The phonograph knows more about us than we know ourselves

– Thomas Edison, 1888

From the original cylinder-playing phonograph to today’s high-resolution audio files, each generation of listeners has always been able to agree on one thing: the sound was perfect.

In the early years of audio, manufacturers ‘proved’ this perfection via public demonstrations. In a hired theatre a singer – or even an orchestra – would mime to a hidden music-player. At a suitable point in the evening the machine would be revealed to the stunned audience. Recordings had truly matched reality. Again.

More recently the quest for audio perfection has shifted into reverse. Vinyl sales are rising, there’s an open-reel tape revival and even a growing online archive of cylinder recordings. Perhaps the old stuff was better all along?

All of which made me think: what might a ‘perfect’ audio system look like if drawn from the V&A’s own collections? In a previous post I rounded-up our radiograms, but for this exercise I needed to look elsewhere.

My first, and hardest, decision was what to use as the main musical source. An Edison phonograph would have been a bold choice, but unfortunately we only have a cylinder. The streamlined RCA Victor Special was more tempting and shows that by the early 1930s gramophones were mature products that could be styled to dramatic effect. Great for picnics but limited to playing 78s. Not quite what what I was looking for.

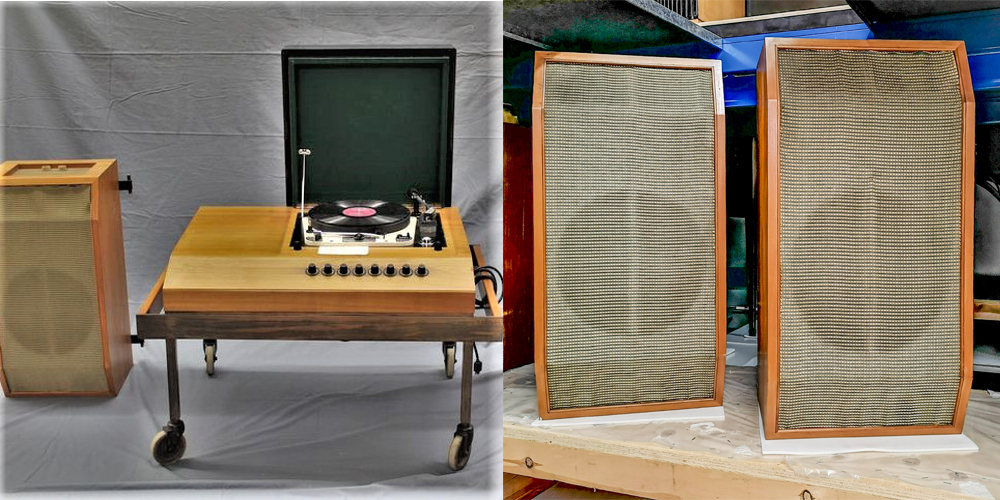

Instead I opted for a Danish Industrial Design Prize winner, Bang & Olufsen’s BeoGram 1202. Hi-fi enthusiasts have long been suspicious of anything that is overly ‘designed’, especially if it sits within an integrated range from the same manufacturer. But this strategy was proving successful for B&O, who in the mid-1960s had decided to look beyond the Danish television and radio market, and target high-end audio customers globally.

The eye-catching 1969 model range was based around the BeoMaster 1200 receiver (a combined radio and amplifier). Customers were then encouraged to add the matching BeoVox speakers, the BeoCord tape recorder and (like me) the BeoGram turntable.

Meanwhile in Cambridgeshire, similar moves were afoot. The Acoustical Manufacturing Co. had already shocked traditionalists by introducing accents of colour to their increasingly modular Quad range. Like its Danish equivalent, Britain’s Design Council was keen to recognise home-grown audio talent and the Quad 33/303 amplifier combination won an award in 1969.

But just a few miles away Lecson Audio were taking things even further. The AC1/AP1 was also a two-box solution – separate pre-amplifier and power amp – but it was the disparate shapes, the radical colour scheme and a complete absence of knobs that took this product to the outer limits of British hi-fi styling. Unlike B&O, Lecson were a tiny operation with much of their budget spent on obsessive testing of sound quality, while all the internal components were hand-soldered by a small group of women working from home. The most modern-looking of products was effectively produced along Arts & Craft principles that William Morris might have approved of (whilst listening to the latest Led Zeppelin album).

Despite this approach, or perhaps because of it, the company had gone bankrupt just before the AC1/AP1 received a Design Council Award in 1974. But it makes it into my system.

Sensing a design-led theme, I picked another Design Council award winner, in the shape of a beautiful pair of Wharfedale Isodynamic headphones. The Yorkshire-based manufacturer said that they’d used a ‘new principle’ in the design which gave a sound as good as rivals costing four times the price. The Design Council judges accepted this claim but were unlikely to have actually tested it.

So just in case, I needed a set of loudspeakers.

From the mid-1920s Celestion manufactured external standalone speakers for radios, promising to deliver ‘the very soul of music’ from their Deco-inspired cabinets. Popular Wireless magazine agreed, describing them as ‘a high class instrument, capable of of high class performances’. Decades later, Ron Arad probably wasn’t too concerned with the reaction of the hi-fi press to his post-modern, post-everything Concrete Stereo (now on display at Design Centre, Shekou). But even exhibition catalogues pointed out that it offered ‘less than high quality sound’. I needed to keep looking.

Leonard Manasseh and architectural partner Ian Baker designed a number of important buildings that married modernist principles with a sensitivity to historical context. But like other busy architects before them, they still found time to design a gorgeous stereo, which was the subject of an article in Architectural Design, January 1961. With that endorsement I picked the speakers to complete my system.

So what have I learned from this exercise?

Long before the Internet there was no shortage of people looking to influence our purchasing decisions. Since World War II state-funded design associations, specialist publications and manufacturers – often working in collaboration – vigorously promoted products that broadly fitted the prevailing modernist agenda, hi-fi included. That started to change with the political, economic and design shifts of the 1980s. The Design Council was significantly down-sized and post-modernism challenged long-standing notions of ‘good design’.

All of which may, or may not, explain why I’ve ended up selecting products that span the golden age of post-war modernism.

If it seems like I’ve drawn some pretty wide-ranging conclusions simply from picking out a few bits of hi-fi, in a future post I’ll dig deeper into the history of the Design Council’s awards scheme and its relationship with the V&A’s collecting policy.

Until then, happy listening.