The Rodin gift as it was seen at the time

On 8 November 1914, the great French sculptor Auguste Rodin gave the V&A eighteen of his sculptures in honour of the French and British soldiers fighting in the First World War. In the weeks running up to the 100th anniversary of this event, we are charting the story behind this remarkable gift.

The Rodin gift to the V&A was immediately seen as a monument: in the Daily Telegraph ‘not only to the British heroes who had fallen, but to those who live, and carry high the banner of freedom, side by side with their most valiant brethren of France’. The Times (11th November) claimed that the gift would be remembered as a monument of ‘this momentous crisis in the history of Europe’ and concluded, ‘There are very few artists in the whole history of art who could make a gift worthy of such an occasion, but M. Rodin is one of them – one with Michelangelo and Donatello, and with the earlier masters of Greece’. Rodin himself was quoted very simply (Daily Telegraph, 12th November):

‘The English and French are brothers; your soldiers are fighting side by side with ours. As a little token of my admiration for your heroes, I decided to present the collection to England. That is all’.

The Ladies Field (21st November) was one of many newspapers to express the gift in more political terms: ‘we need look no further for a lasting memorial of the Entente Cordiale’. Rodin was credited by the President of the Board with a significant international role: ‘C’est un nouveau lien entre les deux nations que votre generosité a forgé’. His gift was immediately seen as strengthening the connections between the allies, which were crucial to the outcome of the momentous events which were unfolding at the time.

One of Rodin’s most enthusiastic admirers, Claude Phillips, described the gift as ‘a monument of unsurpassable beauty and grandeur dedicated by one of the most famous of France’s children, not only to the British heroes who had fallen but to those who live, and carry high the banner of freedom and civilisation, side by side with their most valiant brethren of France’ (Daily Telegraph, 12th November). The British public had seen dramatic headlines and double-page spreads of images in newspapers conveying the intensity of destruction in these first months of war, particularly at Louvain and later of ‘Ypres in flames’, as well as in France itself. The Daily News specifically portrayed Rodin’s work in the context of heritage which was under attack: ‘its significance at such a moment is paramount, for the masterpieces stand as the highest expression of the very thing our men are fighting for – the preservation of the culture of the race’.

At the V&A, the presentation of the gift to the public was itself the subject of dispute. The Secretary of the Board suggested English for temporary signage but Latin for permanent inscriptions on the walls. Smith retorted that a Latin inscription and decorative border would be …‘quite out of harmony with the practice and purposes of this museum. Ninety percent of the people visiting this place would be quite incapable of reading Latin’. He added curtly, ‘of course we should welcome any suggestions for improvement that might reflect the attainments of the scholars and writers at the office in Whitehall’. This provoked further irritation. It was eventually agreed that Rodin’s gift would be presented with a simple public notice, explaining the motivation behind it. The final draft text for the notice was written personally by the Secretary of the Board of Education and sent to the V&A. Handwritten in bold red ink it read:

AUGUSTE RODIN

GAVE THESE SCULPTURES

TO THE VICTORIA AND ALBERT MUSEUM

IN HONOUR OF THE BRITISH

SOLDIERS FIGHTING BESIDE

HIS COUNTRYMEN IN FRANCE

NOVEMBER 1914

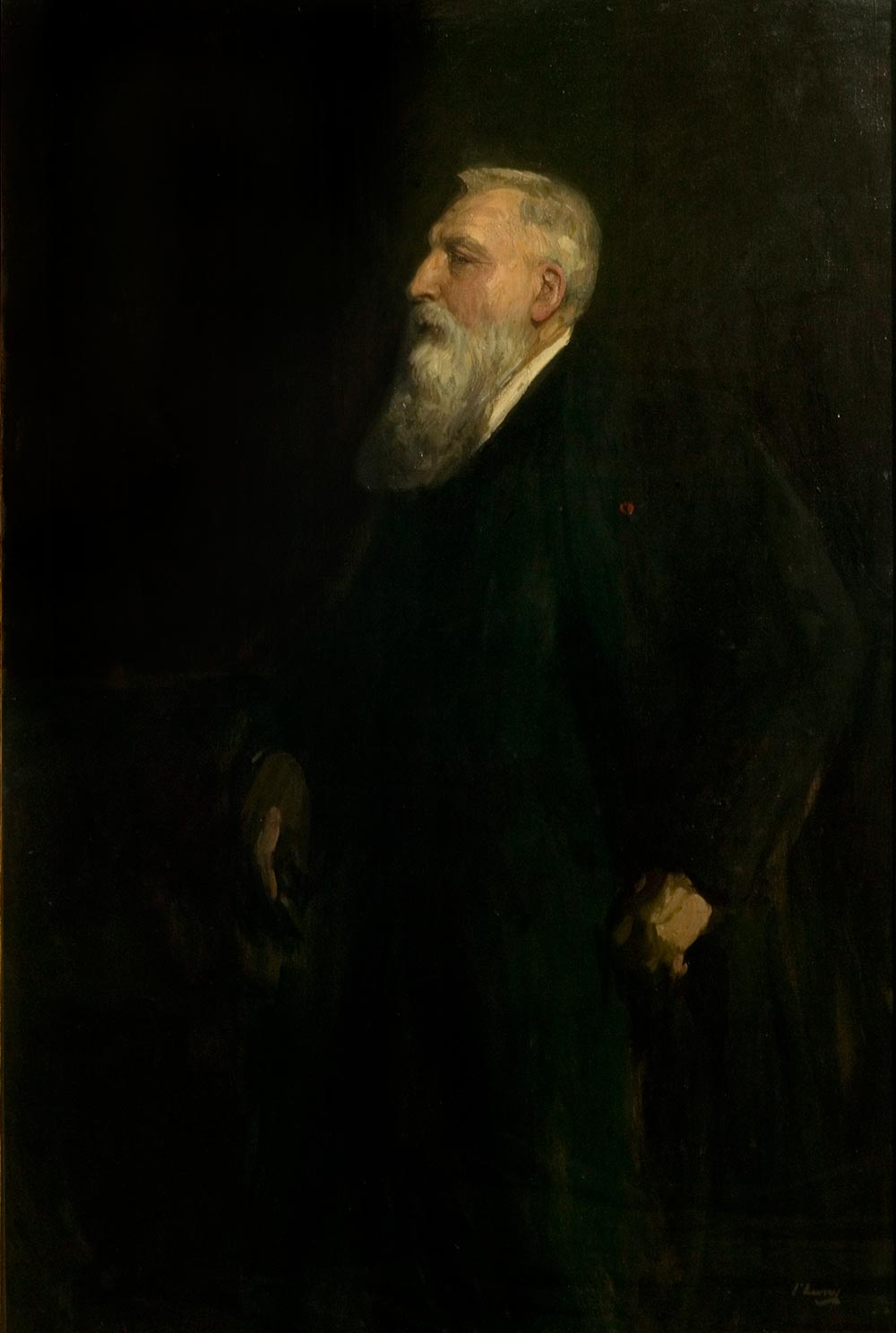

Alongside the sculptures in the West Hall, a portrait of Rodin painted the previous year by Sir John Lavery was displayed. He presented it to the V&A in November 1914 as ‘a tribute from British Art’ and ‘to reciprocate the sentiments which inspired Rodin to make his magnificent gift of sculpture’ (Morning Post 26th November). Lavery was a highly-regarded artist whose portrait of the Royal family had been exhibited in 1913 at the Royal Academy and was displayed there again in January 1915 to boost morale, where it attracted a considerable number of visitors at the time of the Academy’s War Relief Exhibition.

To Rodin’s annoyance, his sculptures were lent to the Royal Scottish Academy, Edinburgh, in August 1915. In their place, an exhibition of works by Ivan Meštrović was held at the V&A, organised by the Serbian Government and agreed to within the political context at the time. Maclagan assured Rodin that his works would be redisplayed exactly as they had been arranged when they returned in September. The following year, Rodin’s major gift to France was finalised. This gift by Rodin, then aged 76, was also seen by the British Press (Manchester Guardian) within the wartime context as a boost to propaganda, as it ‘proclaims to the world with a superb gesture his triumphant faith in the spirit of France, now, as the world believes, approaching the end of her travail’.