As I restart my residency at the V&A Museum of Childhood, I want to reflect on the past few months and my pre-lockdown research. As museums around the world closed their doors, it got me thinking more and more about the buildings themselves. What is the role of a museum building? What is a museum without a building? How can a building enhance the museum experience, and how do museums best work with their outside spaces? These questions led me down an exciting path into the history of the V&A Museum of Childhood.

The Building

My research has focused on the transition between inside and outside spaces in museums. Thinking about the opportunities of the V&A Museum of Childhood’s outdoor spaces inspired the idea of ‘The Outdoor Gallery’. However, much of the research had to begin from inside in order to fully understand the building in its entirety.

The building is really a huge flatpack pavilion that was placed on the former common after a journey that moved it from West to East London. It is a grand treasure box with a large public space at its heart, decorated with a playful mosaic floor. The enormous structure is supported by slender cast iron columns and has a soft vaulted ceiling which captures the natural light. The outdoor space is enriched by a generous front plaza facing the main road and wide lawns facing Museum Gardens, the park next door.

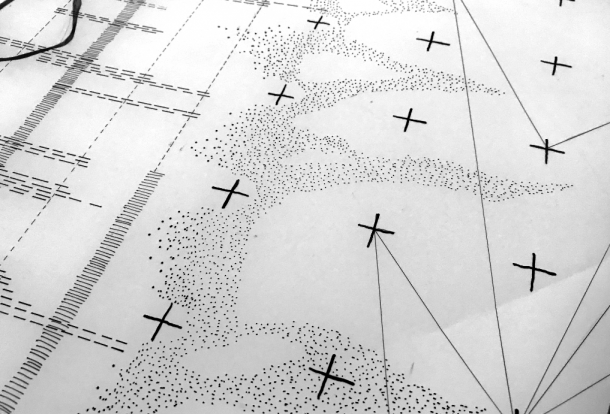

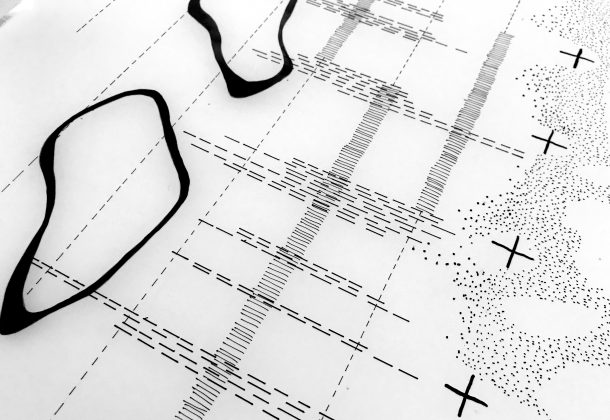

I started to record and reimagine all of these features, distorting them in my sketches and creating new imaginary structures for interaction between the public.

Between the Street and Galleries

The V&A Museum of Childhood was planned by James W. Wild in 1862 as part of a larger complex of public facilities including St. John’s church, the library and Bethnal Green Gardens. The original plans also included orchards, a paddock, a kitchen garden and pleasure grounds, allowing local residents to grow crops and graze cattle.

It was typical for a museum of that time to make a physical disconnect between the street and their galleries. Museums were built with majestic columns, steep front staircases and windows set just a little too high for people to look inside.

The Billboard

I believe outdoor spaces can provide opportunities for museums who want to reach their audiences in a safely distanced way. What if the V&A Museum of Childhood could communicate with residents and commuters strolling past on a daily basis? The windows already frame a dialogue between the outdoors/indoors and light/shade. Could they become a changing billboard that plays with the mosaics by F.W. Moody depicting educational scenes of human work and celebrating art and industry?

Could they become a point of reference in the city, like the Fourth Plinth in Trafalgar Square? It might make the outside of the building come alive, offering a story and some much needed entertainment on a daily commute.

The Forgotten Waterfall

As I continued to explore the outdoor spaces at the V&A Museum of Childhood I came across a forgotten fountain – ‘The Waterfall’.

I knew of its existence, but I had no proof that it was ever moved to Bethnal Green, until… there it was! During a visit to the V&A Archives at Blythe House, a photograph emerged showing the 12-meter-tall water fountain. In the background is the original Bethnal Green Museum.

What an act to be greeted by upon arrival. Made from 369 separate parts of Majolica, the fountain included a series of bowls from which the water would fall, making a musical, relaxing sound. Displayed at the Great Exhibition of 1851, the main basin circulated 700 gallons (the equivalent of 5,600 pints of milk) of perfumed water each hour, filling the space with fragrance.

Imagine the sensory experience of freshness, movement, and smell! In Bethnal Green the fountain created an informal space for visitors to linger and meet, sharing their experiences of the museum and impressions of the collections. I see this fountain as a valuable testimony to the original informal outreach of the museum, which made it (from the very beginning) a sensory place connecting the street to the gallery.

Back in the present, I am thinking about the past few months and how the traffic that normally occupied the streets gave way to pedestrians and children playing. Reflecting on the role of the Forgotten Waterfall from the museum’s past, I ask myself what could be done to welcome more young people to engage with the museum and its spaces? Could the spirit of the old common and the original pavilion make the museum more informally accessible?

For now, these questions may go unanswered. But as we approach an exciting period in the V&A Museum of Childhood’s history, we have the opportunity to rethink the role of the building and spaces that make a museum.

This residency is supported by the Danish Arts Foundation.

Learn more about Anne Marie’s work and workshops on her website.

Follow her on Instagram.