At the end of March 2019, the display ‘Pietre dure: Highlights from the Rosalinde and Arthur Gilbert Collection’ opened in Gallery 73 of the Gilbert Galleries and is now in place for all to see until December 2020. In this post, we wanted to share our experience of taking the project from idea to installation.

Starting out

The inspiration for the display came from Sir Arthur Gilbert’s wish for the galleries to be changed periodically, so that as many pieces would be seen by the public as possible. It draws together objects recently returned from the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA), those already on display and others from our stores. Excitingly, this meant unpacking crates that had not been opened since the Gilbert Collection moved to the V&A from Somerset House in 2008.

The project began in earnest in early October 2018 and was planned to open on 22 March 2019, in conjunction with a Pietre Dure symposium organised by the Furniture History Society. Over the summer of 2018, Mariam Sonntag, Gilbert Collection Project Conservator, examined and assessed around 50 objects with the support of our technical services team. Inspired by the objects she uncrated, we created a display to share the story of this incredible part of Sir Arthur Gilbert’s collection in the gallery.

Why a display of pietre dure?

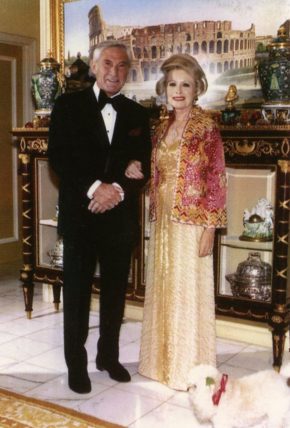

Sir Arthur Gilbert’s collection of pietre dure is revealingly extensive – he acquired examples from almost every major centre of European production. He seems to have been fascinated by the evolution of the technique, its colourful designs and its capacity for rivalling painting in its nuanced rendering of shades and form.

But what is pietre dure? The phrase means ‘hard stones’ in Italian, but is commonly used to refer to commessi di pietre dure, a particular technique that joins together specially cut pieces of hardstone to create larger designs. Although ultimately descended from the ancient mosaic tradition that flourished in the Roman Empire, commessi di pietre dure (to use its full name) refers to the conjoining of hardstones, which is different from traditional mosaic techniques of setting stones on to a ground. One difference you can look for is whether the joins are visible.

This video shows the process of making a pietre dure panel, in this case a reproduction of a section from the Giovanni Battista Foggini cabinet from the Gilbert Collection. Both the panel and cabinet are on display in gallery 73.

How did we select objects?

The process of selecting objects for the display was all about finding a balance, to create an object list that could: fulfil the thematic elements of the display narrative; highlight key examples of techniques and, crucially, be achievable within the time frame and gallery space.

-

Curatorial and Conservation Research

From a thematic point of view, we aimed to draw together a group of objects that could encapsulate the historical, geographical, functional and technical breadth of hardstone mosaics. We wanted to tell the story of pietre dure technique, from its development in late 16th-century Florence under the Grand Dukes of Tuscany, to its diffusion throughout Europe and Russia. We set this within the broader context of the use of hardstones as artistic materials: from the small scale (a carnet-de-bal by Johann Christian Neuber) to large (Florentine and Maltese tables) and from ecclesiastical objects (a tabernacle) to panels later fitted in furniture.

Our selection process was informed by Mariam’s assessments, as she examined the objects’ structures and surfaces to determine which conservation treatments were necessary. Arthur and Rosalinde decorated their villa in Los Angeles with these pieces – using the cabinets to store books, and the desks at which to work.

Even with the occasional signs of use, the collection is in excellent condition. Due to the gallery space and time however, we were limited to selecting just a few examples that could clearly highlight our themes.

One such object we selected provides a contextual cornerstone for the display. It is a framed plaque depicting the Tomb of Cecilia Metella, an ancient Roman site once popular with Grand Tourists. The plaque was created by the Opificio delle Pietre Dure in Florence for Grand Duke of Tuscany, Ferdinando III de’ Medici, in around 1795 – 7. This was the organisation of workshops formed in the 16th century by an earlier Grand Duke of Tuscany, Ferdinando I de’ Medici (r.1587 – 1609). Under his patronage, this was the first major centre of pietre dure production. The plaque in the Gilbert Collection was designed as one in a series of views of Roman monuments, for a room in the Grand Duke’s Palazzo Pitti in Florence. Seized by Napoleon’s army in 1799 and restituted in 1815, the plaque was later given to Pope Pius IX in 1857 as a diplomatic gift.

By contrast, one of the objects we had hoped to display, but couldn’t, was this incredible table top.

The design, with a still-life composition of fruit, flowers and an antique vase, is typical of Florentine private workshop production in the 19th century, but we have recently learnt that the significant cracks running through the black marble were in fact caused by damage from an earthquake in Los Angeles in the 1990s. Unfortunately, the time that it would have taken to consolidate the object made its inclusion impossible. This is not just because of its fragile condition, but also due to a previous repair, which might potentially be removed in favour of a new and subtler solution. This led to discussions about the correct conservation and restoration approach – how much was desirable? Asking ourselves this question, we decided not to display it yet, allowing more time for assessment before we decide upon the best course of action.

-

Practicalities and Layout

As we were installing new objects into specific spaces in the galleries, we had to work with the existing layout, interspersing objects for the display in places which could provide interesting comparisons. Of course this was also informed by practical considerations, such as how the objects would be configured in the galleries, and what the impact of their weight would be on our options for installation – in some cases bespoke mounts would be necessary for support.

We created a visualisation of the gallery to sketch an idea of the display’s layout. Together with our colleagues in the Design team, we then worked out what label holders would need to be produced, and their locations.

The east plinth enabled us to display a table produced by J. Darmanin & Sons in Malta, to demonstrate how the pietre dure technique was adapted outside Italy. The table includes incised borders of decorative shells and coral, creating the effect of relief through carving, rather than using different shades. This is displayed side-by-side with two Florentine tables to demonstrate the technical innovations adopted by different workshops.

A case display entitled ‘Political Grandeur’ groups together smaller-scale objects and gives a flavour of the wider production of works in hardstone and the use of pietre dure techniques.

Some of the examples represent the attempts of rulers to emulate Florentine works; others show how hardstones were used innovatively elsewhere, with makers and patrons eager to produce objects from their own local stone, as well as from traded hardstones and other materials, such as coral. In this section, we decided to include an object from the V&A’s sculpture collection, which had previously been in store. The paperweight is an example of Russian craftsmanship, which made use of the rich mineral deposits in the Ural Mountains.

Produced by the Stebakov factory in 1866 – 7, it was shown at the Universal Exhibition in Paris in 1867 and acquired by the V&A just two years later. The paperweight illustrates a key moment in which the work of Russian workshops reportedly surpassed that of their Florentine counterparts and, together with the ‘Flirtation’ panel, brings the display up to the 19th century.

-

Research and Writing Labels

It can be a long process to write the labels shown in the galleries; to distil information without compromising context. With our list of objects, we began in-depth research in January 2019 into the objects’ technical histories and contexts. After a lot of reading and consultation with external specialists (all of whom are thanked at the end of this post), we shaped our introductory and thematic panels as well as the individual object labels.

So began a long drafting process! We worked closely with both the V&A Interpretation and Design Departments, editing back and forth, and discussing how best for the labels to be edited, printed and designed. Each label has no more than 60 words – a real challenge when one wants to share an object’s history and its role in the display with our visitors!

Mariam organised some key research trips to Potsdam, the workshop of Thomas Greenaway in Towcester, and the Corsi Collection in Oxford, to handle some of the ‘raw materials’ and to learn the techniques first-hand. She also travelled to Florence to visit the Opificio delle Pietre Dure, to find out more.

Today, the institution focuses on preservation and research. The visit included their conservation workshops, archives and the Museo dell’Opificio delle Pietre Dure. Upstairs, the old tools and work benches from the original workshops are on display alongside part of the museum’s extensive library of stone specimens.

This knowledge was crucial in the identification of stones, which was an important focus of the display and subsequent research. The process of label writing was particularly challenging as we entered the tricky field of deciphering which name to call a hardstone – whether to use its historical or present trade names, its geological term, or the name by which it would have been known to the artist. In the end, we decided to take it on a case by case basis, using Mariam’s mappings of the stones (which can be found on Search the Collections) to provide the detail we were unable to include on the labels.

Installation week

Installation week was scheduled for 18 to 22 March 2019. This took place in phases, as many of the objects were at our off-site storage at Blythe House and required transportation. First, objects already in the galleries had to be moved to stores to create space. This of course also meant finding space in our stores through some careful logistics! With the incredible work of the Technical Services team, the objects were assembled and placed in the galleries. The most complicated object to display in the gallery was this large, top-heavy cabinet.

Its installation required 6 technicians, and took around an hour and a half, because of its size and the configuration of its stand.

After dusting the plinths and – with Mariam casting a final eye over each object – the display was finished.

Beyond the display

In addition to the labels in the gallery, we have updated our online catalogue entries. This research is available through Search the Collections, with a new section called ‘Spotlight on Conservation’, which concentrates on technical or conservation aspects relating to the objects. With the expertise of many people, Mariam has created individual stone mappings of the objects, which can also be found on each Search the Collection entry. With only the exception of a couple of objects from the V&A Furniture Collection, this type of mapping is not yet been available online. We hope these give a sense of the rich variety of materials used to make these magnificent pieces.

We hope this post has given you an insight into the process of creating displays at the museum and how collaborative these projects are. It has been a fantastic experience, we are proud of the finished experience for visitors and hope you can see it or perhaps read more about the objects included on our website.

To explore further, you might like the ‘Narrative Zoom’ on the Gilbert Collection website, which focuses on the Tomb of Cecilia Metella plaque.

Over the summer we will be giving some lunchtime tours of the display. These are free and run on a drop-in basis, so please look out for dates on WhatsOn.

Many thanks for that fascinating and helpful explanation of the creative and technical effort needed for such detailed and subtle displays. I always enjoy visiting this gallery, but haven’t yet had chance to experience the Pietre Dure display. When I do, later this year, I’ll post comments on how well it works for me.