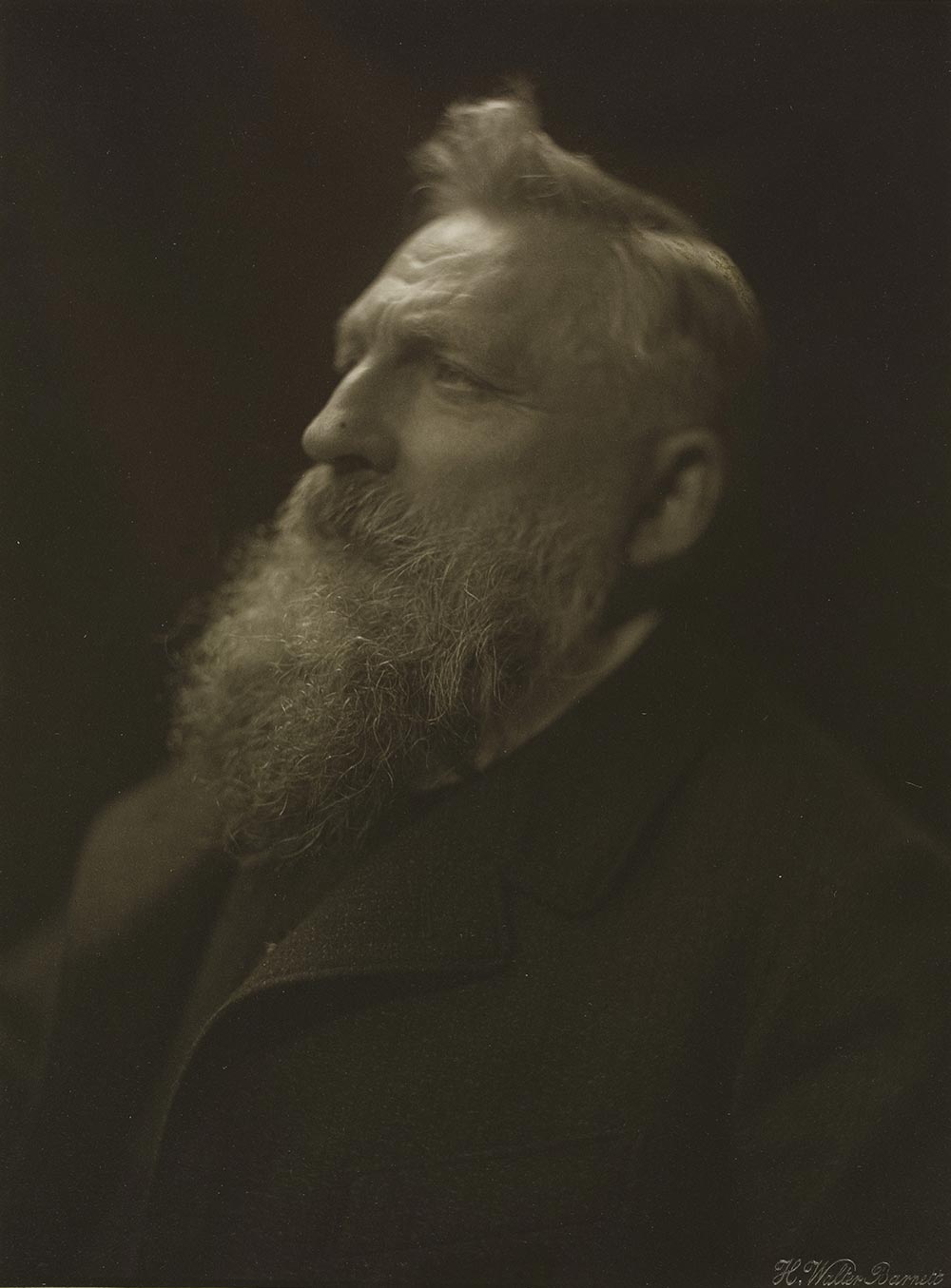

Rodin and the V&A, 1902 – 14th September 1914

On 8 November 1914, the great French sculptor Auguste Rodin gave the V&A eighteen of his sculptures in honour of the French and British soldiers fighting in the First World War. In the weeks running up to the 100th anniversary of this event, we are charting the story behind this remarkable gift.

Rodin’s magnificent donation of eighteen sculptures to the V&A at the outbreak of the First World War remains the greatest gift to the Museum by a living artist. It was presented against the background of dramatic events as these were unfolding, and it followed considerable debate about Rodin’s work and its place in the V&A. The Rodin collection has now been seen and admired by millions of visitors to the V&A over a hundred years, but the path which led to its acquisition was not a smooth one.

From at least 1880 Rodin built up a group of admirers in England while his career was taking off relatively slowly in France. The group included W E Henley, Editor of the Magazine of Art, and the sculptor Alphonse Legros, who both promoted his work in London. Rodin himself was warmly welcomed during visits to London in the early 1880s, but although he exhibited regularly at the Royal Academy, the art establishment was not united in its praise for his work. Partly for this reason, Rodin did not return to London until 1902. This was a turning point. His St John the Baptist was presented to the V&A after a public subscription and in May, at a celebratory dinner in his honour at the Café Royal, Rodin was given a particularly rapturous reception.

Ten years later, the Rodin galleries opened at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, with works given by the sculptor. His international reputation was by now well established. In London it was reported that Rodin felt honoured that a cast of his Burghers of Calais had been acquired by the National Art Collections Fund for the British Nation (Morning Post 28th May 1912). The subject depicted was immediately understood in the context of the historic relationship between England and France, but there were months of disagreement about the proposed location and height for display. Due to the war, the official unveiling of The Burghers was ‘indefinitely postponed’ (The Times 6th January 1915) and only finally achieved in July 1915.

In July 1914 a major exhibition took place in Grosvenor House, London, of modern French Art. Rodin was the only sculptor to be represented, exhibiting alongside artists including Cézanne, Gauguin, Monet, Degas, Renoir and van Gogh. The works included his marble ‘Cupid and Psyche’, terracotta ‘Head of Dante’, and sixteen bronzes. Amongst the latter were several much-admired portraits, the ‘Age of Bronze’, a patriotically re-named ‘La France’, and a group of avant-garde, fragmentary sculptures which exemplified his later, more conceptual work.

The exhibition ended on 21st July and, when war was declared a fortnight later, the works were stranded in London. Several options were considered in terms of what to do next. At Rodin’s request, his friend, the British sculptor John Tweed agreed to house the works in his studio. Here they were seen by Eric Maclagan, who was in charge of Architecture and Sculpture at the V&A. Maclagan became a key advocate of Rodin’s work and negotiator between Rodin and the Director of the Museum, Sir Cecil Smith (later, Harcourt Smith).

In terms of considering taking the group on as a loan, Maclagan wrote to Smith on 3rd September, ‘I know that you do not much admire Rodin’s work; but I do feel that this is an opportunity that ought not to be missed’. He also argued that the St John was not a favourable example of Rodin’s work and mentioned that Rodin might give the Age of Bronze to the V&A; a very desirable potential outcome. He added, ‘we should, I think, be doing a public service to England and France in taking charge of the bronzes until they can go back to Paris’. His sense of patriotism and politics seems to have swung the balance. Smith replied, ‘I suppose in normal circumstances a loan exhibition of modern French sculpture would be rather outside our function, would it not?’ but he also felt that the situation was ‘quite exceptional’. He suggested display in the spacious North Court (which had become available following the cancellation of an exhibition of Arts and Crafts, because of the war) writing positively, ‘I am not afraid of giving a good thing lots of room’. He added a final caveat about insurance: ‘supposing a bomb were dropped on the museum, we take no responsibility’.

On 14th September 1914 Rodin visited the V&A for lunch, accompanied by his friend and unofficial representative, John Tweed. The meeting was a success. Maclagan reported that Rodin had liked the Michelangelo wax, the ‘Leontes’ figure as well as the beer in the grill-room, and that he had mentioned the possibility of the gift of ‘one or more pieces of sculpture later on’. The loan for six months of the whole group was formally agreed and the works collected from Tweed. Maclagan then turned his thoughts to displaying the group. This included the suggestion that as the war was directly responsible for the loan of sculpture it might be appropriate to invite contributions to the French Red Cross or a similar cause with a donation box placed near to the display, at a time when other temporary exhibitions in London were raising funds for the war effort.