Assistant Curator, Alex Clayton, explores some of the strangest and most extraordinary animal entertainments on offer to Londoners in 18th and 19th centuries, using material from the V&A’s Theatre and Performance Collections.

According to Ned Ward’s London Spy (1698), Londoners could find ‘Lions, Tygers [and] Elephants in every Street in Town’. Although an exaggeration, Ward’s statement illustrates the presence and significance of animal entertainments in London. These often cruel performances redefined attitudes towards the natural world, exploring national identities and pushing the boundaries of contemporary sensibility. From waltzing geese to talking fish, performances sought to push the boundaries of scientific understanding and the human imagination.

In this blog, we explore some of the strangest and most extraordinary animal entertainments on offer to Londoners in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

Operatic Cats and Theatrical Dogs

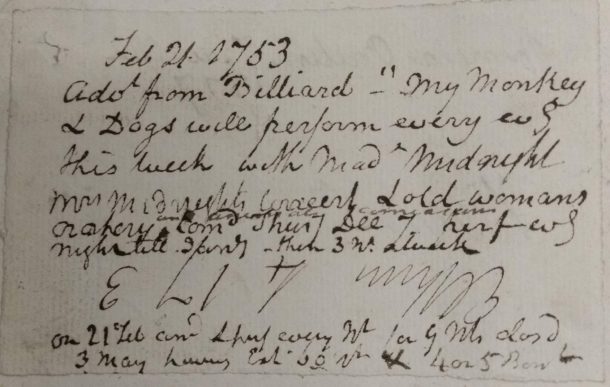

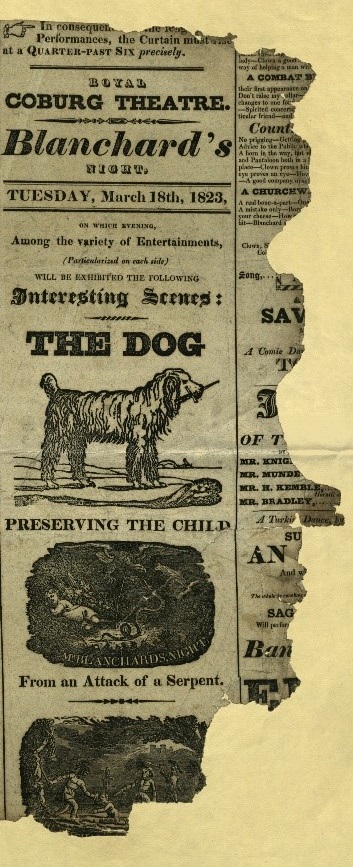

Dogs were popular choices as animal performers, since they were more easily trained and cheap to maintain. Dog acts ranged from dancing to reading minds, however they were particularly popular in melodramas. One such performance at the New Theatre, Haymarket in 1753 included monkeys defending town walls with guns, whilst dogs climbed ladders bearing swords. The battle ended with the smoke clearing, and the monkeys and dogs joined together ‘singing’ God Save the King.

Musical acts were also popular in the coffee houses and parlours of the middle and upper classes, and ranged from singing mice to percussionist hares. One of the most successful musical acts was Bisset’s ‘Cat Opera’, starring three cats striking dulcimers and squealing in different keys, all the while staring intently at the music sheets in front of them. The feline performers earned Mr. Bisset a reported £1,000 in just two months of performances.

Dancing Bears and Pig-Faced Women

Bear performances were a particularly common sight on the streets of London, so much so that owners and bears alike were often summoned to court for causing a public nuisance and traffic congestion. Dancing and tumbling were among the most common acts, and owners often competed to produce the most elaborate and novel performances.

One such show was displayed in Hyde Park in 1835, with the subject being described as an aristocratic woman born with a pig’s face. In fact, the performer was revealed as:

nothing but a bear, its face and neck carefully shaved, while the back and top of its head were covered by a wig, ringlets, and artificial flowers all in the latest fashion. The animal was then securely tied in an upright position into a large armchair, the cords being concealed by the shawl, gown, and other parts of a lady’s fashionable dress. (Wilson and Caulfield, The Book of Wonderful Characters, 1869)

This didn’t prevent the ‘woman’ from causing a sensation in London, receiving gifts, love letters, and offers of marriage.

S.1133-2010

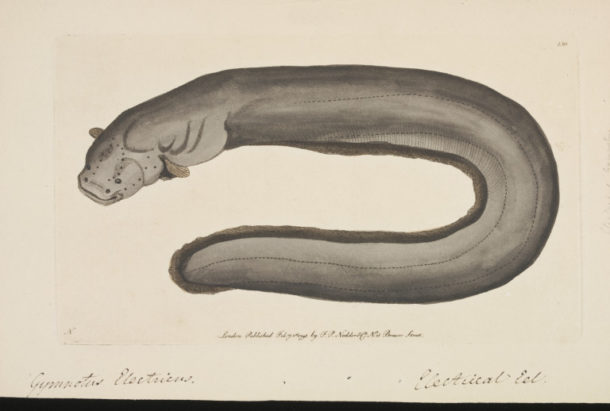

Erotic Electric Eels

Electric eels were first displayed as a scientific phenomenon by Mr George Baker in August 1776. Visitors could pay 2 shillings to watch, 6 pence for a shock or 5 shillings for a spark.

Rumours soon spread that the performances taking place in Baker’s darkened apartment were in fact being used to titillate the middle and upper classes. The eel was used as a penile metaphor, and the shocking sensory experience was eroticised. The eel became a popular subject in printed erotica, as shown by the 1777 poem, The Torpedo, a poem to the Electrical Eel:

To Piccadilly strait she flies,

The Electric eel her want supplies[…]

Sudden his length erected stands,

And gives the electric stroke.

The London Menageries and Chunee the Elephant

Menageries were a significant leisure space in eighteenth and nineteenth century London. Popular amongst the scientifically curious middle and upper classes, menageries fiercely competed to display the ‘newest’, ‘rarest’, and ‘largest’ animals. Exhibits included rhinoceros, lions, and elephants, as well as scientific wonders such as mermaids and shrunken heads.

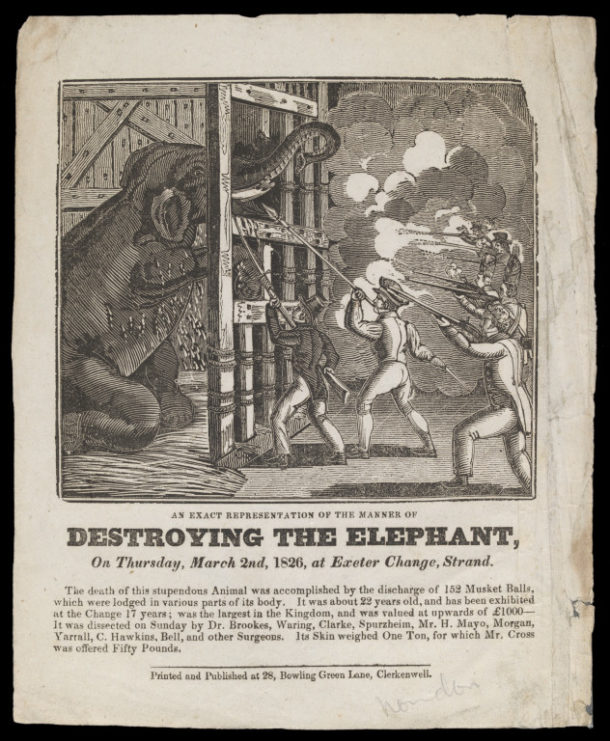

Animals represented a serious investment for proprietors, however species often struggled to adapt to their new climate and enclosed living conditions. Chunee the elephant at the Exeter Exchange menagerie soon outgrew his small cage, and was shot by armed soldiers after becoming restless.

Death did not prevent the Exeter Exchange from profiting from Chunee. The elephant’s body was flayed and dissected, hanging from the front of the Exeter Exchange; his skin was sent to Greenwich for tanning; his rump was cooked as steak; his skeleton was re-assembled and displayed again in the same cage. This was not the end of Chunee’s tragic life, his skeleton ended its days on display in the Hunterian Museum, before eventually being bombed in the Blitz.

Isaac Van Amburgh and Queen Victoria

It was not only animals that became enduring figures in popular culture, owners and trainers also developed reputations for their bravery, mastery, or perceived trickery.

Isaac Van Amburgh was celebrated as the first modern big cat tamer, and the first person to put his head inside a lion’s mouth (and live). Van Amburgh’s performances in London were a resounding success, and he performed on the patented dramatic stage at Drury Lane, earning a reported £300 per week. Queen Victoria watched Van Amburgh perform six times in three months, having his portrait painted and describing her ‘favourite exhibition of the lions’ in her diary.

To find out more about objects relating to animal entertainments visit Search the Collections.