A decisive moment

Widely considered one of the twentieth century’s masters of photography, Henri Cartier-Bresson (1908 – 2004) was a pioneer of street photography and a founding partner of Magnum, the international photojournalism agency. The Victoria and Albert Museum (V&A) boasts one of the largest institutional collections of Cartier-Bresson’s work in the world, comprising over 580 gelatin silver photographs. A look back upon the events leading to the museum’s first Cartier-Bresson exhibition reveals the important role the artist played in shaping the V&A’s commitment to photography as a serious art form, and the development of our innovative photography programme.

A major retrospective

In 1968 when the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York considered Cartier-Bresson’s career worthy of a second travelling retrospective, organised by renowned curator John Szarkowski, the V&A’s dedicated photographs curatorial section was still eight years away. It was a time in the V&A’s history, and in the UK in general, when the exhibition culture around photography was nearly non-existent, with few members of the Museum’s senior curatorial rank taking the medium seriously.

This had not always been the case. The V&A’s commitment to photography dates to its founding in 1853, when, as the South Kensington Museum, the institution not only collected photographs but commissioned them for documentary purposes. But by the 1960s, an institutional disregard for contemporary photography had set in. Despite this, curators in the forward-thinking Department of Circulation seized the opportunity to organise a V&A exhibition of Cartier-Bresson’s work, and on 19 March 1969, a major retrospective of the artist’s work opened at the museum. It was the first significant display of a living photographer’s work at the V&A since the 1865 display of work by the celebrated photographer Julia Margaret Cameron. Heralding the opening, the press release unapologetically stated that ‘the connection of the Victoria and Albert Museum with the field of photography… is not known to a wide public’.

Public appetite

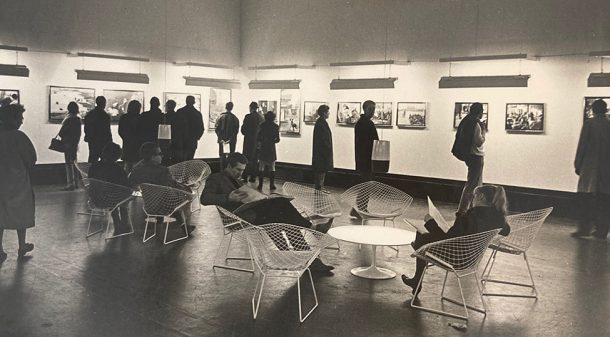

When the V&A’s Cartier-Bresson show finally opened, it was clear that the institutional apathy towards the medium was not shared by the public, with installation views of the time capturing large crowds in the galleries throughout the run of the exhibition.

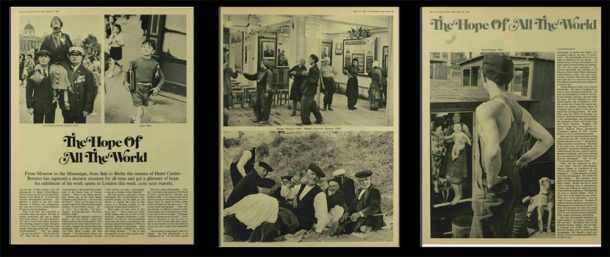

In hindsight, the public’s impassioned response was to be expected. Cartier-Bresson first gained international recognition in 1947 with a retrospective at MoMA arranged by legendary curator Beaumont Newhall. Soon after, in 1952, British audiences were introduced to the photographer’s work when the London Institute of Contemporary Art (ICA) staged a one-person show. That same year saw the publication of the English edition of Cartier-Bresson’s seminal publication The Decisive Moment, a title foregrounding the concept that would come to define the artist’s output.

A changing world

The UK public’s appetite for Cartier-Bresson’s work came at a time when the traditional class and labour roles in the UK were changing beyond recognition. Media attention, increasingly influenced by youth and street culture, shifted focus from the aristocracy to new idols of the era, including actors, writers, musicians and other stars of leisure. Publications such as Life and Look frequently featured Cartier-Bresson’s images, bringing his unique style of reportage into living rooms. The show, and Cartier-Bresson’s notion of the ‘decisive moment’, and the photographic style it embodied, captured this changing world. It was indicative of a broader emerging trend regarding contemporary photography that saw a Cecil Beaton retrospective presented at the National Portrait Gallery, that gallery’s first show devoted to a photographer, and a group show of contemporary photographers at the ICA (inspiring Curator Sue Davies, working there at the time, to establish The Photographers’ Gallery in 1971).

‘Communists and socialists’

Established in 1854, the Department of Circulation, began as a circulating collection of Museum specimens, conceived as a tool to extend the reach of the collections to students at the regional schools of art and design. By the mid-twentieth century, the V&A’s focus had changed, and the Department of Circulation remained as the only department exclusively committed to the Museum’s original educational mandate. Associated with a disdain for elitist hierarchies, the Department fostered an outward gaze that by the mid 1960s nurtured a growing emphasis on contemporary photography for touring, particularly to colleges. So it came to be, according to museum historian Linda Sandino, the Department of Circulation, with a reputation of being staffed ‘full of Communists and socialists’, became the back door through which contemporary photographs entered the collection.

A ‘sober’ display

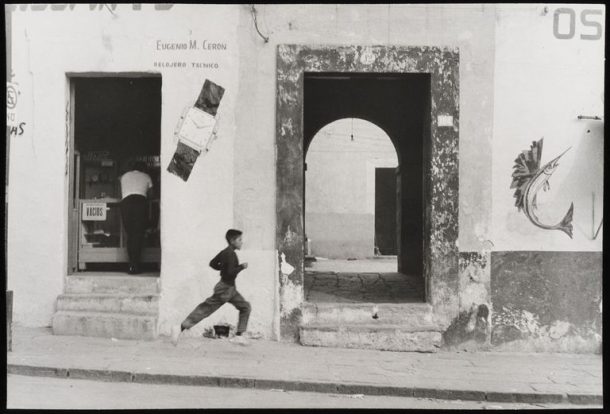

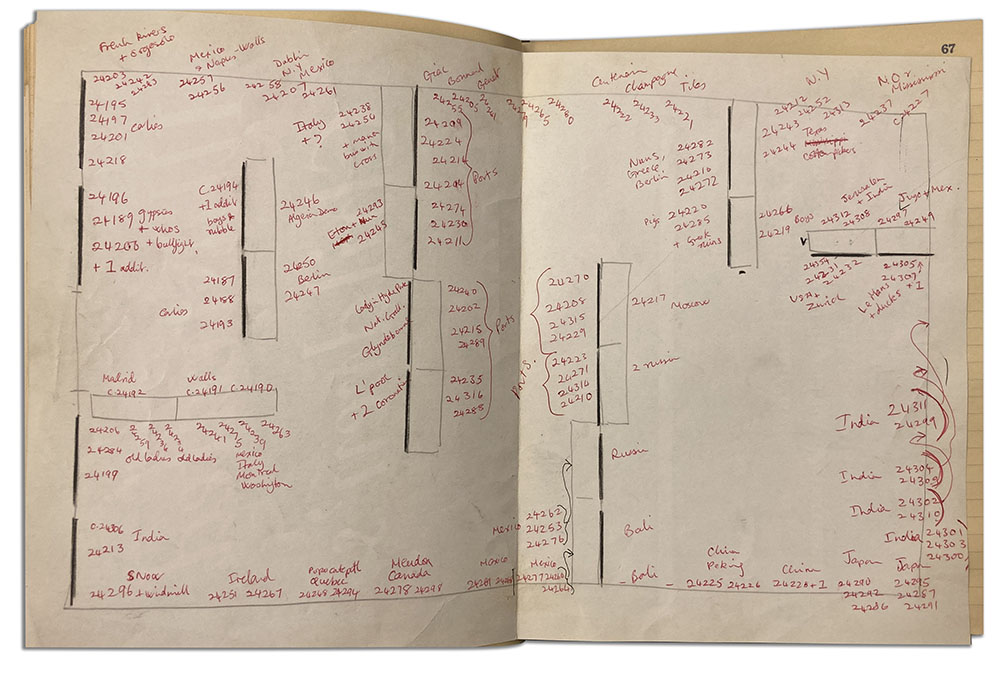

The exhibition was proposed by Carol Hogben, Deputy Keeper in the Department. Once Hogben became aware of Szarkowski’s show, it was suggested that the V&A piggyback on the MoMA selection for practical reasons (including time and expense). The show featured both reportage and portraiture from the beginning of the photographer’s career to 1968, the selection of works closely mirroring, with a few additions, the MoMA show. It was loosely arranged chronologically around themes of geography, featuring works from over 21 countries, mixed in with Cartier-Bresson’s portraits of well-known artists, politicians, philosophers and writers, reflecting the photographer’s expansive take on the modern world.

In a feature published in the Illustrated London News shortly after the show’s opening, Hogben described the display of the 165 gelatin silver works as ‘very sober’, and for its time, it was considered a strikingly spare installation. The black and white works were printed in three sizes and mounted floating in aluminium frames hung at varying heights on the wall. The larger works were installed on either side of freestanding screens, defining a footpath through the show, which Hogben argued was an important part of the ‘exhibition experience’. Smaller works were installed as ‘book equivalents’, set at an angle in trays for closer inspection. In addition to the mounted photographs, 60 images were screened from two projectors. The exhibition remained on view at the V&A for six weeks, and subsequently travelled to Sheffield, York, Leeds and Eastbourne, concluding in Oxford on 30 November 1969 before returning to the V&A, the works eventually acquired as part of the permanent collection.

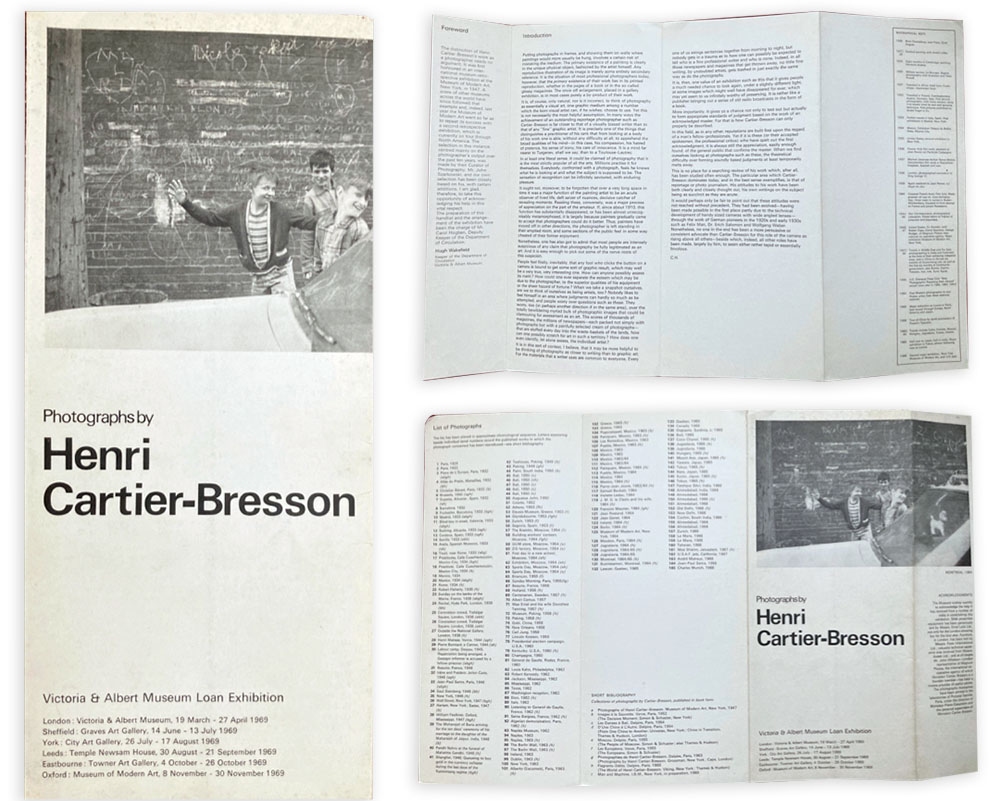

Photographs in frames

The brochure for the exhibition was produced as a folded single card – more a checklist than a catalogue. It included an essay by Hogben, in which he dives right into the fray, opening with an acknowledgement of the ‘risk of … putting photographs in frames, and showing them on walls where painting would more usually be hung’. Risk acknowledged, his argument for photography’s legitimacy begins with a proposal to suspend the association of photography with visual art. To this end, he proclaims the work of Cartier-Bresson to be ‘far closer to that of a visually biased writer than to that of any “fine” graphic artist’, speculating the photographer’s mind as ‘nearer to Turgenev, shall we say, than to Toulouse-Lautrec,’ a notion reinforced by the six texts written by Cartier-Bresson and installed on panels among the works. In conclusion, Hogben doesn’t hold back, inviting viewers to ‘form appropriate standards of judgment based on the work of an acknowledged master. For that is how Cartier-Bresson can only properly be described.’

A national collection of photography

The V&A’s 1969 Cartier-Bresson exhibition and subsequent acquisition, and the passionate response from the public, heralded the V&A’s renewed commitment to the medium of photography, paving the way for the establishment, in 1977, of the UK’s National Collection of Photography. With photography finally landing a dedicated home at the V&A, one of the first acquisitions made by Mark Haworth-Booth, the collection’s first curator, was a group of 390 additional photographs by Cartier-Bresson chosen by the photographer, one of only four such sets made. These two groups of photographs, as well some smaller acquisitions, make up the V&A’s Cartier-Bresson collection.

The importance of this exhibition for the careers of a generation of British photographers cannot be overstated. James Ravilious (1939 – 1999), originally trained as a painter, stated he was inspired to take up photography by ‘visiting the 1969 Henri Cartier-Bresson exhibition at the V&A’, forming a direct line between the V&A’s exhibition and Ravilious’s life’s work documenting the people and landscape of North Devon. For many photographers like Chris Killip (1946 – 2020), who in 1989 became the first recipient of the prestigious Fondation Henri Cartier-Bresson award (judged by MoMA’s Szarkowski), Tony Ray-Jones (1941 – 1972), whose own work was shown at the ICA at the same time as the V&A’s Cartier-Bresson show and Dorothy Bohm (among many others), Cartier-Bresson’s unique vision had long been acknowledged and admired; the V&A exhibition validated their endorsement.

The trailblazing art of Cartier-Bresson championed in 1969 by the Department of Circulation awakened the V&A’s latent advocacy of the medium. Today, in the 21st century, the photographs collection continues to expand. With the historic 2017 transfer of the collection of the Royal Photographic Society to the V&A, the Museum’s collection today ranks as one of the most significant collections of historical and contemporary photography in the world. The imminent unveiling of the expanded Photography Centre is representative of the institution’s ongoing commitment to fostering public engagement with photography through an innovative programme of collecting, exhibition and education.

So glad to have found a record of this exhibition since it made a real impact on me in 1969 when I was at the Central. I still have a print of this famous Venice shot in my studio. Venice was the Ruskin influence which permeated strategy unknown to us students at the time. That I should end up living in a house last occupied by a founder of the cinema ( lived here 1940-61) is quite bizarre. Wonder why ‘Shooting the Past’ has not been shown recently but then wonder how imagery is used for everything now. ‘Heimat’ was a revelation to me over one weekend in the old Arts Cinema Cambridge. However we are living proof of the mish -mash of ideas that contributed to the Art Schools being blamed for a revolution that has been long in the making. Those who used to do also taught us as part of their role in life. Art is not an academic subject even though in 1971 our degrees were abolished – to go metric in Europe also meant industrializing many skills. I was taught philosophy as part of my Dip AD course- as well as Film Studies. It was a higher degree, not a vocational, we could buy our BA’s for £13 as I remember. Never did myself. Thanks for your delving.

Glad to see the date of this exhibition recorded. So it seems I was 13 when I saw it. It started a lifelong obsession with B/W photography.