt a piece of smaller scaled chintz like work. I am inspired and curious. Thank you

So coool.

The motive remind me about Batik Pekalongan from Indonesia.

Lovely article Renuka…excited to see you and your work soon.

Thank you, Renuka, for sharing your studio with us today and giving us that wonderful demonstration of your process. I think you are going to find yourself written up in textile history books someday. Good luck with your work. Keep experimenting like mad. I just know you are going to discover more and more about this ancient dying process as you continue your experimentations. It’s all so fascinating!