Production models are the vital link between an idea on paper, and manufacturing in the factory. They translate two-dimensional designs into three-dimensional prototypes made of clay, from which moulds for manufacturing are created. Many of Wedgwood’s current shapes are based on models from over 250 years ago.

Inspired by our project to catalogue our stored collections (see more on Explore the Collections) we recently took the opportunity to display these amazing objects, which you will not be able to find in many other Wedgwood collections.

Here at the V&A Wedgwood Collection we are incredibly lucky that we have always had a very close relationship with the Wedgwood factory. Not only are we located on the same site as the very factory that still produces Wedgwood’s most intricate products, but our collection has also grown from the factory’s earliest records from the time of Josiah Wedgwood (1730–1795) and his famous ‘Etruria’ factory in Stoke-on-Trent.

So it comes as no surprise that while many objects may have started their lives as factory ephemera, they have, over time and through their inherent significance, become objects of art in their own rights.

But what exactly are these models? How where they made and what were they used for? To find out, and understand the processes involved, we drew on the expertise of our master modellers on site who have worked here for many decades.

A ceramic object can be made in many different ways. While we are probably all familiar with making clay coil pots in kindergarten, only some of us will know how to throw a pot on the wheel and – unless you are a ceramic artist – even fewer of us will have ever cast liquid clay with a plaster of Paris mould, or used a press mould. All of these processes will leave you with a basic form, something that can be further manipulated and decorated with clay ornaments before firing. A good example is Wedgwood’s iconic blue and white jasper where the white ornaments are applied to the blue body while still wet, and before the whole object is fired for the first time. The sweetmeat basket model shows all of the applied ornaments on the basic form of the basket, which would have been painstakingly pierced by hand.

The shape above, which takes inspiration from the classic Greek shape of an oinochoe, was produced in many different ceramic bodies and with various decorations, be it in pure black basalt, in Wedgwood’s iconic blue and white jasper, or as a heavily gilded 19th-century version. The shape number is written on the surface in ink, while the final dimensions are incised in the body. The brown patina and the residues in the crevices could indicate a cast being taken from it to make moulds to create individual parts of it, such as the head at the base of the handle. The swan surrounding the head possibly identifies it as the head of Venus, the goddess of Love. In the 18th and 19th centuries, the main body of the piece would have been thrown on the wheel.

To create such a model the modeller skilfully increases the final dimensions to allow for the shrinking of clay in the kiln, while accurately representing the vision of the designer. In the following processes, our factory models are being created from fine-grained clay, fired in the kiln. They then serve as a factory ‘standard’ for dimensions as well as decoration. As they can also be used in the process of creating a mould for production it can sometimes be difficult to tell exactly where in the process the object in question was used or indeed its age.

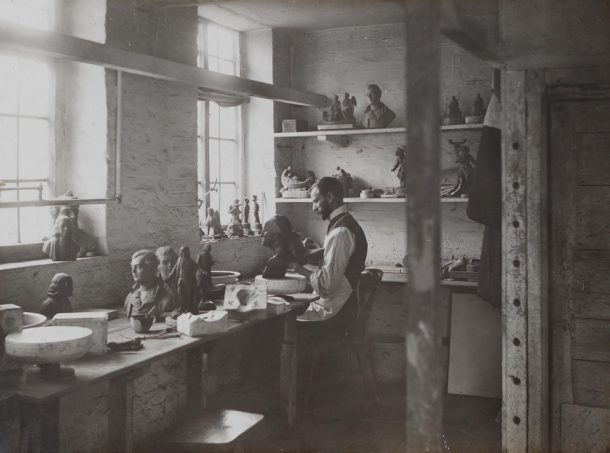

In the background of this photograph, you can see some of the factory models, such as the sphinx on the windowsill, that are on show in our current display.

Many of the models still show their unique shape numbers, used for easy reference in Wedgwood’s showrooms, catalogues, and production records and essential to avoid confusion between Wedgwood’s uncountable variations. Josiah Wedgwood refers to the practice of keeping a shape book in the showroom to let his customers browse in a letter to his business partner Thomas Bentley in February 1769 (Wedgwood archives, E25-18232):

I hope Mr. Bakewell has made drawings of the Vases wth Numb.rs to sell them by, & he must do the same to be sent here [Etruria] for the same purpose, or it will be impossible to avoid confusion.

They may be done in the same sort of a book, all the N.os we have hitherto made, & the book sent up as soon as may be, the new ones may be sent on half sheets, along with the Vases to be posted in the book here, these may be done pretty accurate, as they will be looked over by our customers here, & they will often get us ord.rs, & be a pretty amusem.t for the Ladies when they are waiting, w.ch is often the case as there are sometimes four or five diff.t companys, & I need to tell you, that it will be of interest to amuse, & divert, & please, and astonish, nay & even ravish the Ladies.

Josiah Wedgwood to business partner Thomas Bentley, February 1769

This is part of the model for the so-called ‘Michelangelo Vase’. The three supporting figures are copied from candelabras in the Treasury of St Peter’s of the Vatican, which are cast from models by Michelangelo Buonarotti. The underside of the factory model indicates two different versions – one with further ornaments applied as in the shape book on the left and the other a much plainer version, as shown in the price book on the right.

While many of the models show a patina and marks from the production process, others are bright white, as it was common to re-fire them to burn off dirt, such as this model for a so-called croquant dish a rare 18th-century shape of which only very few examples survive. The finished product was used for the display of sweetmeats.

Often factory models like this are said to be moulds, implying that an object could simply be cast. In reality, to achieve a product as intricate as this croquant dish, many hours of sprigging – applying clay ornaments to the clay shape – are necessary.

With their craftsmanship and precise detail, these factory models are not only works of art in their own right, but they also offer a unique insight into the manufacturing process.

‘IKKIS’ translates from Hindi to mean ‘21’, a number significant and symbolic in matters both physical and spiritual. It’s no coincidence that sequence, modularity, and symmetry informs how we design for 21st-century contemporary living.