There is a moment – beyond the point when George Floyd stopped asking to stand up, beyond the stage when he ceased pleading for a breath, beyond that heart-chilling moment when he called for his mother – there is a point when George’s body lets go – gives in to a chilling still silence.

But the knee on the neck persists.

The politics of that silence has a long history for peoples of African descent.

Imposed silence has played a significant part in a long history of racism, as a key element in the centuries-long project of suppression and infantilization of Black people.

Silence, so often enforced by the knee or the boot, so often backed up by legislation and weaponry, so often justified with bad science or corrupt systems of justice. The rendering of a people, a culture mute, opposition impossible, agency broken, supplicant, void.

Sometimes silence was imposed, as when debate was banned and cultural expression was outlawed and even musical instruments were confiscated or destroyed – and sometimes a very selective deafness was deployed to help salve colonial consciences. At its worst, blankets were thrown over African colonies to extinguish protest, hide legitimate opposition and assuage colonial guilt. And creativity was often dampened, education often tightly controlled, and artistic expression was suppressed.

When in the eighteenth century the most respected European intellectuals sought to justify the burgeoning expansion of European interests in Africa, it was posited as a programme of shining a light into the African vacuum. They saw the consolidation of European engagement in Africa in part as a search for cultures that were like theirs – they wanted to find buildings, material culture, artistic conventions and intellectual achievements that were similar or comparable to the accomplishments of cultures of Europe. They sought what Immanuel Kant described as ‘architectonic’ bodies of knowledge, complex cultural superstructures with their own intellectual provenance. They looked for writing traditions like those that underpinned classical European cultures – and yet, as Kant and many other intellectuals of the Enlightenment wrote, they simply could not find them. These men who defined the Enlightenment, constructed its hierarchies and categories, these intellectuals who laid out the framework of modern law, morality and its identified metaphysics – looked upon Africa, a well-populated and varied-cultured continent, and saw in its peoples nothing – a void, a cultural tabula rasa – silence. It made colonialism, and the imposition of Western cultural norms, seem like a kindness.

And that is what is so powerful about this work by Yinka Shonibare.

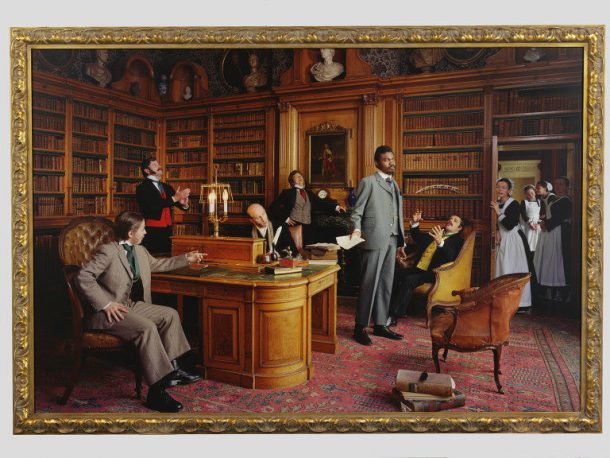

Inspired by the paintings of Hogarth, it is a work that tells a story of an African Dandy: confident, dapper, handsome – holding forth amongst the elite at the very height of Empire. The women swoon, the men hold their breath admiringly – waiting on his words. He holds in his hand a sheaf of papers – an agenda, a thesis, a plan. He commands the floor about to break the silence, gazing out toward new horizons, undaunted by the platform.

The Enlightenment is the period in which the museum sector was born and alongside it was the intellectual apparatus of race and racism. What Shonibare seeks to do here is to challenge that implicit hierarchy and to do so explicitly.

We must do the same.

Diary of a Victorian Dandy: 14.00 hours (Photograph)

Bravo V&A for speaking out so clearly. I hope you use your incredible resources to put on a #blacklivesmatter exhibition. A free exhibition. With amazing educational links. School trips for every school! Your posts since this terrible murder have given me hope. Please don’t let the silence continue…

Powerfully expressed – and a great choice of artwork. You also give me hope for the space and effort to promote BAME voices and histories in the V&A East development.

Where are my comments that a museum cannotatthe same time hold looted maqdala artefacts and proclaim solidarity wth the African peoples?

Kwame Opoku.