Carter Jackson, University of York MA research placement and guest blogger, examines architect William Eden Nesfield’s creative responses to various design challenges during the construction of Kinmel Hall nearly 150 years ago.

Over the summer I catalogued the V&A’s collection of construction drawings for Kinmel Hall, a once-magnificent French chateau style country house designed by William Eden Nesfield that has fallen victim to fire and neglect. The extravagant house (nicknamed the ‘Welsh Versailles’) was built for Hugh Robert Hughes from 1871 – 6, and it has recently attracted a series of would-be buyers who have each abandoned plans for its redevelopment. This is due in large part to the inherent incompatibility of adapting a 19th century country house to 21st century needs. While examining the house’s construction drawings, I began to realise that a comparable set of incompatibilities challenged its architect during its construction and resulted in a series of creative design decisions that define Kinmel Hall today. This post examines some of the most intriguing architectural challenges and incompatibilities that its construction drawings reveal.

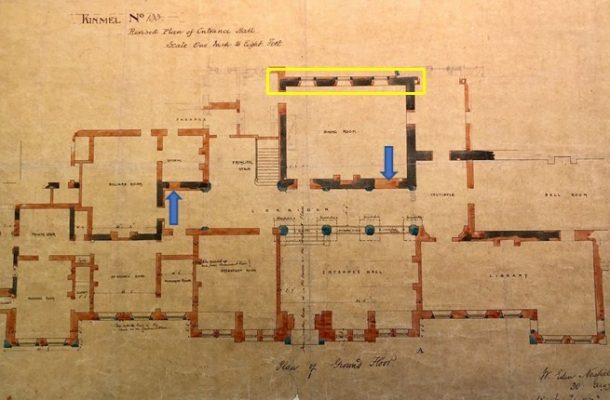

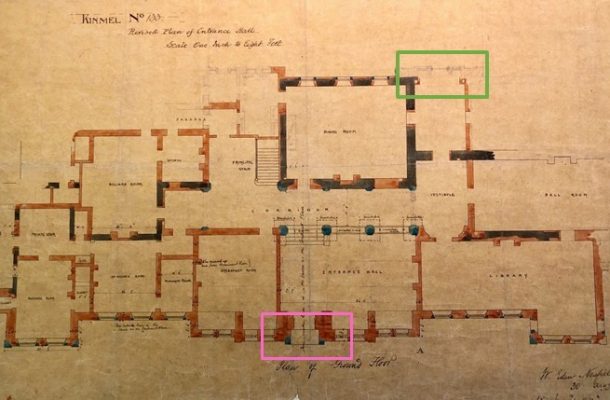

After H.R. Hughes inherited Kinmel from his uncle in 1852, he aspired to build a monumental house on the estate that combined elements of Christopher Wren’s additions to Hampton Court Palace with the exuberance of a French chateau. As architect W.E. Nesfield’s first response to his client’s requests was overly enthusiastic; it was refused for being too expensive and had to be reduced. This underlying squabble of economy versus luxury formed the fundamental challenge for Nesfield: that he did not have the budget or flexibility to design Kinmel Hall from scratch. Instead, he was tasked with composing a house reminiscent of Hampton Court Palace by remodelling the mundane Greek Revival house existing on site. While a walk around Kinmel Hall today would not reveal the obstacles this created, drawing No. 133, ‘Revised Plan of Entrance Hall’, illustrates some of the intrinsic challenges of building for both economy and luxury, and how Nesfield chose to respond.

Perhaps the most perplexing element of this ground floor plan is the difference in colour of certain walls. The watercolour fill appears to change at random from red to grey, most notably within the walls surrounding the dining room and billiard room. However, closer analysis of the intervals of red within otherwise grey walls (signified by blue arrows) reveals that these specific spaces likely represent existing doors to be infilled by new walls during renovation. As such, it appears that red wash denotes new construction and grey wash represents existing walls that should remain. While this assumes that most of the walls on this plan were to be newly-constructed, it also reveals that Nesfield retained almost the entire block of the dining room and even incorporated the existing fenestration, specifically the windows on the garden front (located within the yellow box). Through compromise and strategic economisation, this architectural incompatibility is virtually concealed.

While using existing window spaces was workable, Nesfield’s task of designing around an existing house became more challenging when negotiating interior and exterior symmetry. Though it is difficult to see from the plan, a walk around the house’s exterior could make it appear as though the front entrance (pink box) and garden entrance (green box) are positioned on the roughly same axis at the centre of the house. In reality, the floor plan reveals that the decision to retain the existing dining room walls placed these two primary entrances on entirely different axes. Nesfield cleverly disguised this by placing each entrance under a central pavilion capped by a tall mansard roof – making both the front and garden entrances appear symmetrical and dominant on their respective sides. On the inside of the house, he embraced the challenge of retaining existing walls by creating L-shaped rooms that were functional and sympathetic to the unique plan, instead of attempting to impose spaces that would have been predictably square. Nesfield expressed this underlying challenge and imbalance on the exterior through large asymmetrical projections, such as the steeply-pitched roof of the chapel and the unequal chimney stacks, which serve as subtle indicators of the irregularity inside.

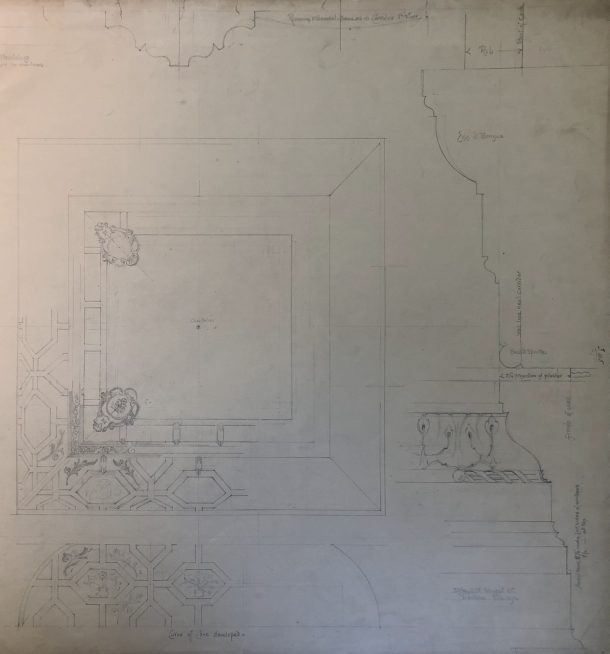

After looking at the floor plans, I catalogued the house’s variety of decorative drawings, and I began to wonder if the irregularity inherent to Kinmel is what Nesfield felt permitted him to use such an unusual ornamental scheme. While a variety of classical details allude to Hampton Court Palace and the 17th century French chateaus, after which Kinmel was modelled, a closer look reveals disparate floral (specifically sunflower) detailing that firmly places the house within the aesthetic movement. Some of the clearest examples of the ornamental variety at Kinmel can be found on its ceiling plans. While most of the ceilings contain either strictly Elizabethan strapwork or neoclassical detailing, Nesfield designed the ceilings in the house’s common spaces, such as staircases, to be stylistically hybridised. For example, the ceiling plan for the primary staircase shown above contains coved corners with Elizabethan strapwork surrounding neoclassical cartouches, and the entire composition is encrusted with small sunflowers. Together, this intentionally dramatic space combines three of Kinmel’s primary decorative influences. By utilising the ceiling of its common areas to strategically offer a glimpse of the house’s ornamental variety, Nesfield unified decorative details that might have otherwise felt incompatible.

These construction drawings reveal W. E. Nesfield’s creativity and the beauty that can result from inventive solutions to architectural incongruities. It appears that Kinmel Hall will require a similar creativity from buyers today to have a chance at survival. If you would like to view these or other drawings, please contact the Prints and Drawings Study Room to make an appointment. Details can be found here.

The following publications were referenced while writing this blog and are useful sources for further reading:

Mark Girouard, Sweetness and Light: The Queen Anne Movement, 1860 – 1900 (New Haven, 1990)

Mark Girouard, The Victorian Country House (New Haven, 1971)

Edward Hubbard, The Buildings of Wales: Clwyd (Harmondsworth, 1986)

Stephan Muthesius, The High Victorian Movement in Architecture: 1850-1870 (London, 1972)