History may be written by the victors, but the History of Design is written by the victors with the most stuff. Since we’re dependent on material sources– drawings, textiles, furniture, metalwork, ceramics, you name it– the way we remember what happened in the past and the value we attach to it all comes down to the physical availability of these things. By definition museums understand this process and seek to preserve objects. But museums aren’t neutral absorbers of stuff—what we have depends on what is acquired from year to year. It depends on who has the foresight to think not only about what is interesting now, but what may be or should be useful to historians in the future. This is why the V&A collects everything from Renaissance bronzes to e-cigarettes.

Some artists and designers have an eye to posterity and make careful provisions for their archives. The legacy of others is down to public appreciation, sheer chance, or the loyalty of friends and family.

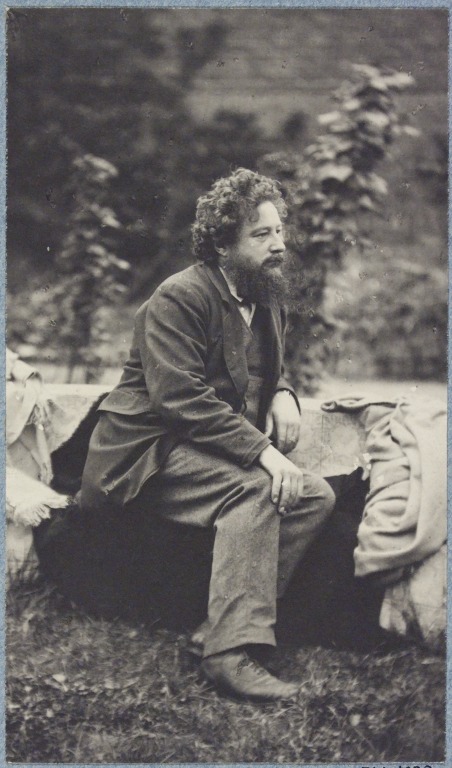

You will probably recognise this endearingly coiffured social reformer and designer as William Morris. Today, as in the 1870s, Morris is a household name. His wallpaper and textile designs are so popular and well-known that is hard to image this not being the case. However, as this interesting exhibition at Standen shows, the enduring appeal of Morris’s designs was not guaranteed.

William Morris’s lasting significance as a designer is in part thanks to the careful management of his legacy by his younger daughter, Mary ‘May’ Morris. Renowned in her own right as a talented designer and embroiderer, May maintained a long relationship with the V&A, lending objects to numerous exhibitions. May was committed to spreading the philosophy and design ideals of the Arts and Crafts movement. In addition to lending objects for display, she lectured widely and published instruction manuals for embroidery which insisted on the necessity of good design.

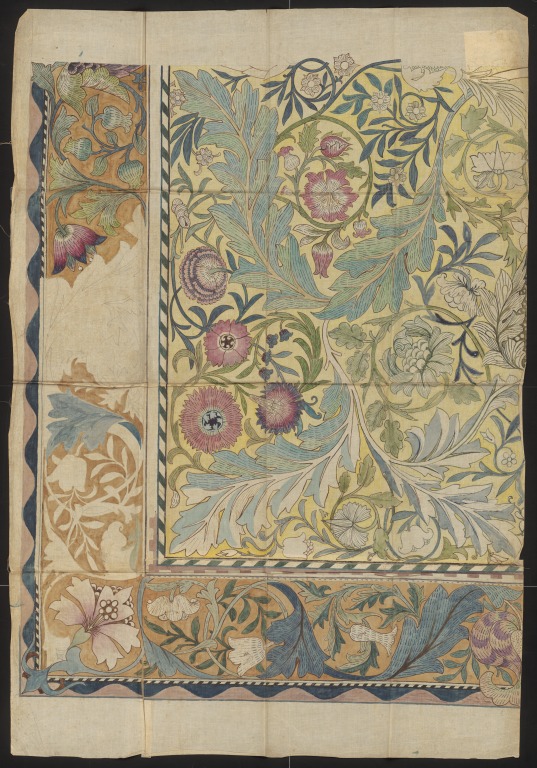

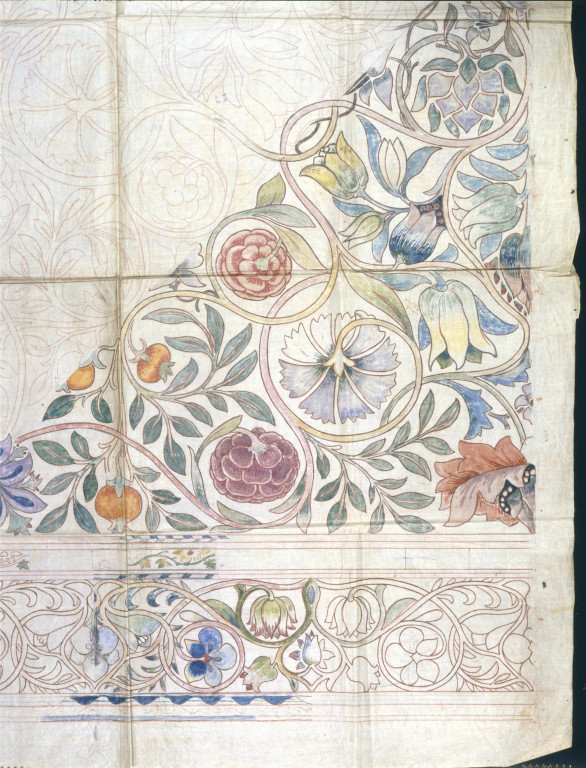

Upon her death in 1938 May bequeathed to the V&A, alongside textiles, ceramics, glass, jewellery and furniture, thirty designs for wallpaper, textiles and embroidery. These beautiful ‘working’ drawings demonstrate William Morris’s design process. As May described: “If you will look through a number of his designs for chintzes and papers, you will see that he thought in mass, as it were, not in line…”

We are only able to “look through a number of his designs”– that is, the actual working drawings in which Morris communicated his thoughts– thanks to May. While the Museum has collected individual pieces by Morris since 1939, the majority of our designs come from the original bequest.

Throughout her life, May Morris balanced her own artistic career with faithful commitment to her father’s work and legacy. Included amongst her bequest to the V&A are some designs created by May herself, testament to her own important role within the Arts and Crafts movement.

The V&A still welcomes Legacies to enhance its collections and support its work. We run regular events, including curator-led talks about Legacies that have helped shaped the Museum’s collection. For further information please click here, or contact Susan Hughes, Legacies Manager on +44 (0)20 7942 2716 or email: legacy@vam.ac.uk

Dear Sir or Madam

I am trying to find out details and circumstances of the commissioning by Serguei Schukin of the tapestry “The adoration of the Magi” in 1902.

Are there any archives that I can consult?

Thank you for any help

Best regards

Corinne Lejeune