Have you ever wondered what an archive contains?

Sometimes the answer is thousands of boxes of paper files – but if we delve a little deeper into the boxes, the contents can be fascinating.

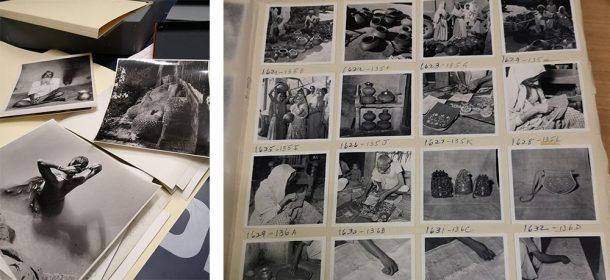

I will share with you my discovery of the ‘Oppi Untracht Associated Material’ photographic archive that I’ve been preparing for the move from Blythe House to the new Collection and Research Centre in East London. While listing more than 4,000 photographs, I learnt a lot about the donor and his lifelong passion for Indian and Nepalese jewellery and metalwork.

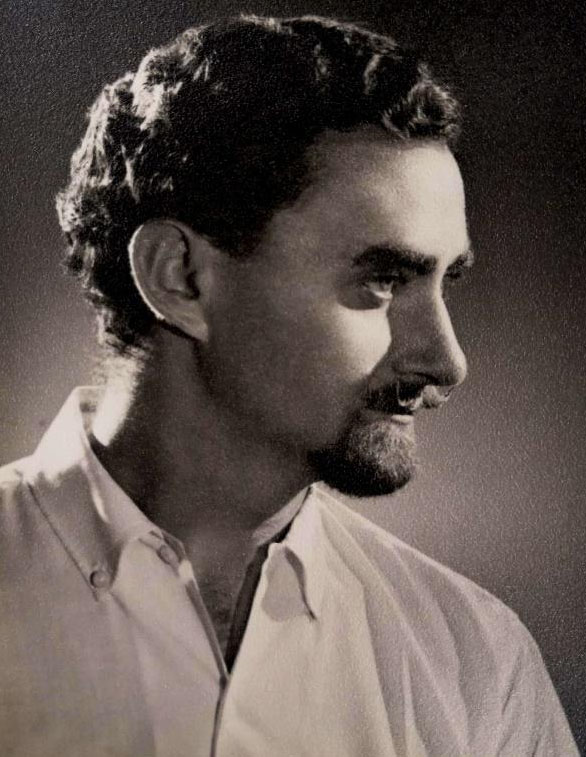

Oppi Untracht (17 November 1922 – 5 July 2008) was a renowned American scholar and photographer from New York who moved to Finland in 1967. He was a jewellery historian, teacher, trained metalworker and jeweller, with a long association with the V&A as a researcher and avid collector. (In this piece, I am going to call the photographer ‘Oppi’ as, after spending so much time with his archive, I began to feel a connection with the creator and his photographs.)

Oppi was a regular visitor to our Indian metalwork collections, which were stored in the basement of the V&A in South Kensington, and friends with several curators who shared his interests. In 1998, he lectured at a conference at the V&A, ‘South Indian Jewellery: Secular and Sacred’.

How did these boxes full of negatives, prints and notes arrive at the V&A?

In 2009, following Oppi’s will, the Untracht’s family bequeathed his enormous and varied collection of objects to international museums.

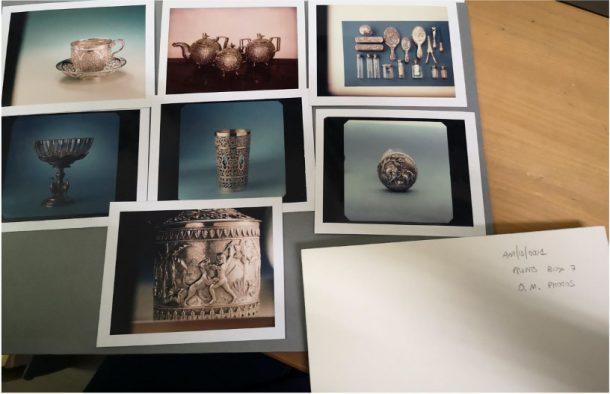

Two curators from the V&A’s Asia Department went to Oppi’s home in Porvoo, Finland, to make the selection from those areas designated by Oppi for the V&A, and they selected a small but very fine group of 17th- and 18th-century metalwork from Nepal collected during field trips in the 1950s and 1960s, and a larger group of 19th and 20th century Indian jewellery. In addition to the objects, the curators brought back more than 4,000 photographic negatives and prints that meticulously record Oppi’s work.

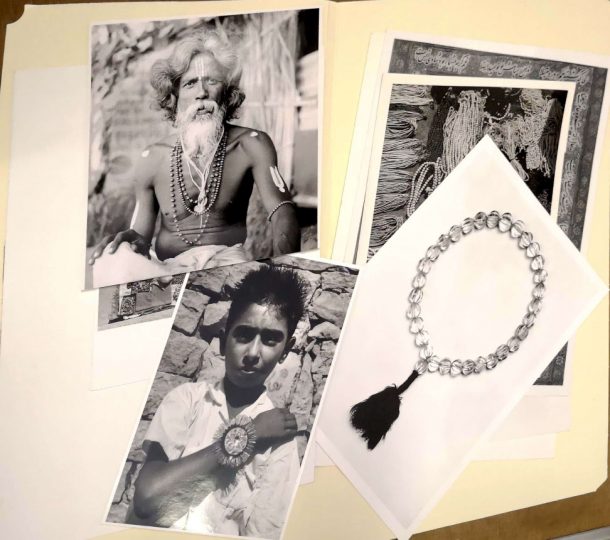

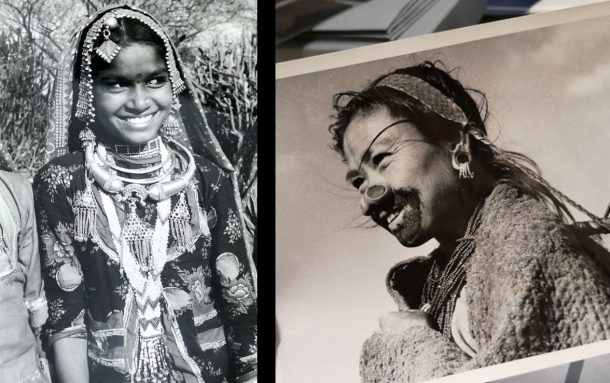

My task was to list the black and white prints and negatives in the archive – I felt like I was travelling with Oppi on his research journey. These photographs document his research travels through India and Nepal, between 1958 and 1973, and his extensive surveys of Indian crafts and their intercultural influences. His interest in Indian jewellery continued over the years, and he made several privately funded trips to India until 2000. As Oppi wrote in his curriculum vitae (which is also in the archive), he wanted ‘to photograph persons wearing fast disappearing traditional jewellery’ and to collect typical examples from Indian private collections.

Looking at the photographs, I was fascinated by the beauty of the necklaces and tribal body ornaments. Oppi was able to capture the symbolic designs worn by the people he met – showing the jewellery in its cultural context. What I found even more interesting were the copious hand-written notes that identify the jewellery names and places of origin, which are an invaluable resource for further studies on the topic.

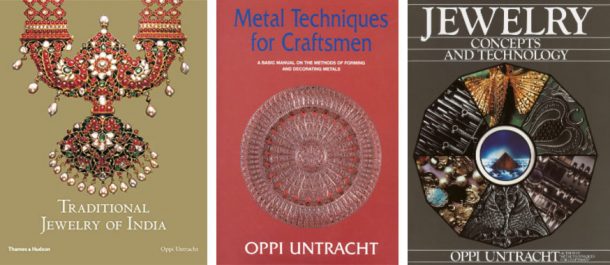

A selection of these photographs was used in Oppi’s renowned publication, Traditional Jewellery of India (1997), which summarises more than 35 years of research and documents and shows more than 5,000 years of Indian jewellery design.

I was not surprised to discover that Oppi was a trained metalworker and jeweller, as his practical expertise is evident in his books. Metal Techniques for Craftsmen (1968) isstill the most comprehensive technical handbook and reference source for metalworkers and, especially, metal conservators across the world. Furthermore, Oppi worked for nearly a decade to write Jewelry Concepts and Technology (1982), a guide that covers the concept behind the ‘jewellery-making mystique’, with detailed descriptions of decoration techniques. With more than 2000 photographs and illustrations, it is still a pioneering book for the field.

The photographs in the archive are unique, and show Oppi’s methodical approach to study. These step-by-step pictures trace the development of ornaments that celebrate the human body. With a cross-cultural analysis, Oppi’s work was able to define the influences of myth and religion, the social structure and economic context of many different communities in which jewellery of exquisite beauty was created.

Almost at the end of my listing work, it was fascinating to discover a more private and personal side to Oppi Untracht. Pictures of Porvoo, in Finland, show his fabulous collections in situ. Oppi’s devotion to his wife Saara Hopea, a Finnish jewellery designer, and their creative-professional bond shines through the pages of his books. As Oppi recalled, she was his best companion on their exciting journeys through India, a ‘dutiful’ research partner, and talented designer behind many of the book illustrations.

I was thrilled to discover that the V&A has some of Saara Hopea-Untracht creations of glass, ceramic and jewellery design. The rings, designed in Finland 1959 – 60, illustrate the Untracht couple’s mutual interest in jewellery-making and their relationship with the V&A.

One final note of interest: Untracht’s real name was Alvin Jacob. ‘Oppi’ was derived from a misspelling made by his little brother, which he then used for his photography. Additionally, ‘oppi’ also means ‘learning’ in Finnish (indeed he was often taken to be a Finn). This little reminder, that we are always learning, feels to me to be a perfectly appropriate name for a researcher of such boundless curiosity.