We are now enjoying some of the changes brought about by the dawning of spring. Warmer temperatures and longer days finally seem to be on the agenda (fingers crossed moving forward!), as well as the prospect of flowers and plants literally “springing” into life in the gardens and parks all around us.

But how do we decide when spring has sprung? You may know of the two conflicting systems: the meteorological seasons and the astronomical seasons. The meteorological seasons are roughly decided by the annual temperature cycle and state of the atmosphere, making things easier through coordinating with the calendar months, thereby splitting the year into four 3 month seasons. Spring therefore runs between March and May according to the meteorological system. The astronomical seasons are dictated by the Earth’s orbit in relation to the sun, taking into account the equinoxes (when the length of day and night are equal) and solstices (the longest and shortest days of the year). By the astronomical system spring began on March 20 and runs through to June 21.

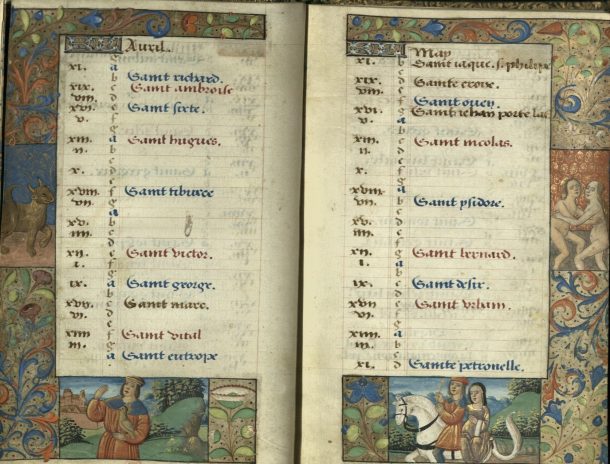

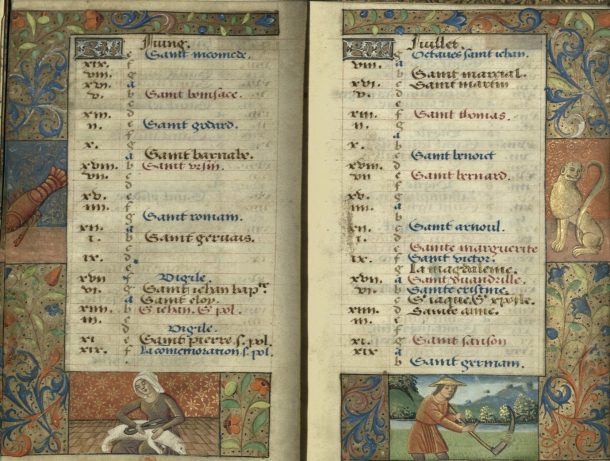

Journeying back to early 16th century France we can see how embedded in daily thought patterns these changes in the seasons were within the agrarian society of the early Renaissance period. Take a look at the calendar of the months, listing church feasts, within this book of hours use of Rouen (about 1500-1510). Here, at the front of the book, as in most other books of this type, secular pictures of men and women conducting seasonal land work predominate in what is otherwise, by its very nature, a book of Christian devotion.

If we venture now forward into Victorian Britain of the 1840s and consider the growing practice of producing compendiums, striving to educate whilst entertaining the young: ‘The boy’s spring book…’ features information on birds, their songs and nests; wild flowers; snakes; angling; types of trees and country games, including a lesson on the necessity of courage (learnt through the jumping of a fence in one such game).

The author provides the following reasoning for his creation of this cycle of books synced with the seasons, for young boys :

Most respected sirs. Like a garrulous old gossip, I am about to tell you how I came to write this work… First, then I felt fearful having written so many books descriptive of the country and country life, that I should find it difficult to produce anything new and interesting. “But,” argued a grave and learned friend, who has ever the welfare of youth at heart, “you have not yet written anything for Boys; and as you were once a country-boy yourself, you must have seen and heard many things which would be alike interesting, amusing, and instructive to them, were you to tell all you know in a light, agreeable manner, not in that silly, childish style, which is called the simple school of writing, but if aught, [be] rather above than beneath their capacities…

(Forward)

Of course, spring has long been associated with new life, renewal and an innocent state of existence. William Blake’s poem ‘Spring’ features in his ‘Songs of Innocence’ (1789), a collection of 19 poems exploring human passions and the natural early state of the soul. His later ‘Songs of Innocence and Experience Shewing the Two Contrary States of the Human Soul’ (1794) goes on to investigate the early life contrasted with the effect of social and political conventions of the adult world on the soul.

These printed gems show how spring has long been appreciated and recorded as part of the rich tapestry of the annual cycle of the seasons. We can also see through Blake’s poem how spring can stand alone as an uplifting catalyst for celebration and joy on its “own merit”.

All the items featured above can be requested to view at the National Art Library once you have registered as a reader with us. Come and visit us today on the third floor of the V&A.

Pretty! This was a really wonderful post. Thank you for providing these details.