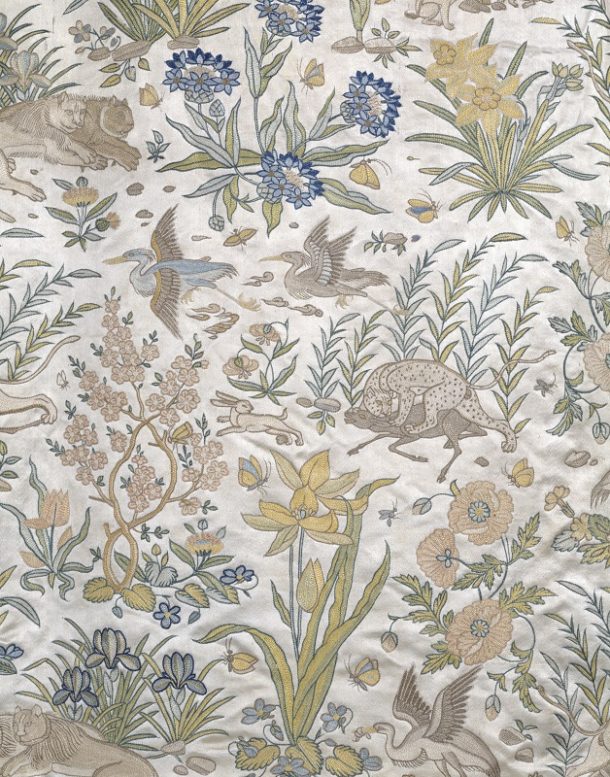

The V&A’s Mughal embroidered coat is well known as one of the finest surviving examples of Indian court dress, and has been frequently displayed and published since the Museum acquired it in 1947. But in spite of its superb quality, the coat was rejected for acquisition by V&A curators not once, but twice.

Its owner was a Mrs W. A. (Beryl) Blake who lived in Yorkshire. Recognising its museum-worthy quality, in 1929 she offered it to the V&A through the National Art-Collections Fund (now The Art Fund). At that time, Mrs Blake considered it to be from Iran and it was referred to as ‘the Persian coat.’ It was shown to the deputy Keeper of Textiles, A.J.B.Wace, a classical archaeologist who had excavated at Mycenae and whose main area of textile expertise was Greek embroidery. In his response to the NACF of 18 October 1929, he wrote ‘The coat is certainly an interesting piece, but at the present moment I hardly think it is the kind of thing we should care to recommend for purchase, and I am not at all sure whether it is Persian; in fact it looks to me more like Indian work.’

In this attribution at least Wace was correct, but it is baffling that he did not think it a suitable piece for the V&A’s collections, whichever culture it belonged to. Wace did not mention his thoughts about the coat’s possible Indian origins to Mrs Blake, instead writing in a short letter to her simply that ‘we do not wish to recommend it for purchase.’

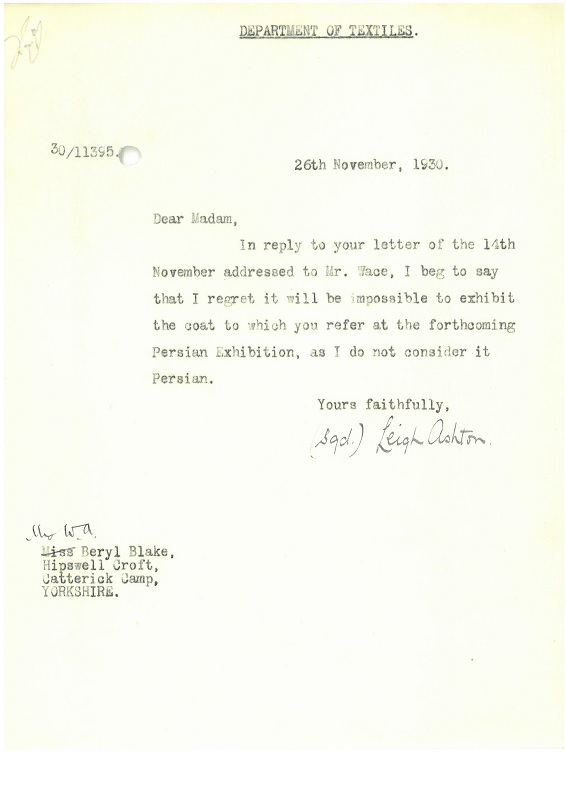

Undeterred, a year later (14 November 1930) Mrs Blake contacted Wace again. She had heard that there was to be a great exhibition of Persian art (which took place at Burlington House in 1931) and once again sent the coat to the V&A with a note saying ‘Here is my Persian coat. It will be very interesting for me if it is exhibited at the Persian Exhibition as I shall then learn more about its history.’ This time the reply came from Leigh Ashton of the Textiles Department (later Sir Leigh Ashton, Director of the V&A 1945-55). In another rather terse letter, Mrs Blake is told ‘I regret it will be impossible to exhibit the coat to which you refer at the forthcoming Persian Exhibition, as I do not consider it Persian.’ There is no suggestion that it might be usefully offered to the V&A’s Indian collection instead.

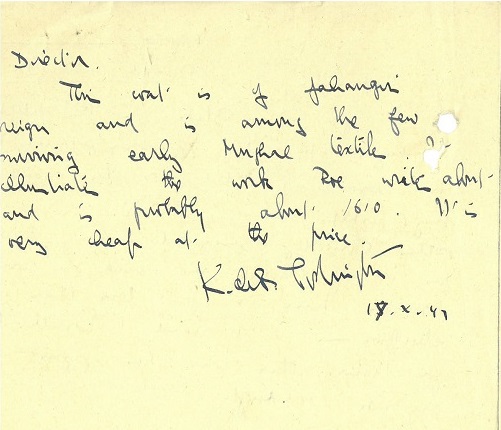

There is now a 17-year gap in the correspondence and one might fear that Mrs Blake had given up and sold the coat, or perhaps given it to another more appreciative museum. But no – in October 1947 it appears that Mrs Blake, now living in Norfolk, has brought the coat in to the V&A again, now in its Indian incarnation. This time, it was shown to the Keeper of the Indian Department, the renowned Indian archaeologist and art historian Kenneth de Burgh Codrington. At last, the coat is recognised for what it undoubtedly is. Codrington writes in an note on the file (in his notoriously terrible handwriting) ‘This coat is of Jahangir’s reign and is among the few surviving early Mughal textiles. It illustrates the work [Thomas] Roe [James I’s ambassador to the Mughal court] writes about and is probably about 1610. It is very cheap at the price.’

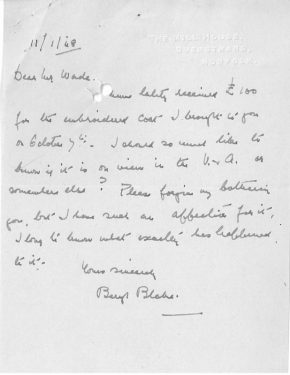

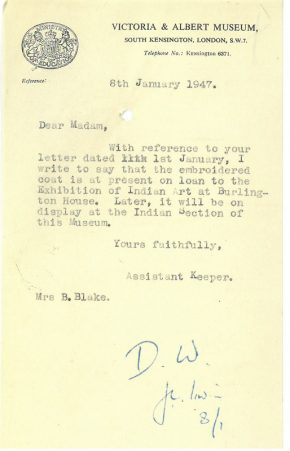

The price was £100. Another note records that Mrs Blake ‘rather timidly suggested asking £100 for it.’ The coat was duly accessioned in 1947, nearly 20 years after it was first offered to the Museum. In early 1948, Mrs Blake, clearly missing her favourite object, writes again in her by now recognisably self-effacing style: ‘I should so much like to know if it is on view in the V&A or somewhere else? Please forgive my bothering you, but I have such an affection for it, I long to know what exactly has happened to it.’ The reply is characteristically terse, this time from J. C. Irwin, Assistant Keeper (later Keeper) in the Indian Section. He tells Mrs Blake that the coat ‘is at present on loan to the Exhibition of Indian Art at Burlington House. Later, it will be on display at the Indian Section of this Museum.’

The landmark exhibition ‘The Art of India and Pakistan,’ directed by Leigh Ashton (who had rejected the coat 17 years earlier), was held to mark India’s Independence and the creation of Pakistan in 1947. The embroidered coat was one of the textiles selected for illustration in the catalogue, and this was its first public appearance. Since then, it has been shown in several other major exhibitions on Mughal art, and is one of our most cherished objects. It will of course be on display in The Fabric of India and we are still learning more about it. Reading the story of its acquisition in the file is a sobering experience. It reminds us as curators of the value of discussing objects with colleagues in other fields to one’s own – something which we are fortunate to be able to do easily at the V&A. Reading Mrs Blake’s letters also brings out in a most poignant way the fact that many museum objects come to us from individuals who are offering their most beloved possessions – and we should be grateful to them for doing so.

I want to thank you for sharing this piece of your organization’s history! First because both historical fashion and Mughal design & decor are of such an interest to me, and because it’s frank in its assessment of the way employees have carried themselves when dealing with art acquisitions. I hate to use the word snobby, but it seems fitting for situations such as these, and too often have I been in contact with curators who turn their nose up and miss out on opportunities to truly appreciate great art. Anyone with eyes can see this is an absolute stunning piece! The way in which Mrs. Blake was treated is discouraging, but what is uplifting is the acknowledgement of that fact and growth from learning it’s not the way to treat art and people who care about art!

man, just give our things back that you looted or took away. the British museum, Victoria albert museum should be known as the collective museum of India and Pakistan. Sigh