After working on the Gestetner Collection of paper peepshows at the National Art Library for three years, I find the group of handmade works most intriguing. They all date to the nineteenth century and cover a wide range of subject matters and forms. Although there are only about twenty handmade paper peepshows ( just 5% of the total collection), they all deserve a closer look as each is fascinating in its own unique way. The blog about Maria Graham’s peepshow ‘View from L’Angostura de Paine in Chile’ has already explored one of these handmade paper peepshows in detail. In this article, I will examine some other handmade works that have intrigued me during my research on the collection.

Watercolour drawings

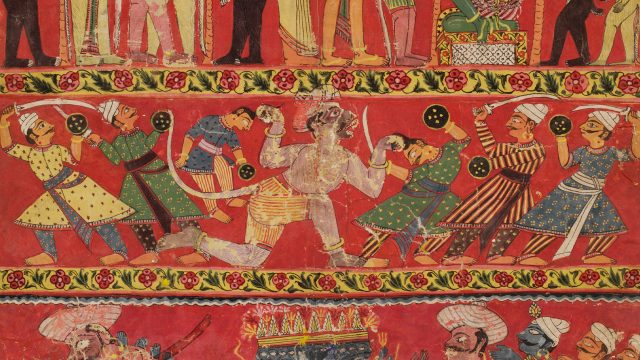

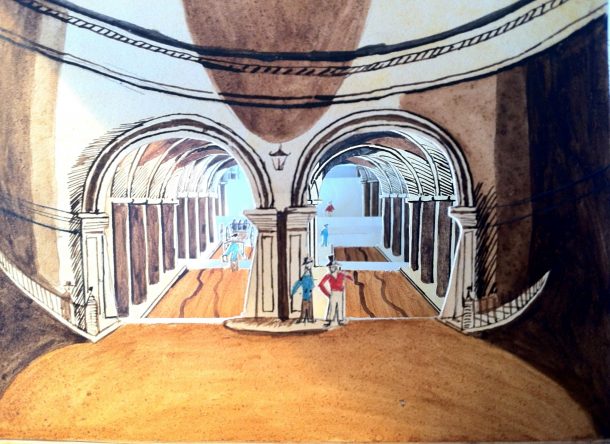

The first type contains those works whose panels are watercolour drawings. Some of them were designed by their makers, and some made after published works. ‘The Thames Tunnel’ (Gestetner 202, ca. 1825; Fig. 1) is an example of the latter. It is a copy of the Thames Tunnel paper peepshow published by T. Brown in 1825 in London (Fig. 2).

The maker spared no effort when drawing the panels, and even faithfully replicated the lamps in the archways depicted in the original work. Brown’s work must have been very popular—we have four handmade pieces copied after this paper peepshow in the collection. Given this object’s fragile nature, it is imaginable that many more handmade copies like Gestetner 202 existed in the nineteenth century.

Yet what makes this example so unique is not its content, but the back of its panels, which bears pencil sketches of a landscape (Fig. 3). Unfortunately, we know little about these delicately executed sketches. Nonetheless, the fact that the card was recycled to make a paper peepshow is important in itself. It seems that the maker was not very concerned with giving the work a polished presentation, which might indicate that s/he treated the homemade peepshow as an insignificant ephemeral, destined to have a short life.

Nineteenth-century Scrapbooking

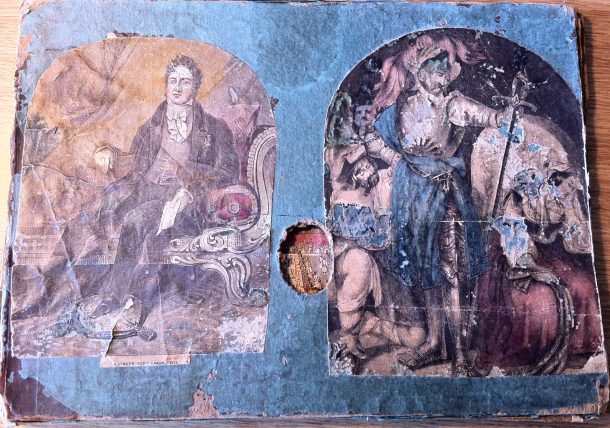

The second category consists of paper peepshows made with print clippings. The idea of cutting and pasting prints may remind us of scrapbooking, and indeed one work can be described as a hybrid between a paper peepshow and a scrap album. In his 2015 catalogue entitled Paper Peepshows: The Jacqueline & Jonathan Gestetner Collection, the late Ralph Hyde named this exceptionally large work ‘Miscellaneous Subjects’ (Gestetner 248, ca. 1845, 125 x 310 mm; Figs 4-5). He certainly could not find a better title to encompass the diverse range of topics represented by the print clippings, which appear to have been taken from illustrated newspapers and periodicals.

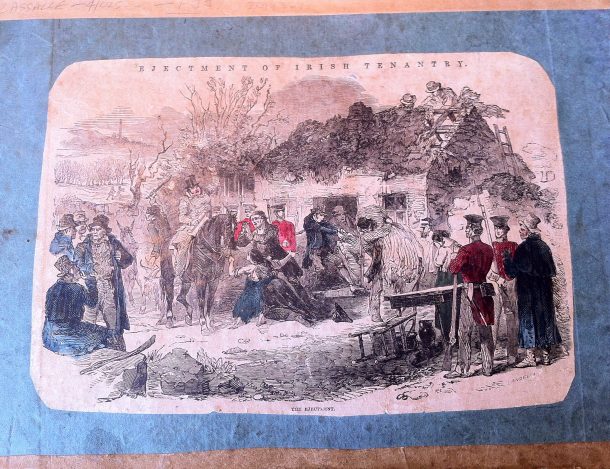

From a portrait of the French king Louis-Philippe to a scene showing Irish tenants being evicted from their ruined cottage (Figs 4-5), this peepshow includes depictions of people from various social strata but gives few clues about the connection between them. Would it be possible that the maker did intend to use the paper peepshow format as a novel way of organising a scrapbook? Was there a hidden narrative behind the juxtaposition of people? With more future research of this work’s provenance, maybe we can get closer to solving the conundrum posed by this paper peepshow.

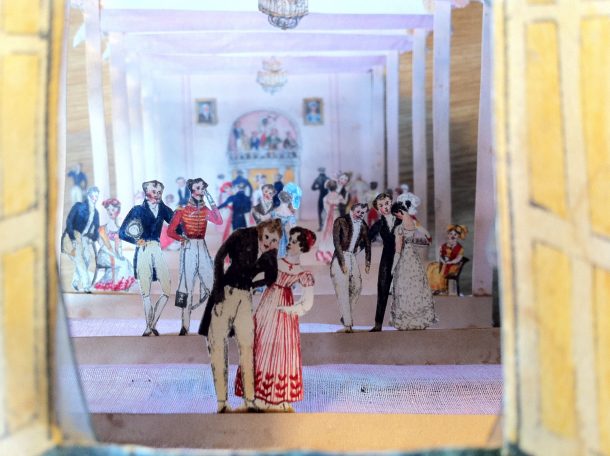

However, not all works made of print clippings have such an incoherent appearance. Gestetner 219 (ca. 1830; Fig. 6), which depicts a colourful ball scene, is an example that lies at the other end of the spectrum. The subject depicted is clear, and the clippings are carefully arranged according to spatial principles. Thus, while there are many dancing couples spread across the panels, none of them is blocked from view when we look through the peep-hole. Moreover, although almost everyone is engaged in dancing, no two figures look the same, with different dress and posture. The small clippings are cut out with much attention, even removing blank space between the legs, etc… Would the maker have bought this peepshow as a ‘make-your-own’ kit, complete with cut out figures and front and back panels to assemble at home? Not enough evidence is available to confirm such a hypothesis at present.

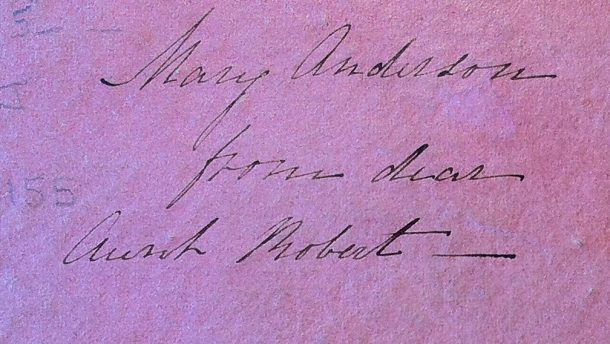

The level of intricacy presented in this work is rare among handmade paper peepshows. On the back of this work, a manuscript inscription indicates that this paper peepshow was a gift for ‘Mary Anderson from dear Aunt Robert’ (Fig. 7). This line allows us precious insight into the production of handmade paper peepshows. The reference to gifting between women, along with the delicate execution of the ball scene, makes it tempting to associate it with the so-called ‘ladies’ work’. This term refers to craftwork by upper- and middle-class women, which was considered a form of showcasing the female makers’ aesthetic taste and artistry, namely, their virtues as well-off women. Needlework is a quintessential example of ladies’ work. Its production required much patience and manual skills, precisely what was expected of a privileged lady. It was common for women to exchange or gift their creations among their circle of female friends and relatives.

Assembling such a paper peepshow was certainly not as difficult as producing a piece of needlework, but could nonetheless be a suitable proof of its maker’s skill. Interestingly, its bellows are not made of paper, but muslin, a luxury fabric often used for needlework in the early nineteenth century. The use of muslin could argue further for the possible association of this paper peepshow with the practice of making ladies’ work.

Handmade paper peepshows are far less consistent in their format, subject matter, or even materials than published works. For that very reason, they often provide insights into aspects of paper peepshows not known to us through commercial works. However, due to the lack of archival sources, we often need to allow room for speculation. But perhaps more importantly, part of our fascination for these handmade works comes from an appreciation of the joy of making. Thanks to artist Clare Bryan, we also can play at making our own paper peepshow. For the exhibition Alice: Curiouser and Curiouser, Clare has prepared a template, which can be downloaded here for free.