by Carien van Aubel, Conservation Science intern, University of Amsterdam

Collections with objects dating from the late-nineteenth-century onwards often include a variety of plastics. As there are numerous different types of plastics it would be hoped that specific identification would be stated in the records but it is not easy for those not experienced with plastics to identify them. For unambiguous identification it is necessary to carry out technical analysis, mostly time-consuming, costly and not always accessible for every collection. Plastics that are easy to identify often already show degradation signs, like a specific smell, crazing or discolouration. By knowing the nature of materials in a collection, better care can be taken of objects.

The Museum of Design in Plastics (MoDiP) at the Arts University Bournemouth (AUB) developed a flowchart to identify plastics for curators and others with little knowledge of plastic materials.1 It was written in collaboration with experts from academia, industry and museums. Many of the contributors to the MoDiP identification were experts from the Plastics Historical Society (PHS) with an industrial background. Conservators and curators sometimes had difficulties identifying plastics using this resource, possibly because the properties of plastics identified by industry professionals are not completely relevant to the plastic objects in collections. The aim of this project is to identify any weak points in the flowchart when looking at a museum collection and to improve this scheme.

Identification of more than 200 plastic objects from the handling collection in the Conservation Science laboratory was attempted using the flowchart developed by MoDiP. In addition to the identification with this chart, a list of questions a conservator would ask when looking at a plastic object was created. The first three questions are focused on the smell, specific characteristics and if there is a brand name or sign present.2,3 The purpose of starting with these questions is that plastics that are easiest to identify are also immediately identified. The outcome of both methods (MoDiP and questions) was verified by analysis of the plastic with Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy.

After analysis the objects were placed in groups of the same plastics. By looking at the characteristics of the objects in each group some similarities could be found. Every step of identification was recorded, which helped trace back where possible misidentifications were made. It was not easy to identify all plastics. Some objects did not show any style to date them, or there were no production signs visible. Also some definitions in the MoDiP scheme were not clear, e.g. when is an object translucent or flexible?

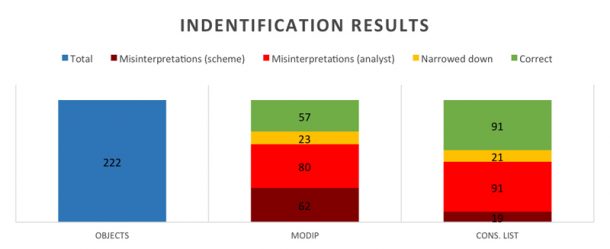

The identification of plastics by the list of questions in the MoDiP flowchart resulted in quicker identification when a plastic had specific characteristics. When this was not the case, it was sometimes impossible to present a list of possibilities. Misidentifications were divided into those made due to weaknesses in the scheme and those made by incorrect interpretation of characteristics of a plastic. When the flowchart resulted in a group of less than four plastics, including the correct one, the identification result is categorised as being ‘narrowed down’ (Figure 1).

More than half of the objects were incorrectly identified with both methods. The list of questions resulted in more correct identifications of plastics. However, misidentification using the MoDiP flowchart was often a result of errors in the charts or because the specific plastic was not included in the scheme. For example, poly vinyl chloride (PVC) is not considered to be transparent or translucent.

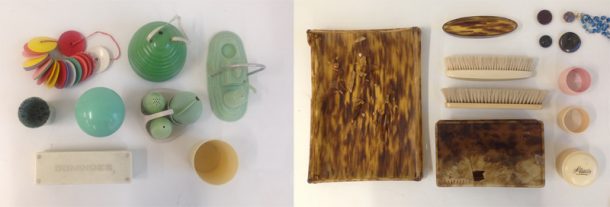

When examining the groups of objects made of the same material, some specific characteristics became more obvious. For example objects made of melamine formaldehyde were often quite colourful, felt cold, hard and often showed an orange peel texture on the surface. Objects from cellulose nitrate were often pale in colour, smelled like camphor or showed the specific cubical crazing when degrading (Figure 2).

The methods and results were discussed with Colin Williamson, specialist in the manufacturing and development of early plastics and a founding member of the PHS. He emphasized the importance of the date of production (the style of an object) and signs of manufacturing processes (Figure 3). Coming from the industry, he also approaches an object by asking: ‘What material would they make it from; what was cheap and easy to use?’ For conservators not specialised in plastics this requires unfamiliar knowledge in plastic manufacturing techniques.

During this project strong and weak points of the MoDiP flowchart could be defined. Plastics with very specific characteristics or ones that already showed degradation were very easy to identify (Figure 4). With the list of questions it was mainly the combination of characteristics that helped in the identification. Even when a specific characteristic of a plastic could immediately be identified, other identification marks helped make a more secure identification. With these outcomes, misidentification in the MoDiP scheme can be adjusted and missing plastics can be added. The advantage of a flowchart for conservators that are not familiar with plastics is that it gives a good and clear overview of the different questions and characteristics.

Now that the basis of information and questions for identification has been developed, a suitable package will be developed to enable conservators to approach the identification of plastics with more confidence, focussing on what is essential to know while not being overwhelmed with unnecessary information. For the V&A collections this will mainly focus on plastics used in fashion and furniture.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to Brenda Keneghan for her guidance during my placement, Bhavesh Shah for instructions using the FTIR spectrometer and Colin Williamson for his help and advice on plastics identification.

References

- MoDiP, A curator’s guide to plastics; A-Z of plastics materials: http://www.modip.ac.uk/resources/curators_guide/A-Z_plastics

- Waentig, Frederike, Plastics in Art, Petersberg: Michael Imhof Verlag GmbH & Co. KG, 2008.

- Quye, Anita; Williamson, Colin; Plastics; collecting and conserving, Edinburgh: NMS Publishing Limited, 1999.

Very interesting i never thought about plastic conservation there’s always something to learn

I had no idea the Victoria and Albert had a plastic conservation department or that lasers are used for cleaning them. Interesting article!

This was an interesting article! I had no idea the Victoria and Albert had a plastic conservation department or that lasers are used for cleaning them. Thank you.

Very much useful and enlightening article!

Thanks a lot for sharing