Richard Rogers was fond of quoting the ancient Athenian oath: ‘I shall leave this City not less but more beautiful than I found it’, which he claimed was the driving ambition behind all his work. The hi-tech architect died on the 18th of December, aged 88, and could be certain that he’d done more than his bit. Lord Rogers, who dressed as if marked out from the crowd with highlighter pen, was a public intellectual who beamed generosity, and was a firm believer in architecture as a vehicle for social and environmental change.

He was most famous for the Pompidou Centre (1971 – 77), that turned architecture into a kind of écorché figure, with the building’s guts and bones exposed to create an exciting, visceral façade. It transformed the elite museum into an accessible fun palace and made Rogers’ reputation as an iconoclast. The multi-towered Lloyds building (1978 – 86) was London’s steampunk, stainless steel version of his trademark inside-out ‘bowellism’. With the Leadenhall Building or Cheesegrater (2010 – 13), three times the size of Lloyds and directly opposite, Rogers left his signature on the city’s skyline.

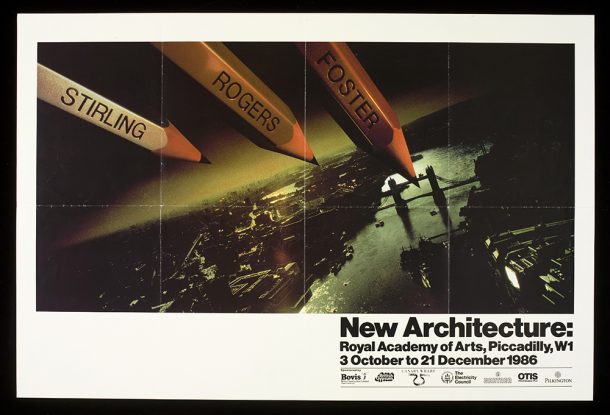

Though his practice Rogers, Stirk, Harbour + Partners built all around the world, London, the city to which he emigrated from Italy in 1939, was the beneficiary of much of Rogers’ visionary thinking. In 1986, having been invited to contribute to the exhibition New Architecture: Foster, Rogers, Stirling at the Royal Academy, Rogers chose to submit designs for ‘London as it could be’. The plan resembles a science-fiction utopia in which spiky towers sprout from new islands, modelled on North Sea oil rigs, afloat on the River Thames. It placed him at the head of the movement for reform in London, and the accompanying book, A New London (written with Mark Fisher MP), was essentially the Labour Party environment manifesto for the 1992 election.

In 1995, Rogers became the first architect to deliver the Reith Lectures. He painted a bleak picture of London as an insatiable and polluting Gargantua, “one of the least sustainable cities in Europe”. In one year it got through 100 supertankers of oil, 1.2 million tons of timber, 1.2 million tons of metal, and 1 billion tons of water. And it produced 15 million tons of rubbish, 7.5 million tons of sewage and 60 million tons of carbon monoxide. Although the city covered only 400,000 acres and contained only 12 per cent of the UK’s population, it required 50 million acres, all around the world, to sate its appetite.

Against this monstrous backdrop, Rogers outlined his plans for ‘a humanist city’: building work, guided by strategic master plans, would transform the polluted centre; congestion taxes would reduce traffic; public transport would be free; people would use new cycle routes and squares would be pedestrianised; avenues would be lined with trees and the Thames would become ‘London’s necklace’, fronted by new gardens and crossed by new bridges, with his Millennium Dome in Greenwich as the necklace’s ‘clasp’.

A born persuader, with considerable charm and infectious optimism, Rogers was keen to follow aspiration with legislation. As a Labour peer and chair of the Urban Task Force, and then as Ken Livingstone’s mayoral advisor, Rogers pushed his vision of an urban renaissance. He argued for the development of brownfield sites and high-density living, intended to foster social cohesion and encourage the middle classes back into the ‘compact city’ to protect the countryside from suburbs and satellites.

These ideas have been the model of urban regeneration for the last two decades and have served to redefine London and other British cities, making them more sophisticated and European. “Successful urban regeneration,” he said, “is design led. Promoting sustainable lifestyles and social inclusion in our towns and cities depends on the design of the physical environment”. Critics, fearing for existing communities, dubbed it ‘pacification by cappuccino’ and noted how his firm designed luxury developments such as One Hyde Park, investment opportunities that resembled HSBC hard drives and little reflected his community ambitions.

Rogers converted two adjoining townhouses in Chelsea to create his own house, with a huge, triple-height space, nicknamed ‘the piazza’, where he and his wife, Ruth (founder of the River Café), hosted legendary parties, including an annual celebration of the Serpentine pavilion. He was a bon vivant, and also a great supporter of new talent, never reluctant to put his head above the parapet in defence of the environmental causes or campaigns for social justice in which he believed. Rogers retired from architecture only last year, and was a once in a generation voice, who transformed London as much as did Christopher Wren.

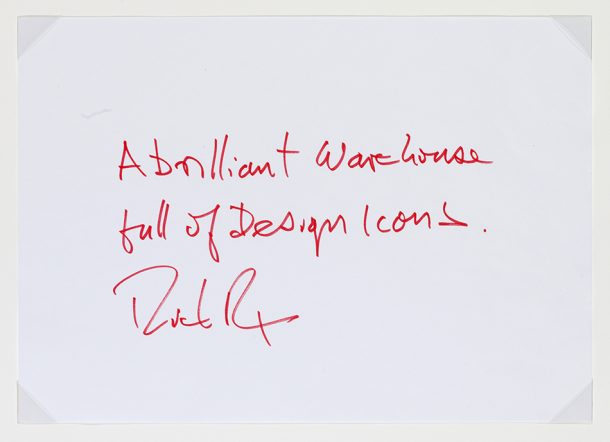

Lord Rogers spoke to Christopher Turner at the V&A in September 2018 to discuss and debate his five ideas about how best to address the crisis of availability and affordability of housing in London.