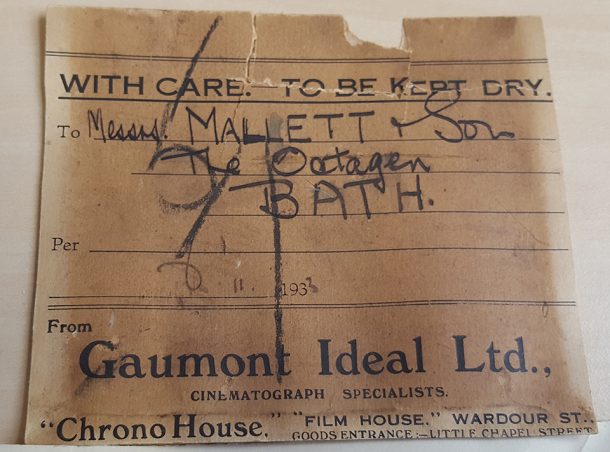

Preparing for a major store move can lead to unusual and exciting discoveries. Last year, while working through crates of old furniture-related records at our Blythe House stores, I found a battered metal box. Inside it were four big film canisters, two marked ‘Chippendale’ and two ‘Sheraton’. A note recorded that they had been given to the Furniture and Woodwork Department in 1973 by the Furniture History Society. The FHS had received them from the Bath antique dealers Mallett & Son. On the box an address label indicated that the film production company Gaumont Ideal had sent them to Malletts in 1933. They had clearly not been viewed for many years, because the V&A does not have facilities for showing 35 mm film.

Thrilled by this discovery, I took them to a viewing room at the British Film Institute (BFI), and was delighted to see that they were charming and atmospheric semi-fictionalised biopics about Thomas Chippendale and Thomas Sheraton, the highly-regarded furniture designers of the 18th and early 19th centuries, and evidently made in the 1920s. Each was a two-reeler about twenty minutes long. It was a wonderful moment for the film about Chippendale to resurface, as 2018 is the tercentenary of his birth, with exhibitions being held at museums and houses across the country.

The scenes were mostly performed on studio sets furnished with antique furniture, but the Chippendale film also included fascinating location filming outside Adelphi Terrace just south of the Strand, London (demolished 1936), at the Royal Society of Arts, and at Harewood House, Yorkshire. The Sheraton film culminated in a contemporary auction scene, with Sheraton furniture achieving high sale prices, shot on location at Christie’s, King Street, London.

Why were the films made?

By lucky chance, the viewer in the next booth at the BFI was silent film historian Tony Fletcher, who was interested to see these new discoveries, and suggested I call down the BFI curator of silent film, Bryony Dixon. She offered to add the films to the BFI National Archive. In return she arranged for us to have digital copies, which has been a huge help by allowing us to share and to watch them in detail to do more detective work.

We are now able to suggest why and when the films were made, although frustratingly we still can’t be certain. Examining the film stock, we found a date code for 1925, and a mark indicating that it was safety film, instead of the usual flammable nitrate film. The use of safety film together with the lack of any front titles or end credits suggest that the films were made for educational use rather than for showing in cinemas.

Published histories of film tend to focus on feature films rather than educational films, and so were of little help, but I then had a stroke of luck. When I visited the Royal Society of Arts, their researcher, Anton Howes, did some online searches, and amazingly, found a report which must be about these films in a newspaper, the Yorkshire Post and Leeds Intelligencer, 29 April 1927. The author mentioned a series of films and lectures about Chippendale and Sheraton held at one of London’s major department stores and concluded ‘I believe some of the Harewood House Chippendale, which was filmed a year or two ago for a London exhibition, is shown’.

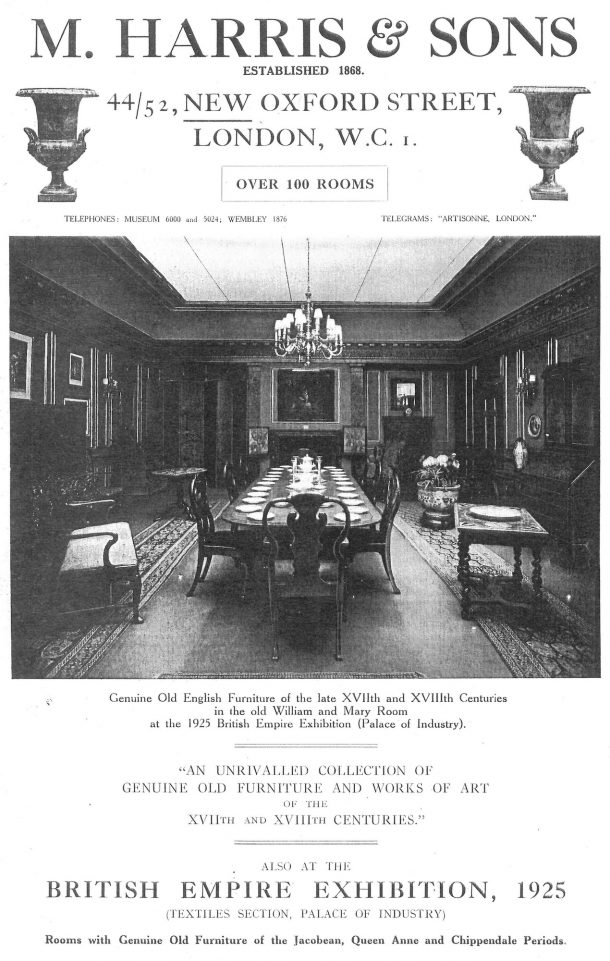

Tony Fletcher suggested that the ‘London exhibition’ might have been the vast British Empire Exhibition in 1924 and 1925 for which Wembley Stadium was first built. He said that Gaumont had made films about British Industries for the exhibition, presumably for one of the pavilions there called the ‘Palace of Industry’. Many prominent antique dealers had stands in the Palace of Industry, and might have been involved in commissioning the Chippendale and Sheraton films.

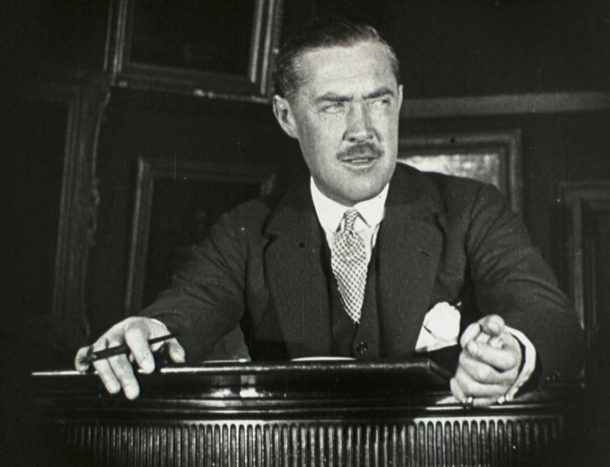

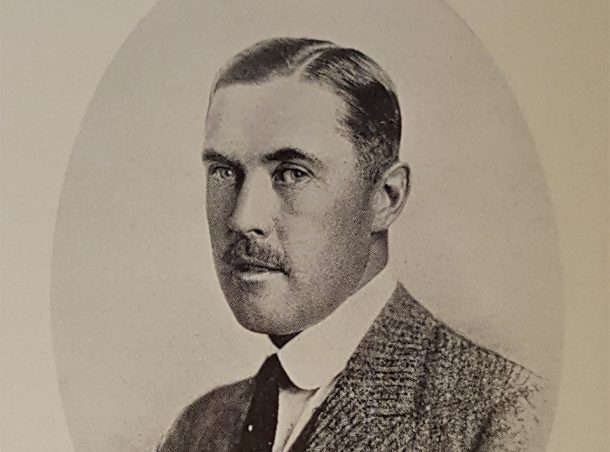

Who were the actors?

Tony also identified the actor playing Chippendale as Humbertson Wright (1876–1953), who began his film career in his forties, and went on to act in over eighty feature films, including several for Gaumont in the 1920s. The other actors in the 18th century scenes may have been stage actors doing a little film work on the side and have not so far been identified.

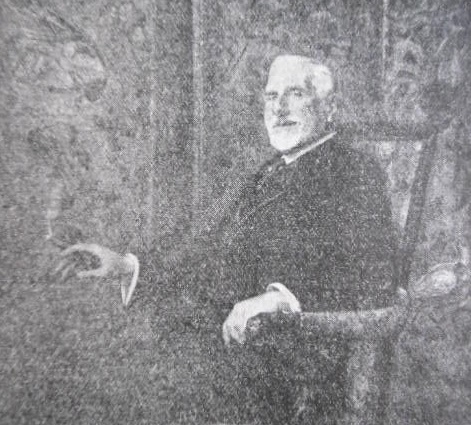

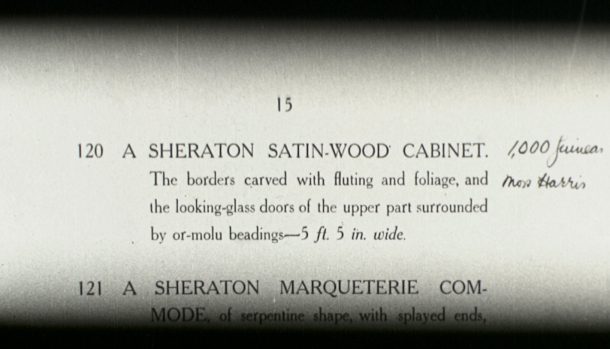

The 1920s auction scene at the end of the Sheraton film includes at least one contemporary London antique dealer. One of the buyers was Moss Harris (1857–1941), who had a stand at the British Empire Exhibition in both 1924 and 1925. Mark Westgarth, a specialist in the history of the British 20th century antiques trade at Leeds University, identified him from a photograph published in 1929. The film shows the auction catalogue annotated with Harris’s name against lot 120, ‘A Sheraton Satin-Wood Cabinet’. Harris’s ownership of the cabinet was confirmed when we found it advertised in one of his firm’s catalogues that must date to 1925-1930.

But while the Christie’s sale looks convincing, it is not clear whether it was genuine or staged, perhaps after a real auction, with fake sale catalogue entries printed up for the film. If the sale was staged for the film, Harris could have supplied the cabinet as a prop. Part of his antiques business involved supplying furniture as props for films and West End plays. Confusingly, in the film Harris bids for a set of chairs rather than the cabinet, an error which probably crept in during editing.

The other dealer noted as a buyer in the Sheraton film was Francis Mallet (d. 1947) of Mallett & Son Ltd, who was probably involved in the filming, although we have not been able to spot him in the crowd. We know from the box label that Malletts later obtained the films, which demonstrates his strong interest.

Another key role in the auction scene is that of the auctioneer. Christie’s archivist Lynda Mcleod has identified him as Charles Agnew, a Christie’s partner who died in 1929, whose portrait still hangs in the archive.

Which historical sources did the film-makers use?

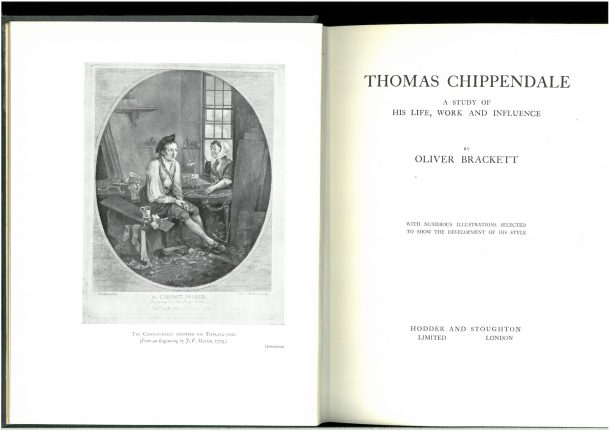

The Chippendale film includes some scenes set in 1760, when Thomas Chippendale was elected a member of the Royal Society of Arts, and others set in 1772, when he carried out two of his best-known commissions: he supplied furniture for the actor David Garrick’s house at Adelphi Terrace, and for Edwin Lascelles at Harewood House. Quite apart from the period charm of the film-making, the film is a fascinating account of the state of Chippendale studies in the 1920s, showing both recent advances in scholarship and the limits of current knowledge. The film-makers clearly based much of it on a recently published biography, Thomas Chippendale, A study of his Life, Work and Influence (1924), by Oliver Brackett. Brackett was a furniture curator at the V&A, who breathed life into a figure about whom previously very little was known. His vivid description of the workshop was translated into live action by the film-makers:

“… the place, as we can imagine it, must have been full of life, the sawing of timber in the yard, the workshops humming with every variety of work, and the energetic Chippendale inspiring his men or rushing to pay homage to some important visitor in the shop”.

Another scene from the film shows the craftsmen taking a break for a drink of beer. This was probably based on the frontispiece of Brackett’s book, an engraving by J.F. Martin, ‘The cabinet-maker enjoying his tippling time’. Brackett describes the cabinet-maker as ‘enjoying his tippling time and [he] seems also to be exchanging chaff with a plain young woman’.

For the narrative of the Sheraton film, the film-makers must have relied on Adam Black’s memoirs (published 1885), which included an eye-witness account of Sheraton’s impoverished life. Black worked for Sheraton briefly in 1804, and later returned to Edinburgh to establish the publishing house A.&C. Black.

Survival

These are the only known copies of the films and it is extremely lucky that they have survived, as about two-thirds of all British silent films have been lost since sound was introduced in about 1930. After that they seemed very old-fashioned and were often sold as scrap by the production companies. Silent films that have survived have usually been in private hands.

Having discovered the films, we were keen to share them as widely as possible. We screened the Chippendale film at the Furniture History Society Symposium in April 2018, and highlights feature in a display of books relating to Chippendale from the National Art Library, ‘Thomas Chippendale Drawings’ (August 2018 – April 2019). A longer article about the films will be published in the forthcoming (2018) issue of Furniture History. Best of all we are delighted to offer them here, courtesy of the BFI National Archive, with new titles and end credits.

Very many thanks to everyone who helped me investigate the films.

All stills from the films are Courtesy of the BFI National Archive.

What a fascinating piece of research, and so interesting to see the role that both serendipity and expertise play in the whole process!

What a fabulous blog post Kate; the films are an amazing survival and it’s a brilliant piece of detective work too! I’m sure it would be possible to find out who the other dealers are at the Christie’s auction – I’m aware of quite a few photos of various BADA events and dinners, and it may be possible to marry up the characters?…anyway, I very much look forward to reading the longer essay in the FHS Journal when it’s out.

Mark

This was fascinating for me to see as Charles Agnew was my grandfather. Sadly I never knew him as he died at the age of 42 when my father was only 13. It was lovely to see the film of him in action at Christie’s.

Thank you for commenting Susie, how good to hear you have been able to see your grandfather on film.