The judges of this year’s V&A Illustration Awards praised Nora Krug’s courageous exploration of her family history. Nora Krug grew up as a second-generation German after the end of the second world war, struggling with a profound ambivalence towards her country’s recent past. Her book, Heimat (published by Particular Books in 2018), visually documents her search for cultural identity and the meaning of home. By combining archival material such as photographs and written documents with hand drawn illustrations, the judges felt that the book was both original and captivating in it’s interpretation of a very painful and difficult subject.

Heimat has been remarkably successful and in the midst of a busy book tour, Nora took some time out to answer a few questions:

What inspired you to become an illustrator?

I became an illustrator via some detours. I attended a Middle and High School with a special focus on classical music, but I had many interests in other creative fields. After graduating from High School, I studied Performance Design at the Liverpool Institute for Performing Arts, a highly inter-disciplinary school where I was able to channel my various interests into creative projects. My final project ended up being a documentary film about post-war Sarajevo. I moved on to study Visual Communication at the University of Arts Berlin, where I focused on documentary film and illustration, mostly because of the teachers there whose work inspired me. At the end of my time in Berlin, I finally decided to focus on illustration full-time and moved to New York City to study in the MFA Illustration as a Visual Essay program at the School of Visual Arts.

This varied background has continued to impact my thinking as an illustrator in that to me, the act of drawing, the medium or the technique, is not the centre of my work, instead I see drawing as a tool to explore concepts, ideas and themes, and to communicate ideas about the world. What exact medium or visual aesthetic I use is therefore determined by what kind of story I want to tell, or what kind of emotion the subject calls for.

Drawing, to me, means observing, documenting, and reflecting the world around us, in an attempt to understand it better. What interests me most about illustration as a medium is its political potential. Illustrations have always reflected our need to position ourselves in society – and in its most extreme negative, our attempts to propagate ideas that marginalize minorities. As an illustrator, I reflect a lot on this important history of my particular medium, and when I work, I think about the political responsibility we have as illustrators, and I ask myself what we can do to contribute to dismantle these kinds of cultural stereotypes, and to perhaps provide new entry points for understanding political ideas and perspectives.

You have used both archival material and illustration to document your family history in Heimat. Can you talk us through your process?

I spent two years researching my hometown’s and my family’s history under the Nazi Regime, and exploring what German cultural identity means to me. I then spent another two years just writing, and, when I was certain that I had figured out the narrative arch, began with the process of illustrating, which took me another two yeas.

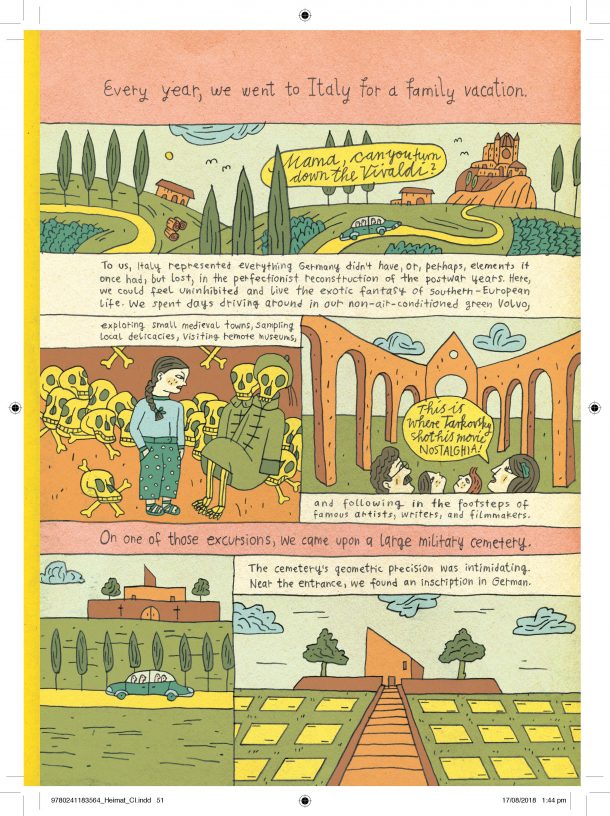

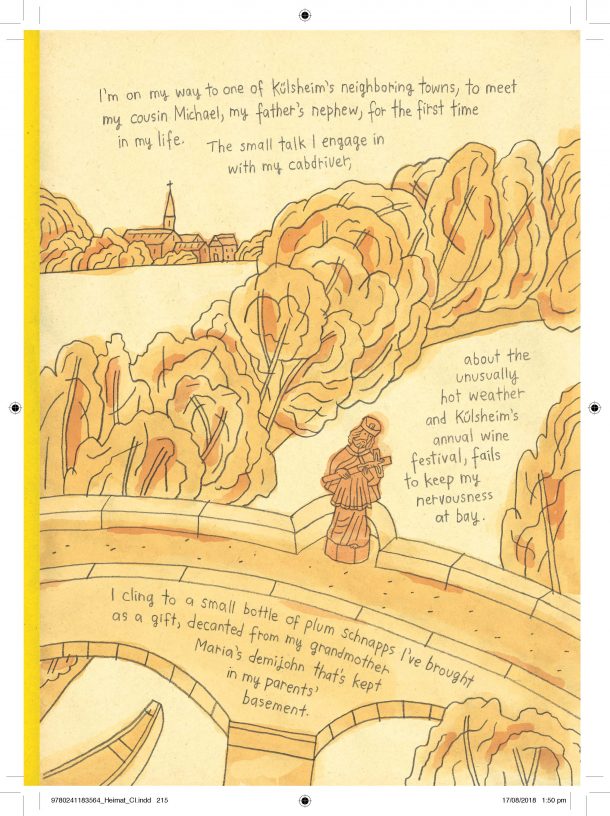

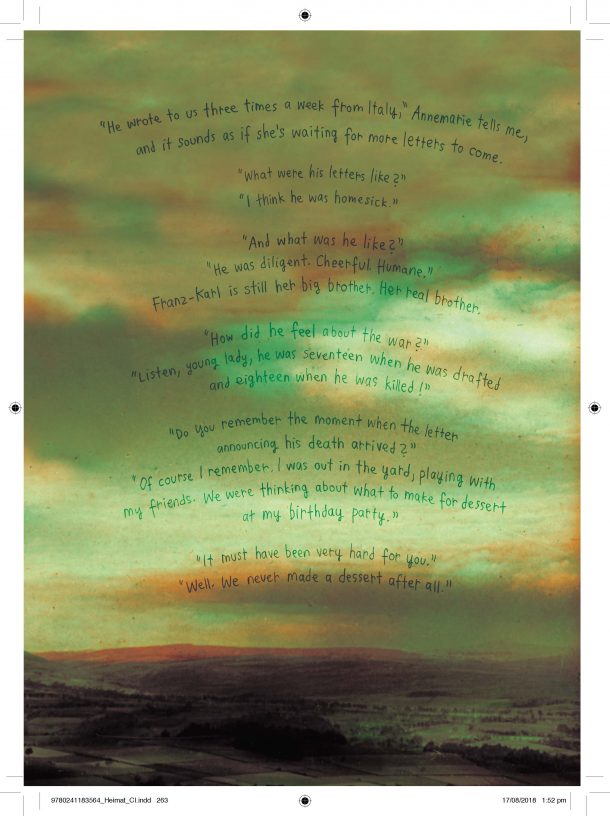

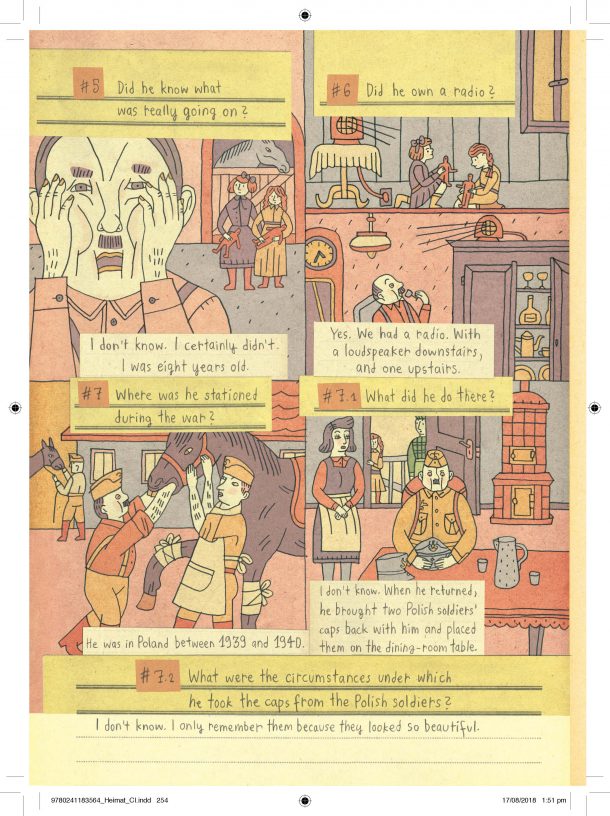

I knew from the beginning that I wanted to move away from the “traditional” graphic novel format (i.e. a set grid of panels and speech bubbles) and approach the subject from a collage / scrapbook angle, partly because I wanted to free myself from making myself the visual protagonist of the book, and also because I wanted to convey the idea of fragmentation. While working on the book, I often thought about the fragmentary nature of memory, and of how the memory of WWII evolves over generations, about how it is informed by and at the same time informs our families and the places where we grow up. History is an accumulation of fragmentary, experienced moments in time to which we assign a narrative in retrospect, in order to make sense of the events that occurred and the ways in which they impact our lives. I tried to capture the fragmentary logic of memory through the visual style I used. Working with graphic materials and photographs also allowed me to integrate some of the documents I myself came upon at the archive – historic evidence that, I feel, can provide direct, physical access into the past in a much more direct way than if I had visually translated them into my own words and illustrations.

How did libraries and archive collections inform your research?

During the two years I spent researching for the project, I reflected a lot on the ways in which we experience and subsequently construct and reconstruct our understanding of history and war. Combining text with illustrations, photographs and visual materials found online or at archives, flea markets, household liquidation stores and in attics and old cabinets in my family’s homes, helped me contrast the documentary with the imagined, the factual with the poetic, and to create a narrative tension that emphasizes the complexity of the German war experience. Picture research was thus not only at the center of the research process for this project, but it also represents the actual conceptual makeup of the book, as the found images themselves move the narrative forward and provide an added dimension for the emotional understanding of war and cultural identity.

My research took a variety of forms. Throughout the research process, I scavenged in flea markets and household liquidation stores for pictures that would provide me with clues to the cultural identity that I feel that I have lost. I looked for recurring visual motifs, hoping they would offer insights into subjects that have occupied the German mindset over decades. I also scavenged in flea markets and household liquidation stores across Germany for visual materials that would provide me with the tangible and evidential understanding of WWII and life under the Nazi regime which my own family wasn’t able to provide me with. Rather than propagandistic material, I focused on items that were created by individuals, objects carrying traces of use, things one would have carried in one’s pocket or glued into one’s family scrapbook, relics that provided a more intimate glance at our history.

In order to look for any visual evidence that would tell me something about my family’s life under the Nazi regime – a photo, an object, a letter, the tiniest scrap of paper – I visited both archives in my hometown and the village where my father was from. I decided to visually embed the materials I found at these archives into my illustrations as they helped me reconstruct the narrative of my family members’ lives and because I wanted to convey the eerie sense of emotional proximity and oftentimes uncomfortable immediacy with which they evoked my own family’s physical presence. Equally important were those materials that provided visual insights into how the Nazi regime’s ideology seeped into the everyday fabric of my hometown and the village where my father was from. I looked at over 800 photos taken of civilians in my hometown between 1933 and 1945, dreading to find my family members’ faces somewhere among the cheering crowds, as their participation in the boycott of the Jewish shops, the celebration of Adolf Hitler’s birthday, or the welcoming of the Führer passing by in his car would have more clearly revealed their political point of view to me.

In an attempt to understand the very moment that the guilt (which I grew into as a German) first set in, I felt that I needed to look at images that would capture the site of disillusionment that marked our country’s historic turning point. I searched the photo collections of Holocaust museum archives across the U.S. and England for photographs depicting the “zero hour”. In an endeavor to bridge the present with the past, in my book, I juxtapose these historic photographs with images that represent my contemporary reflections on the lasting effect that the atrocities we committed has had on our people.

I chose early on to understand Heimat as a passive portrait, because I wanted to avoid referencing my emotions in the images too directly. I felt that using photographs of German landscapes would both document my search for cultural identity and help express the emotions I felt during moments that were challenging. At times when I talked about my own feelings regarding my family’s wartime loss, I felt that I needed to work with landscapes that conveyed emotion without a sense of sentimentality – something that would have been highly inappropriate for a book about the German war experience. Some of these photographs were taken from German flea markets, others from German postcards of the first half of the 20th century that I purchased on Ebay.

In its essence, the act of drawing to me is a visual research process, as it allows me to make historic events and processes visible. By illustrating my family’s stories and memories, I can picture more clearly the situations they found themselves in during the war, while I test the limits of my own empathy towards the decisions they made.

Your work has received critical acclaim and won a number of awards, what advice would you give to students and emerging illustrators? What advice would you give to illustrators that aspire to have their work published?

There is no secret recipe for success. Do the kind of work you are passionate about, not the kind of work you think is going to be most successful. Focus on subjects that you care deeply about, and try to put your personal perspective into every piece you create, no matter if it’s a personal or a commercial piece. Challenge and expand existing ideas we have about what the field should look like. Believe in yourself, but always question what you do. Think of yourself as an author; someone might be able to copy your style, but nobody can communicate ideas or tell a story the way you can. Be supportive of your peers’ work – even though being an illustrator can be a lonely undertaking, the importance that this tight-knit community has for you and the ways in which it might inspire and influence your career should be something to be aware of. Understand the political impact your work as an illustrator has, as your work will always communicate something about the place and time you live in, whether you’re aware of that or not.

Visit this year’s winning entries at the V&A Illustration Awards 2019 display. On until Sunday 25 August 2019.

Hear from our other winners on the V&A blog over the coming weeks.