In collaboration with colleagues across the V&A’s collections departments, our ongoing work to select objects for the new V&A East Museum galleries continues to see the curatorial team delving into the museum’s stores in South Kensington.

The collection galleries at the V&A East Museum will provide the opportunity to draw dialogues between diverse practitioners and objects across time and geography. They will create new spaces to amplify the voices of lesser known, and sometimes historically overlooked, makers in our collections.

Whilst researching our holdings of documentary photography, I have found myself discovering the inspirational work and stories of several pioneering practitioners for the first time – new to me, but of course expertly collected and researched by our colleagues in Photography.

This blog post will focus on the work of three female photographers, all working as the minority in an otherwise male-dominated field; Dorothea Lange, Grace Robertson and Newsha Tavakolian, whose careers take us from 1920s America to post-war Britain and present-day Iran

Dorothea Lange (1895 – 1965)

Born in Hoboken, New Jersey, Dorothea Lange’s first foray into photography came in the form of classes taken at Columbia University in New York. By her early twenties she found herself in San Francisco, where she took a job at a photofinishing counter at a pharmacy. It was in California that she began a career as a studio photographer, taking portraits for the local Bay Area clientele.

With the onset of the Great Depression in the 1930s, Lange sought to broaden the scope of her lens and to capture the reality of life beyond the confines of her studio. In a moment of clarity, caught in a thunderstorm, she was inspired, realising:

what I had to do was to take pictures and concentrate upon people, only people, all kinds of people, people who paid me and people who didn’t.

Arrow, J. Dorothea Lange. London: Macdonald, 1985, p.2

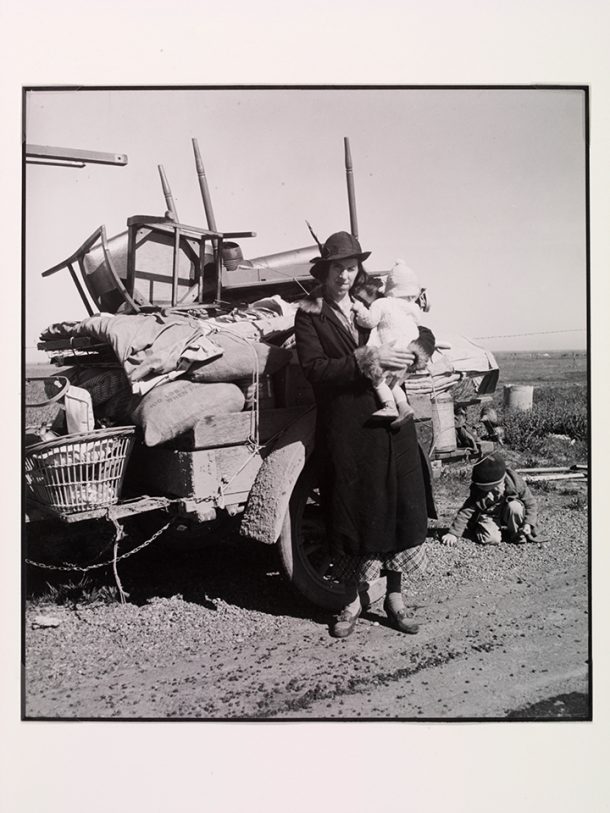

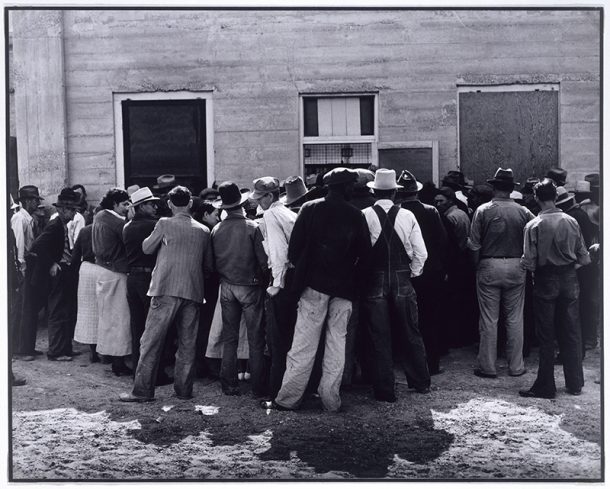

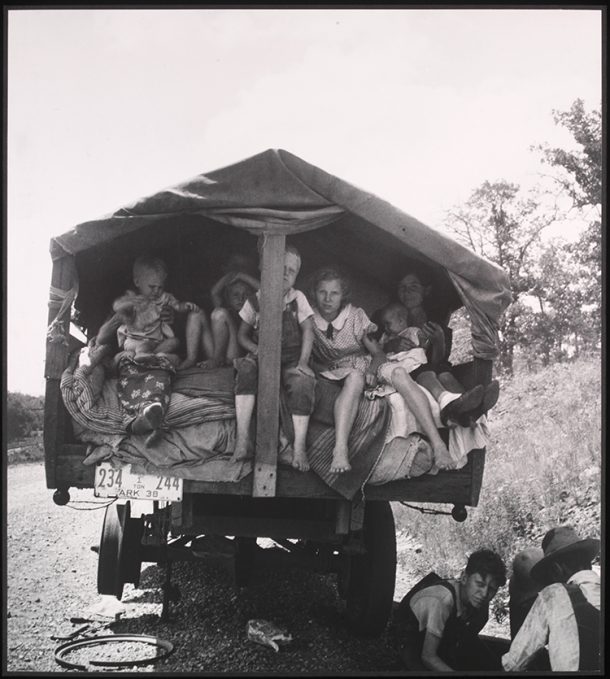

In 1935, Lange was offered a role with the California State Emergency Board (later the Farm Security Administration). She was the first woman recruited to their photodocumentary campaign, which aimed to assess the impact of the Great Depression and widespread droughts on rural California. The brief was to focus on the landscape, looking at the desertification of land but Lange found herself drawn to the plight of the people she encountered. As she travelled through California and the South of America with other members of the FSA team, she personally witnessed the effects of the Dustbowl and the Depression on the populations of itinerant workers and families.

In behind-the-scenes images of Lange working, she can be seen on top of cars, often with her iconic, though cumbersome, Graflex Super D camera. Lange’s photographs supplemented written reports, and this field work was pivotal in raising public awareness of the challenges faced by the rural population, as well as forcing a change in the administration of aid to these people, prompting urgent funding to be released to create camps and public housing. For this reason, she is often said to have ‘humanised’ the Great Depression, casting the faces of an otherwise abstract socio-economic disaster.

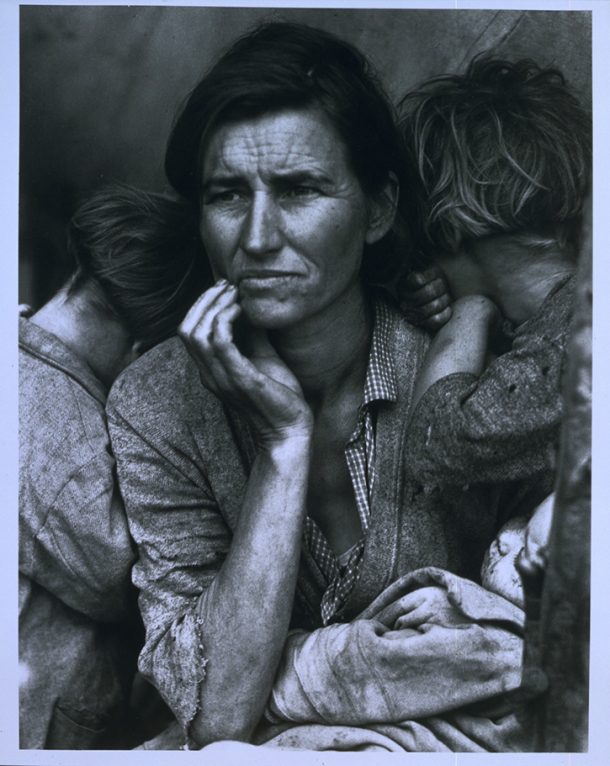

It is important to add that as Lange’s legacy has grown, so too have reflections on the questions prompted by her work, concerning the agency of subjects in documentary photography. Her most famous photograph, shown here, has come to be known as ‘Migrant Mother.’ Originally, Lange gave this the caption ‘Mother of seven, destitute migrant pea-pickers,’ but it has taken on the status of an icon. It has been decontextualised, reproduced and appropriated for numerous causes, whilst silencing the subject, Florence Owens Thompson.

Grace Robertson (1930 – 2021)

As mentioned, we have been scoping widely in the collection with the support of colleagues in collections departments. We are very grateful to Caitlin Langford for introducing us to the work of Grace Robertson. Born in Manchester, England, she left school aged 16 to care for her mother who had been diagnosed with Rheumatoid Arthritis. Shortly before her eighteenth birthday, Robertson waited in a queue at the local butcher’s shop where she noticed two women talking. It was this seemingly banal moment that sparked her imagination, as Robertson realised that she was looking at a living tableau of a documentary photograph. After rushing home, she took out copies of then-popular national magazine, Picture Post.

I spread them over the floor. Everywhere faces stared back at me: war criminals, statesmen, tribal chiefs, evangelists, and again and again, the faces of ordinary men and women. There was even a picture of a food queue, in Berlin. I crouched there for some minutes letting the message sink in: this is it, I said to myself, this is what I want to do, take pictures like these.

Grace Robertson, Grace Robertson: Photojournalist of the 50s, London: Virago, 1989, p.8

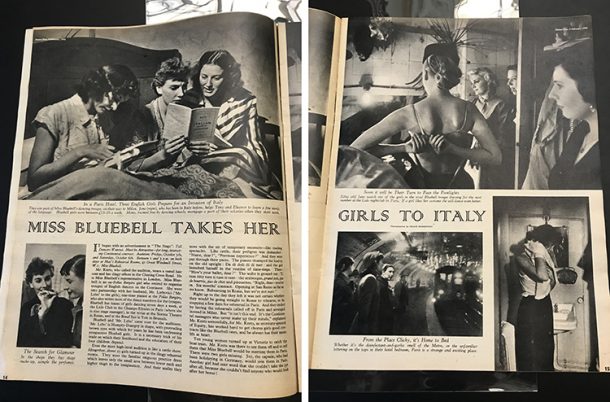

At this time, photojournalism was considered a male profession, but Robertson’s father was encouraging of her aspirations. A journalist himself, who worked for the BBC and Picture Post, he insisted that Grace should have a Leica and purchased a second hand 3B model for her. Robertson would take day trips to Brighton and London, in search of new material to photograph. At this time, it was highly unusual to use a miniature camera for press photography and Robertson was even laughed at for working with a 35mm camera. What it may have inflicted in mockery, it made up for in the relative invisibility it granted. Robertson could be discreet in her environment and capture images that were unprompted and natural.

In later years, Robertson also explained that she would use a viewfinder to create further distance between herself and her subjects. In this way, the camera granted anonymity and a tool by which Robertson could merge with her environment to capture genuine interactions and unstaged compositions.

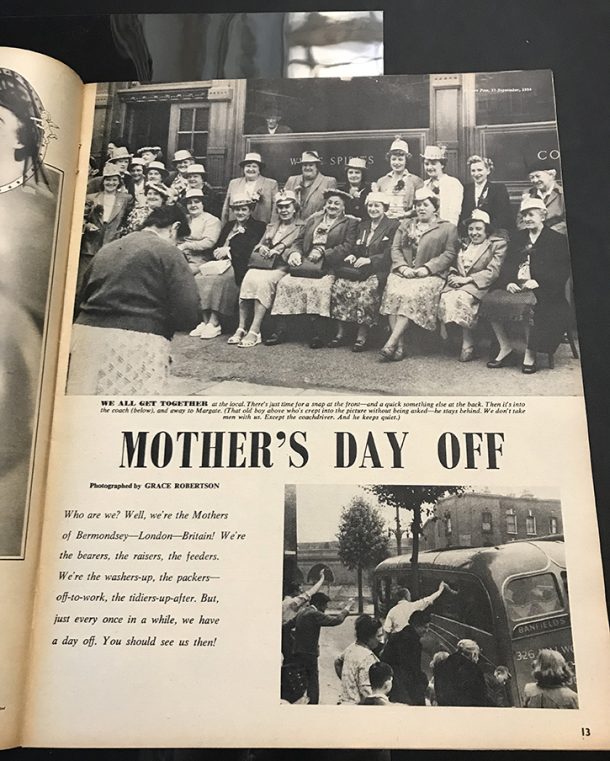

After rejections for her initial submissions to Picture Post, Robertson successfully published her first series of photographs in 1951, with the subject of her sister doing her homework. Numerous commissions followed and, in 1954, ‘Mother’s Day Off’ was published. Robertson had pitched this photo story, following a group of women travelling from Bermondsey to Margate for their annual outing, but it had initially been rejected on the grounds it lacked broad appeal. Robertson went ahead with the piece anyway, following her instinct. It proved an important opportunity to capture a rare insight into the friendships and frivolity of women at the time, and to document a vanishing post-war community. Once the editors of Picture Post saw the results, they agreed to run the piece and, a testament to Robertson’s photographic eye, the images would become iconic.

For more about Grace Robertson’s life and work, please see Caitlin Langford’s article.

Newsha Tavakolian (1981)

Like Robertson, Newsha Tavakolian left school at 16 due to her dyslexia and is a self-taught photographer. Born in Tehran, Iran, she began her career in press photography, amidst the precarity and tension of Iran in the 1990s. Tavakolian contributed photographs to several reformist Iranian newspapers and magazines, all of which have since been banned. This included the only national Iranian women’s publication, daily women’s newspaper Zan-e-Rooz (Woman of Today), and she was one of just a handful of female photographers operating in the country. Over time, she has shifted her output from journalistic to artistic pieces, finding freedom from societal expectations through the photographic lens.

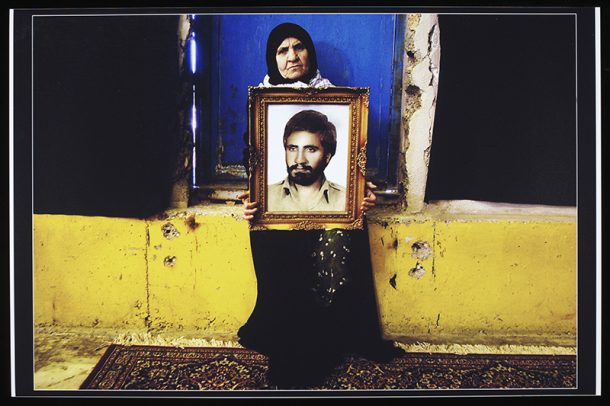

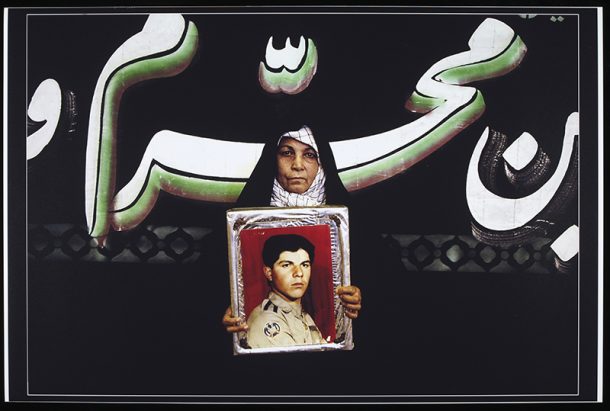

Reflecting on her identity as an Iranian woman, she has shared that the role of artist allows her to examine subjects with which she would otherwise be unable to engage for political or cultural reasons. In the series ‘Mothers of Martyrs’, one of the works of which can be seen here, Tavakolian presents double portraits, of women and their sons, who were killed during the Iran-Iraq War (1980 – 88), a brutal conflict sparked by Iraq’s invasion of the newly formed Islamic Republic of Iran.

As viewers, we are confronted by their sorrow and the harrowing realisation that as these mothers age, their sons only survive in images, remaining forever young. Of the Iranian casualties, an estimated one million men and boys died during these eight years, leaving a generation of bereaved mothers and wives. Nevertheless, there remains a deep sense of pride in this lost generation, who have become mythologised as stalwarts of Iranian independence. These arresting works testify to the capacity of photographs as a unique, poignant and vital bridge between past and present, and how our relationship with them, whether adoration, preservation, loss or destruction, performs a key role in the continual shaping of personal and national identities.

From female guerrilla fighters in Iraqi Kurdistan and Syria to Iranian female singers, banned from performing due to legislations, Tavakolian’s work shines a light on the stories of people that may otherwise be invisible to the wider world, documenting the experiences of women and those living in conflict and under sanction. It makes sense, therefore, that Tavakolian primarily thinks of herself as a storyteller. She looks to capture, critique, and celebrate Iranian culture, primarily for Iranians, but also to redress misconceptions about Iran proliferated by the Western camera lens.

Across the practice of Dorothea Lange, Grace Robertson and Newsha Tavakolian, the camera is adopted as a tool to empower others. Their work documents the experiences of those who might otherwise be unseen and unheard by society. When each has spoken of their practice, they have presented their role in terms of being a conduit to the true stories and lived experiences of others, capturing life as it really is, visually telling that story and positioning the viewer as a witness.

We look forward to the V&A East Museum galleries being a space to juxtapose and draw out synergies that connect the agendas of makers such as these three pioneering photographers, across periods, cultures and geography.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to Catlin Langford, V&A Curatorial Fellow in Photography, supported by The Bern Schwartz Family Foundation for her insights into Grace Robertson’s life and work. Please see her brilliant article here.