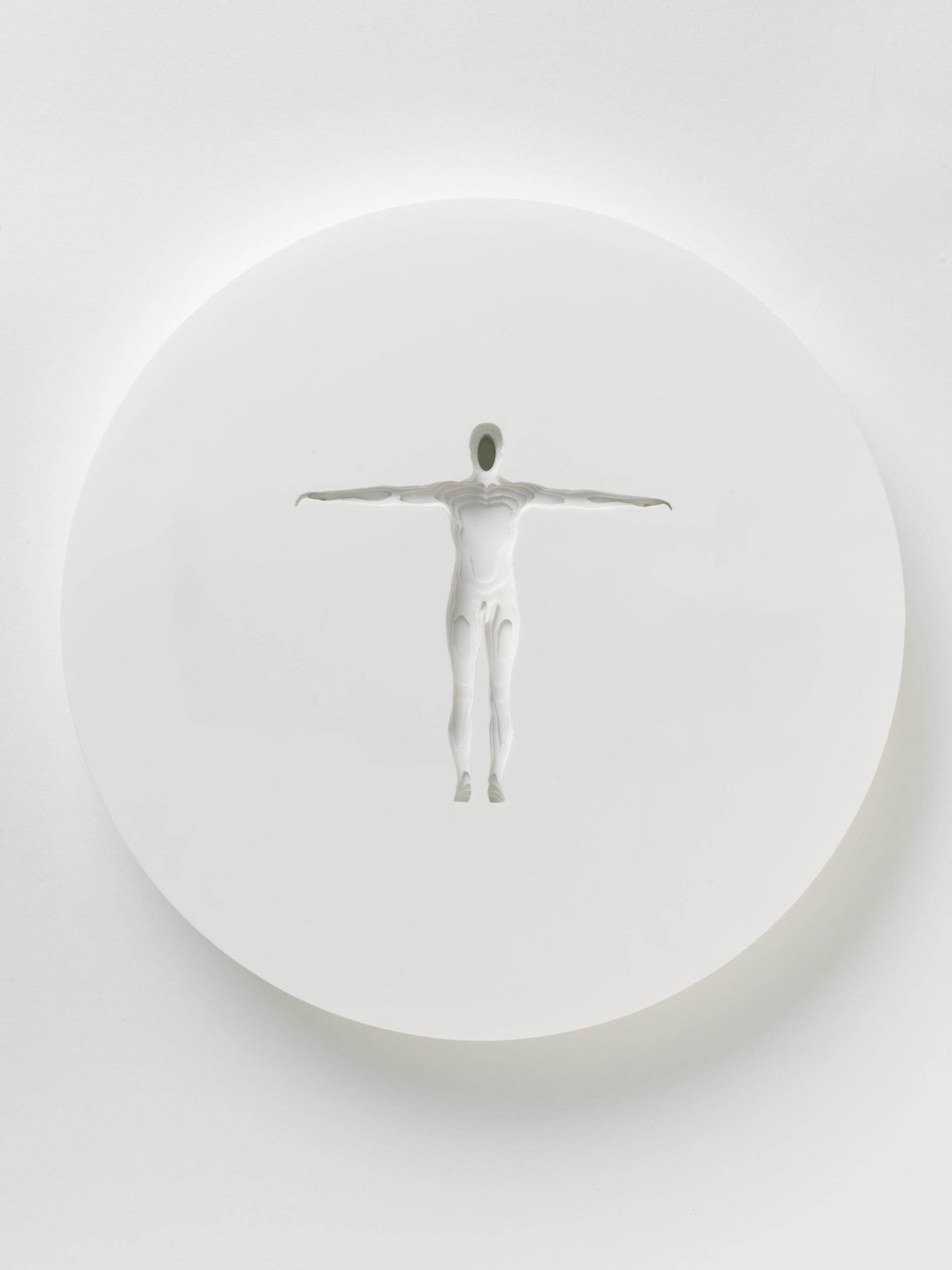

Bernard Khoury

As part of VARI’s Educational Residency I have had the pleasure of meeting and working with some glorious creatives, makers, thinkers, students and educators. This week’s blog comes from a member of that wonderful cohort. Kate O’Shaughnessy, a current Learning Associate and PhD candidate at the Institute of Education, reflects on the history and development of learning practices and talks, with care, about the importance of learning through practice.

In the late 1960s the mathematician and educator, Seymour Papert, was working on a maths project at a Junior High School in the USA, when he became interested in the art classroom down the corridor:

‘…I dropped in periodically to watch students working on soap sculptures and mused about ways in which that was not like a math class. In the math class students are generally given little problems which they solve or don’t solve pretty well on the fly. In this particular art class they were all carving soap, but whatever students carved came from wherever fancy is bred and the project was not done and dropped but continued for many weeks. It allowed time to think, to dream, to gaze, to get a new idea and try it and drop it or persist, time to talk, to see other people’s work and their reaction to yours’.

Papert notes how in the math class pupils were expected to experience the subject largely in isolation from the world they might use it in. They were expected to solve problems as if by computing the answers inside their own head. Only later, once they had mastered these principles, were they then expected to apply this knowledge within the world.

Meanwhile, across the corridor, learning was rooted in the students’ ability to engage and manipulate the world – they did first. And learnt through the discussion and talk this generated.

What Papert observes here underpins the modern notion of ‘academic’ and ‘practical’ subjects, which have come to hold considerable sway in our current education system. For me, as a philosopher, I am interested in the ways we structure our world through language, and by asking questions, such as how useful it is to categorise subjects in this way?

Asking this sort of question helps remind us that mass schooling is a relatively new invention in the history of humankind – although learning is arguably as old as us. Even before we had national education systems we had Caravaggios and Rembrandts, dazzling cathedrals and palaces, communities of midwifes and poets. Learning through apprenticeship and the work place, through doing – with its close connection between the individual learner and a clear purpose guiding learning – is the model for how most of human knowledge came to be constructed and passed on.

This is not to attack schools (which are certainly very useful) but even now, our earliest experiences of learning begin in the practical. Learning to talk in a first language is something we do many years before we come to learn its’ grammatical rules. Helping out in the kitchen, the garden, painting, looking after animals…all these activities, done in childhood, can determine life-long careers, begun long before we knew the technical names of what we were doing.

It is not helpful to imagine different types of knowledge; ‘practical’, ‘academic’ or other – or to divide learning as either taking place in the muddy grounds of experience or being delivered from ivory towers.

We all come to learning from a long heritage of common ancestry and our own personal histories, where knowledge was rooted in the use it has for us, in the world in which we find ourselves, and in our ability to make and do.

Papert took his lesson from the art class to make a new kind of maths lesson, in which students make, design, talk and (in my experience of these classes) frequently laugh. And as Papert pointed out, this is much closer to the experience of professional mathematicians, who work in communities of practice, where maths is an object of joint study, crafted and sculpted together, to allow individuals to ‘think, to dream, to gaze’.