With the aim to gauge the breadth and scope of the professional life of Isabel Agnes Cowper, the V&A’s 19th-century female Official Museum Photographer, I have been looking into the circulation of photographs made by her during her 23-year tenure at the Museum (1868 – 1891). This ongoing exercise has uncovered evidence of her work in collections, libraries and archives around the world, inserting Cowper into a vast network of 19th-century image-makers.

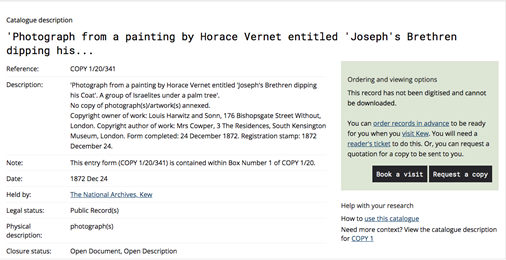

Up until now my research has focused on images originating from the glass negatives Cowper made of museum objects, used as educational tools to extend the reach of the museum’s collection. These frequently turn up as illustrations in South Kensington Museum (renamed the V&A) publications acquired by the international cultural institutions emerging in the late nineteenth century, modelling themselves after the ‘South Kensington System’, a paradigm for art and design education. But a deep dive at the National Archives suggests Cowper’s work also circulated beyond the rarefied ecosystem of museums and institutions to a larger, less elite public community of image consumers. A circulation backed by the retail and wholesale ‘picture dealers’ whose operations often merged the roles of framers, publishers and printers, and who played a major role in the democratisation of the nineteenth century picture market. Evidence of Cowper’s role in this market is supported by the discovery of a nineteenth century document registered at Stationer’s Hall under the Fine Arts Copyright Act of 1862. It reads:

We Louis Harwitz & Sonn of 176 Bishopgate Street, EC1 do hereby certify, That I am entitled to the Copyright in the undermentioned Work; and I hereby require a Memorandum of such Copyright [or the Assignment of such Copyright] to be entered in the Register of Proprietors of Copyright in Paintings, Drawings, and Photographs.

The document goes on to describe the work as:

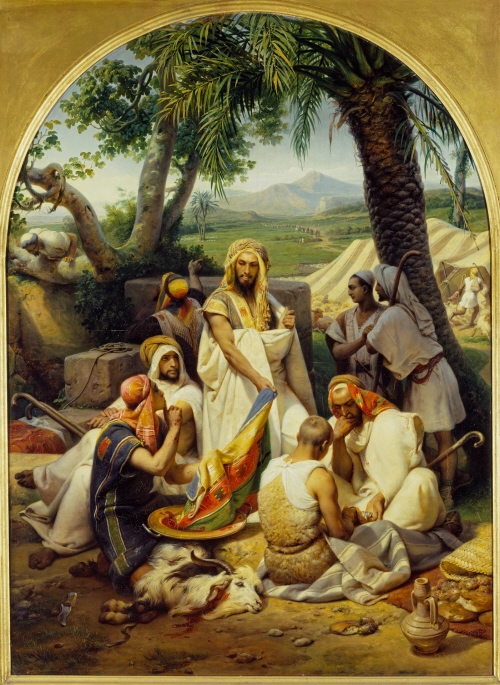

A photograph from a painting by Horace Vernet entitled “Joseph’s Bretheren dipping his Coat”. A group of Israelites under a Palm tree.

Under the column heading: ‘Name and Place of Abode of Author of Work’, it reads:

Mrs Cowper. No. 3 the Residences, South Kensington Museum, London.

It is dated 24 December 1872.

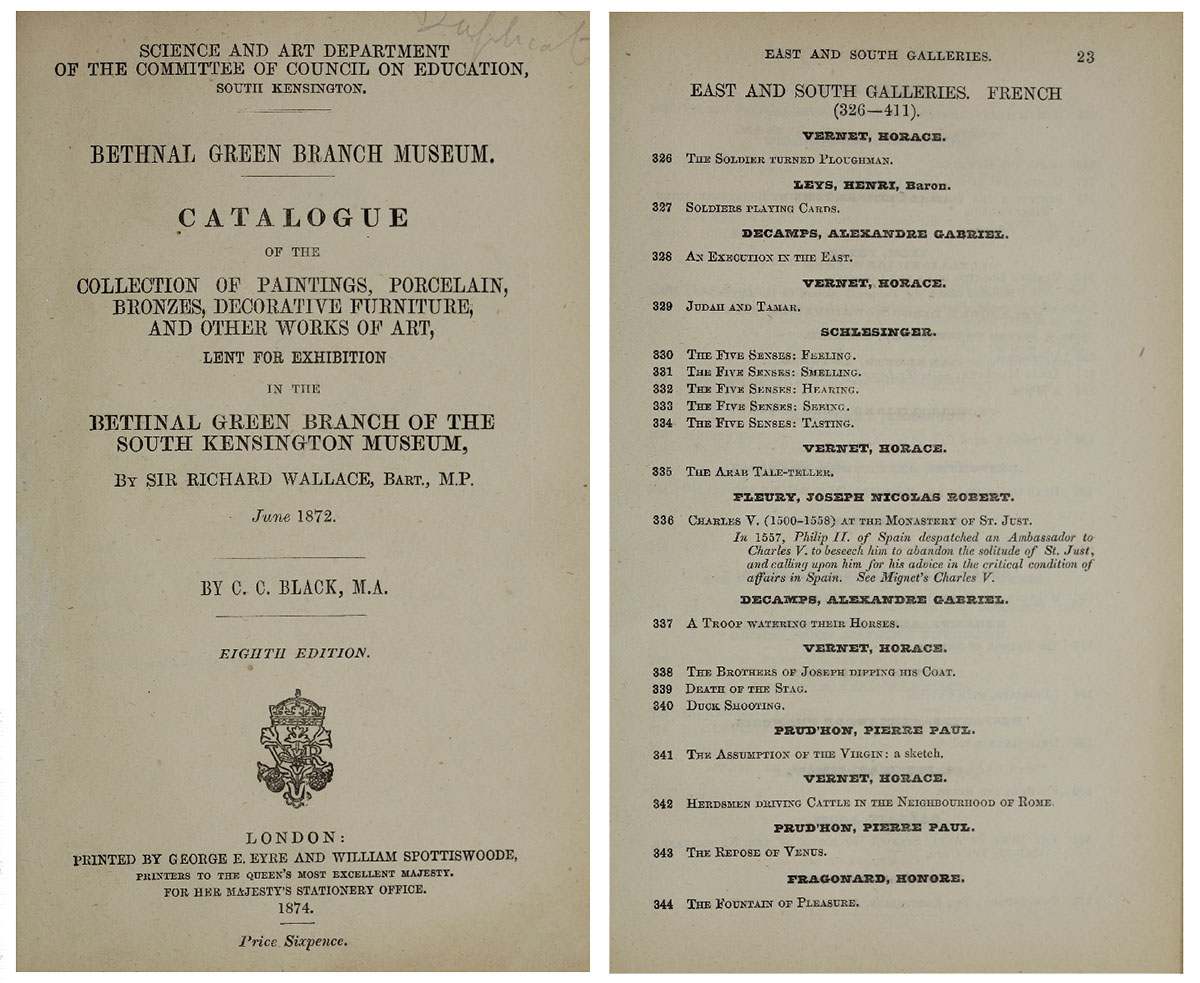

This entry and a similar one immediately following, relate to two paintings by Horace Vernet photographed by Cowper in 1872. An online search identifies these paintings as part of the Sir Richard Wallace Collection, the popular inaugural exhibition at the Bethnal Green Museum in the East End of London, a satellite branch of the SKM that opened in June 1872 and that remained on view through April 1875 while Wallace renovated Hertford House in Manchester Square, the eventual permanent London home of the collection.

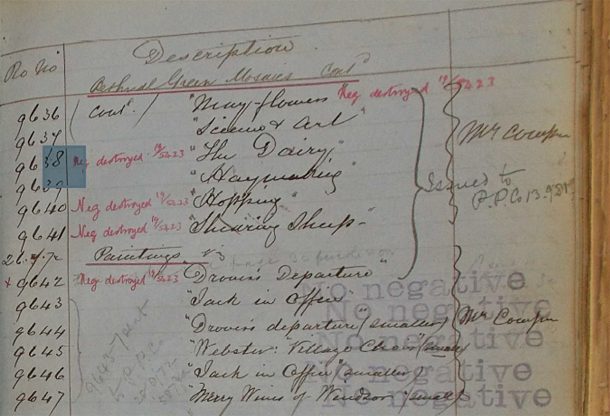

The SKM photography studio archives record many negatives made by Cowper of works in the exhibition, but curiously, they mostly capture furniture and other decorative objects.

Only six photographs of paintings are recorded, and they do not include the Vernet paintings.

This got me thinking about the possibility of Cowper working on her own account, and the significance of her signing over and/or selling the copyright of her photographs to a third party, in this case, to Louis Harwitz & Sonn.

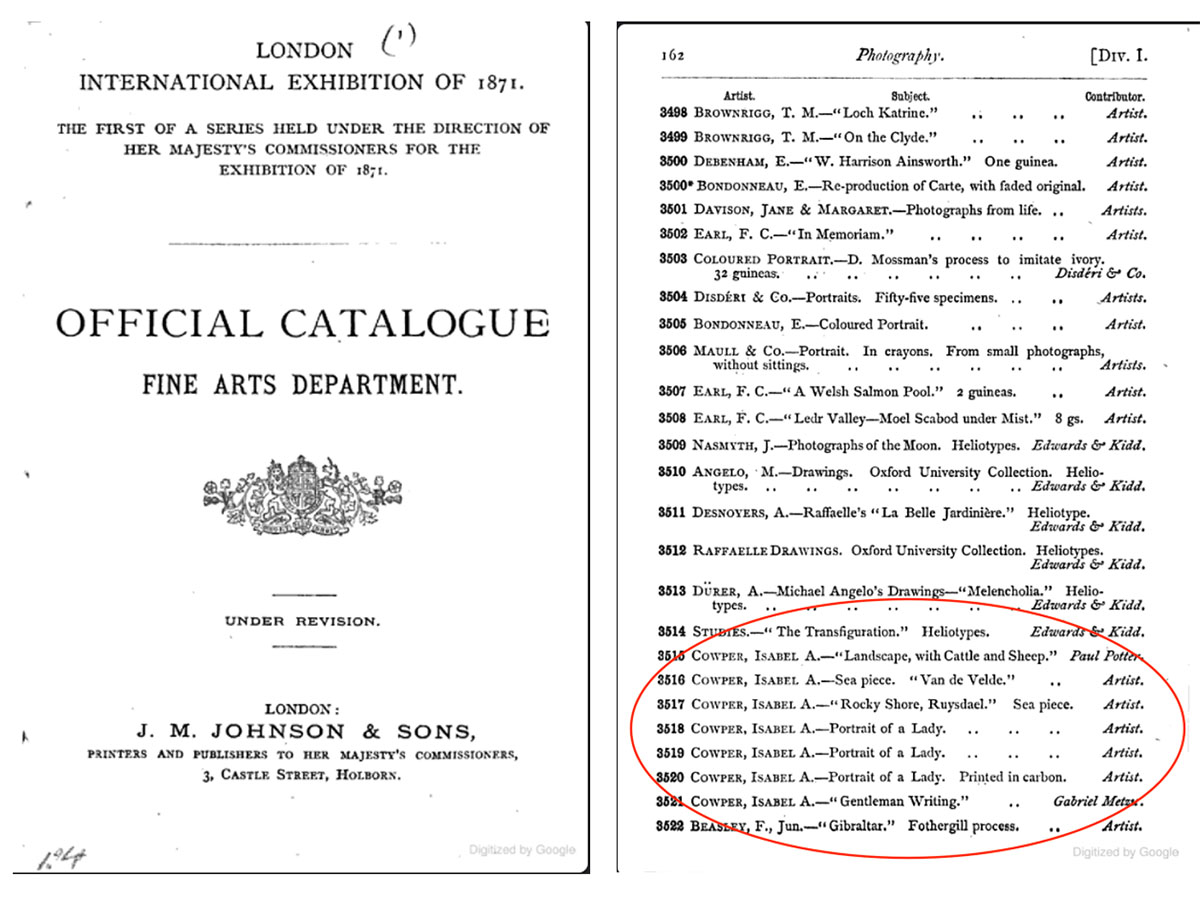

Technically, Cowper was not a museum employee even though she lived on Museum premises with her four children, and produced negatives for the Museum over a period of 23 years. As a woman, Cowper was not eligible to join the Civil Service, a desirable situation available to Cowper’s male colleagues. As such, while for all intents and purposes she was the ‘Official Museum Photographer’ – even describing herself as such in her resignation letter – she remained a freelance employee, her payment on a per piece basis, calculated per square inch of glass negative made. It is interesting to note that during this time Cowper was also exhibiting her photographs under her own name (as opposed to identifying as an agent or employee of the Museum) in the series of international exhibitions held in London at the Royal Albert Hall in the 1870s, suggesting an inclination for self-promotion/economic self-determination that could be interpreted as a response to job insecurity, or an example of entrepreneurial inclination. Whatever the impulse, Cowper was not an outlier. I’ve found similar records relating to works photographed by Cowper’s brother, the SKM’s first Official Museum Photographer, Charles Thurston Thompson, registering the copyright of his photographs of paintings to renowned 19th-century London art dealer and publisher Ernest Gambart.

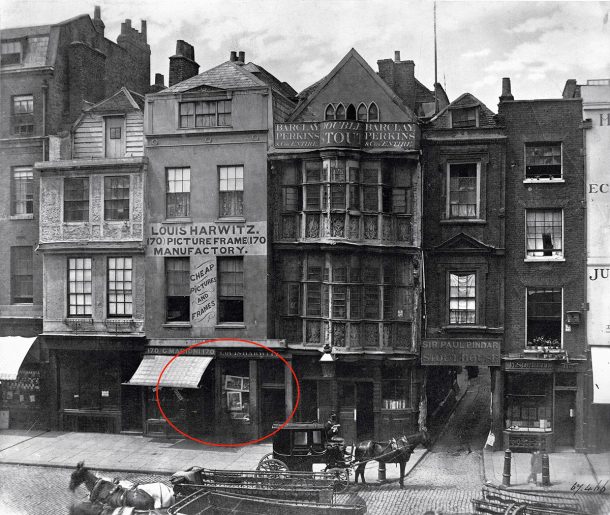

To get a clearer picture into the context of Cowper’s ‘independent’ work, I investigated the scope of the activities of the copyright holder, Louis Harwitz & Sonn. Luckily, from the late 1860s through to the 1870s, the Harwitz shop was located directly adjacent to Sir Paul Pindar’s house, a structure whose façade even in the mid-19th century was already considered an architectural rarity and was frequently recorded in photographs and engravings (when it was torn down in 1890 to make room for the Liverpool Street railway station the façade was acquired by the V&A, one of the largest objects in the collection). The luck came into play when some of these photographs captured the adjacent building and storefront of the framer Louis Harwitz & Sonn.

Here is an image of the Pindar and Harwitz facades taken by photographer William Strudwick as part of his project to record ‘Old London’ (as an aside, this is an example of the small world that was institutional photography. On 24 February 1868, Strudwick, who had worked as a storekeeper in the Museum’s photographic studio in the 1860s, applied for the role of Official Museum Photographer that Cowper had applied for – and took on – on 10 February 1868). The building signage captured in the photograph reads: ‘Louis Harwitz. Picture Frame Manufactory. Cheap Pictures and Frames’. While it is not possible to discern the specific images of the items arrayed in the plate glass window, they are likely examples of the ‘cheap’ pictures advertised.

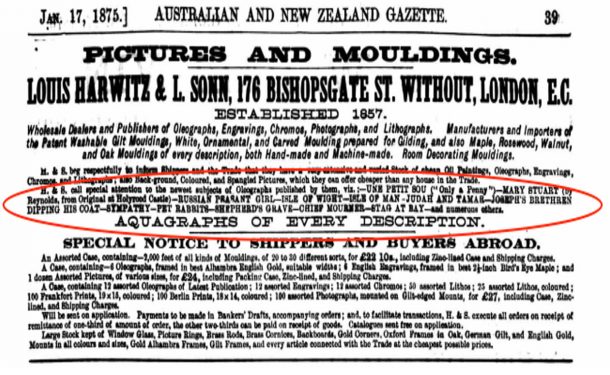

Frequent advertisements placed by Harwitz in national and international newspapers give a more nuanced view of the type of business and the role the framer played in fostering a growing market for the arts beyond the borders of cultural institutions, encouraging the democratisation of the nineteenth century picture market.

This advert placed in a newspaper in published in Australia and New Zealand, and similar ones in national and international newspapers, publicises not only the firm’s manufacture of frames, but also its stock of images sold in bulk, in a variety of formats. In addition to the business of picture framing, Harwitz identifies as:

Wholesale Dealers and Publishers of Oleographs, Engravings, Chromos, Photographs, and Lithographs’.

They offered their stock by the ‘case’ including one set containing:

12 assorted Oleographs of Latest Publications; 12 assorted Engravings; 12 assorted Chromos; 50 assorted Lithos; 25 assorted Lithos, coloured; 100 Frankfurt Prints, 19 x 15, coloured; 100 Berlin Prints, 18 x 14, coloured; 100 assorted Photographs, mounted on Gilt-edge Mounts, for £27…

This particular advert actually specifies the two Vernet paintings photographed by Cowper, referring to them by title only without referencing the artist, suggesting that these images were firmly embedded in the popular imagination after the extended display in Bethnal Green.

The Vernet images are being offered as ‘oleographs’, a type of coloured lithograph, or chromolithograph, textured to resemble an oil painting on canvas. By the 1870s and the introduction of the steam-powered press, this printing process was widely employed to mass reproduce paintings at an affordable price available to a wide audience, becoming a popular form of decoration in middle-class homes. Histories charting the emergence of commercial mass culture identify chromolithography as the amalgam of commercial art and popular culture, transforming art lovers into art buyers. In this advertisement, ‘art lovers’ are being cultivated on the other side of the world.

As Harwitz’s advertisement broadcasts, photographs were one of the many formats that made up their stock of images, and it is not clear if Cowper’s photographs were being sold as photographic stock (mounted on gilt board as advertised) or if they were used by the artisans employed by Harwitz in the process of translating the paintings onto the lithographic stones for printing. In either instance, Cowper’s transfer of her photograph and the accompanying copyright to the framer Louis Harwitz & Sonn represents an example of the creative ways female professional photographers negotiated their careers. At the same time, it situates Cowper within the 19th-century narrative, incited by developments in printing, photography, art training and international trade regarding the commodification of art in the nineteenth century, a commodification that exists in the present day. Here is an example of a trader found online among the numerous dealers of ‘fine art reproductions’. It offers copies of the Vernet painting in various formats, providing a service not unlike that advertised by Louis Harwitz & Sonn and to which Cowper, in her role as photographer, contributed.

I wonder if the lithograph that’s been passed down in my family of Horace Vernet’s Judah and Tamar might have been made by Louis Harwitz. It came “around the horn” to San Francisco after the Gold Rush and was won in a raffle. It has a heavy gilt frame and does not have the arch effect in the sky.