Sadly lost amidst our endless Brexit debate was the recent publication of Arts Council England’s ‘Durham Commission on Creativity and Education.’ The work of an impressive cohort of educationalists, academics, teachers, and artists, the Commission was conceived by ACE Chair Sir Nicholas Serota to push the government into confronting the ongoing challenge in creative education.

To my mind, it is a substantive and interesting piece of work that does not shy away from the current crisis – and, most notably for us, supports the strategic direction which the V&A is pursuing when it comes to encouraging the take up of design and technology in English schools and the transformation programme for the Museum of Childhood.

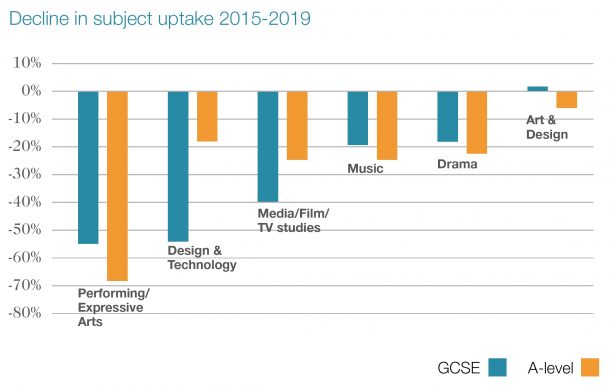

The Commission’s starting point is that there should be no pedagogical divide between knowledge and creativity. What is more, creativity should suffuse all elements of the curriculum – from mathematics to foreign languages. But thankfully, it does not allow this truism to dull its focus on championing the role of arts education in English schools. As a result, its starting point is clear: ‘The Commission believes that the arts make an invaluable contribution to the development of creativity in young people. We are therefore deeply concerned about the reduction of status of arts subjects including art and design, dance, drama and music within schools.’ And for all the talk of STEM and ‘enabling subjects,’ it rightly stresses how tough and rigorous a creative arts education is: ‘creative thinking may appear spontaneous but it can be underpinned by perseverance, experimentation, critical thinking and collaboration.’ These being exactly the skills sets which modern employers are most attracted to.

To counter the decline, there are some positive and detailed policy suggestions. The Commission highlights the negative impact of the introduction of EBACC accountability criteria on creative teaching within schools; supports the new OFSTED framework for judging schools on a ‘broad and balanced’ curriculum; urges a review of the Artsmark award for art and creativity in schools; and thinks the Government should reconsider boycotting the international PISA evaluation of creative thinking in 2021. It also highlights the 8% fall in school spending per pupil between 2009/10 – 2019/20.

For the V&A and our education ambitions, there are two particular areas of note. The first is the sustained focus on the current social inequality in creative provision. In the Foreword, Nicholas Serota stresses how, ‘it is among young people from disadvantaged backgrounds where opportunities for creativity are now most limited.’ The Commission continues, ‘When students’ experience of subjects such as art and design, dance, drama and music is limited or indeed non-existent, they become the province of the privileged … Young people from disadvantaged backgrounds and students attending state schools deserve rich and varied experiences of excellent arts and cultural education.’ That essential truth – more poetically conceived by William Morris (who didn’t want art for a few, anymore than he wanted education for a few or freedom for a few) – is the reason why the V&A Design Lab Nation has deliberately focused its efforts on lower income communities in often post-industrial settings, partnering with schools in Sheffield, Stoke-on-Trent, Coventry, Sunderland and Blackburn – and, in the next round, Doncaster and Ipswich. The Durham Commission has again highlighted the urgent need for the work we do.

Secondly, the Commission has clearly realised the fundamental importance of Early Years provision with a welcome call for a step-change in the training and quality of teachers and carers. Historically, this is an area in which Britain has systematically fallen short: public debate is usually much more focused on subsidising higher education than supporting excellent nurseries. Crucially, the Commission highlights just how significant a diet of high-quality creative stimulation is for the emergent brain. ‘In the first few years following birth, new neural connections are formed in a child’s brain at the rate of over a million per second,’ notes the Commission. ‘Exposure to a creative learning environment helps children to develop physically, socially, emotionally and cognitively.‘ What that requires is something like, ‘Creative play, movement, music, mark-making, storytelling and make-believe’ – these form the crucial foundations for subject learning in later education. In short, exactly the kind of provision we are seeking to create at the new Museum of Childhood: a space less about the material culture and social history of childhood and much more focused on providing exactly the sort of creative stimulation that, the Durham Commission suggests, spark young children’s curiosity, creativity and imagination, and support the development of communication skills.

There is much else in the report of note for us – not least in terms of inequality around extra-curricular provision – but it is heartening to see some of our key strategic goals underpinned by the latest research. In the coming months, we will seek to be working more closely with the Durham Commission to learn from their evidence-taking and highlight our own response.

nice!