Travel is still restricted, borders are strictly monitored. At this moment, I daydream about flying to the most faraway countries. When we can’t move at all, I travel in my mind, and think of the many different ways of representing space, and time, on a flat surface.

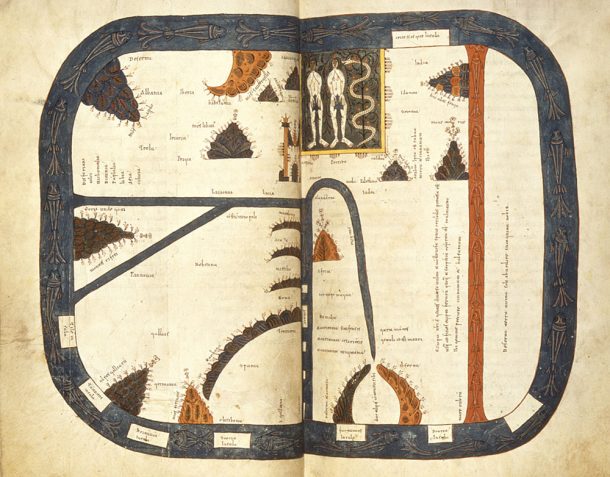

We often think about maps as representations of space, but some maps show time. Medieval maps of the globe,1 for example, not only represented the continents and waters known at the time, but according to the contemporary Christian vision of history, showed what happened before the beginning of time, and what will happen at the end of it: the Garden of Eden, and the Final Judgement.

Many Medieval representations of space are often not maps at all. Like road directions, they would guide you through a series of descriptive instructions, often using time to quantify the distance between different stages of a journey, with drawings of spatial landmarks such as a particular tree, or a well, or the city walls.

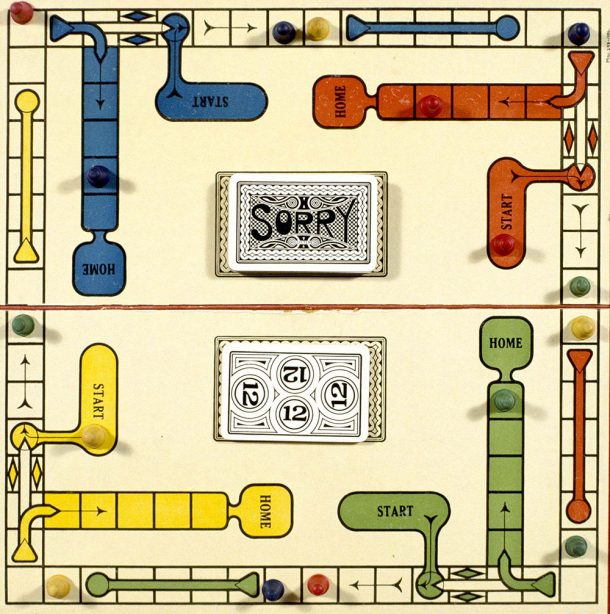

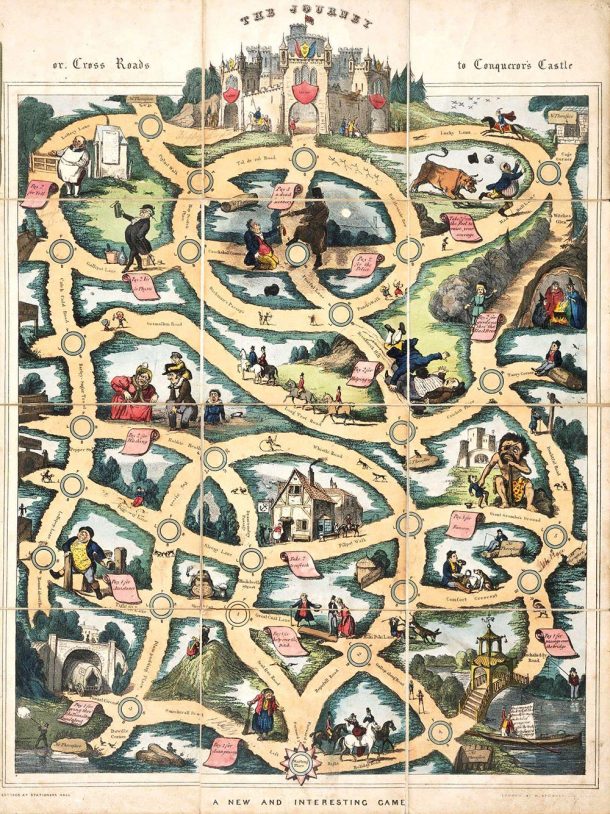

Through my work with the collection at the V&A Museum of Childhood I have come to realise how many board games show a narrative of events that evolves within a spatial frame, laid out on a flat surface. Using a game piece, some dice or a set of cards, our mind proceeds through a geography of lines, squares and circles through which we may move on, slip back, jump forward, skip a round. Portraying an almost lifelike series of events, we may succeed or fail, ‘live’ or ‘die’. Games are also played and re-played: each ‘round’ of the game offers an opportunity for a new course of events.

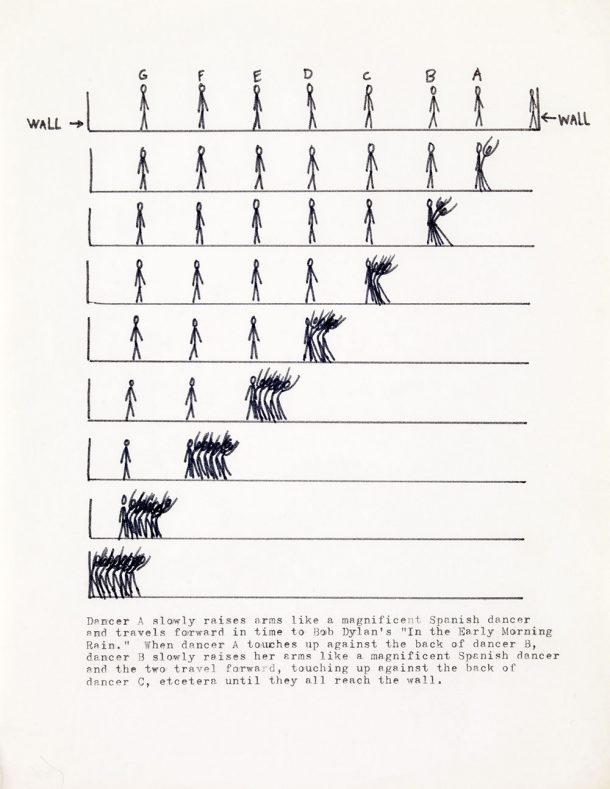

Dance choreographies are also often dreamt up as a series of events happening in space and at a particular time. Unlike music, dance does not have a unified notation system. There are no pentagrams or keys to exactly tell others how to reproduce what you just composed.2 For this reason, dance scores are incredibly diverse and often use descriptive instructions and drawings rather than, or as well as, a spatial- or time-frame. In a similar way to some Medieval maps, they sometimes describe what to do at each stage of a trajectory: when you get to a particular point in music, for example, or when you encounter another dancer on stage.

In our everyday lives, the city is inscribed with signs and marks that choreograph our movement. These ‘scores’ cause us to hop on one side, turn around, go backwards, go forward. Since the start of the pandemic, we have all become more aware of these, and they have acquired a new significance: playing the rules of the game of street choreography may make the difference between sickness and health, life and death.

We will be able to move again soon – hop on a plane, be close to our friends and family, dance with others. Perhaps board games, maps and dance scores will not resonate in my mind in the same way then. And perhaps we will all pay less attention to marks and signs around the city. But something beyond time and space will become visible again – the invisible connections between our bodies and minds: our social interaction. Like in a chessboard with only one colour pieces, the negotiations on our movement will be based only on trust, and the ability to look after each other.

1 – World maps (mappae mundi in Latin), common in Western Europe between the twelfth and the fourteenth centuries ‘show not only the world’s geography, but also the whole of human history from a Christian standpoint.’ A. Scafi, Maps of Paradise (British Library 2013), p.55. ↩

2 – Most formalised dance notation systems that have emerged, such as Labanotation, notoriously failed to reach widespread use (for example, M. Van Imschoot, ‘Rests in Pieces: On scores, Notation and the trace in Dance’ in M. Copeland, Choreographing Exhibitions, 2014). This has partly been because – differently from music – it is physically difficult to read a score and dance at the same time; it is much easier to learn movement by copying someone else as they dance. Therefore, most choreographers use annotations to elaborate and clarify their movement design as part of their creative process, and only occasionally use scores to communicate the idea to the dancers. ↩

absolutely brilliant