Introduction

In terms of gender identity and masculine expression, the eighteenth century was an important time of transition. While in 1700, there was a certain amount of tolerance for effeminacy, and for bisexuality, by 1800 the understanding of what it meant to be a man was considerably more rigid, closely policed, and what we might call ‘heteronormative’ – treating heterosexual desire, and the presentation of that desire, as the default mode of being. What I want to show you here is a selection of objects in our collection which represent the changing attitude towards male sexuality throughout the eighteenth century, taking a roughly chronological view of the most important shifts and themes. Using these objects as a starting point, I’m going to give you an overview of how male homosexuality, effeminacy and so-called sexual deviancy were practiced and perceived in this period. In this first blog post, we’ll look broadly at male sexuality in the context of popular culture, particularly fashion and the theatre. This will be followed by a second post which looks more closely at the relationship between homoeroticism, fine art and connoisseurship in the eighteenth century.

The Macaroni and his ancestors

The notable thing about homosexuality in the 18th century was the fact that it shifted from an action to an identity. The act of sodomy, on which homosexuality was predicated, changed from something one did, to something one was – i.e., a ‘sodomite’. Homosexuality had been acceptable, even fashionable, in ancient Greece and Rome, and Platonic homoeroticism was tolerated during the Renaissance period, especially in Italy. However, the concept of gay orientation did not develop during this time. Engaging in erotic exchanges with other men, whether physical or ideal, did not ‘make’ a man a homosexual to the exclusion of all other identities.

By the eighteenth century, we can still see some remnants of the earlier tolerance and fluidity, particularly among the elite. The British courtier John Hervey was openly bisexual, and is thought to have had indiscreet affairs with the Earl of Ilchester and Frederick, Prince of Wales. Though his dalliances prompted some satirical poetry, he never seriously faced punishment or social exclusion based upon his sexuality. In law, however, sexual relations between men remained illegal. The act of sodomy, also known as buggery, was in theory punishable by death. In practice, the more likely charge was ‘assault with sodomitical intent’, which would be punished by a spell in the pillory to bring shame upon the convicted men. Nonetheless, there was a cautious gay subculture in eighteenth-century London, which centred around a number of taverns known as molly houses. In addition to functioning as meeting places for gay or bisexual men, they were also the home of a discreet drag culture, a space for men to dress and present themselves as women.

How were these men perceived? The online records of the Old Bailey are one of the best resources for reconstructing gay culture in this period, precisely because its expression was illegal and therefore likely to end up in court records. It’s worth noting that, in the accounts of police raids on London molly houses, the men arrested were from a variety of social backgrounds. Often they were tradesmen, artisans and apprentices – certainly not members of the fashionable elite. In mainstream popular culture, however, the figure of the effeminate, overdressed elite man was the stereotype most commonly associated with homosexuality. In the worlds of music, the theatre and visual culture, gayness permeated numerous characters of this type without being explicitly alluded to.

Let’s look at two objects which illustrate this idea: a ceramic figure, and a print. The ceramic figure, produced around 1750 by the Bow porcelain factory in London, is a portrait of the actor Henry Woodward. Woodward is shown in the costume of one of his most celebrated characters, ‘The Fine Gentleman’ from David Garrick’s 1740 play Lethe. The Fine Gentleman, like so many comic theatrical characters between about 1680 and 1770, is supposed to be an overdressed man of fashion, which in the context of the period implies that he is effeminate. The character is not explicitly written as gay, which would have been unthinkable in this period, but is clearly lacking in heterosexual masculine prowess – one scene alludes to his propensity to run away when approached by a pretty woman, while in another he talks at length of the eunuchs and dancing masters he collected around himself while on the Grand Tour of Europe. His oversized hat and elaborate waistcoat are exaggerated for comic effect, but they also suggest an unmanly interest in adornment and vanity. Paradoxically, like so many of the clothes and accessories worn by so-called fops or beaux, this exaggeration also takes on a phallic and virile aspect, especially as the figure is posed with the front of his waistcoat held suggestively upwards and outwards..

Similarly, the print – which was designed by the comic painter William Hogarth in 1746, and is titled Taste in High Life – focuses on the figure of a fashionable, effeminate gentleman in order to make its point; playing around with the suggestion of homosexuality without ever directly referencing it. The gentleman, on the right, is again dressed in an exaggerated style; the feminine nature of his slender physique and beribboned clothing juxtaposed with the phallic symbolism of his hair and cane. In conversing with a woman who, while equally overdressed is shown as old and ugly, it’s suggested that his only interest in women is for conversation and fashionable society, not for sex. Hogarth, who was well-known for his sophisticated visual codes, has given the viewer a clue into this man’s sexual identity through his accessories. He holds a fur muff – pun definitely intended – in front of his crotch, which suggests that his true gender ought to be female – but at the same time, his hand penetrates the muff, suggesting heterosexual interest. Under his arm, he holds a large black tricorned hat, the shape of which also resembles the female pudenda – so much so, in fact, that the phrase ‘old hat’ was common slang for female genitals. So Hogarth is hinting at a fluid identity here, rather than a straightforward binary of male and female, or straight and gay.

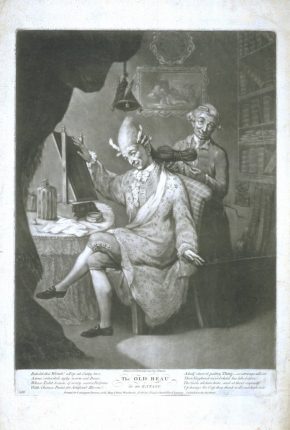

Both this figure, and Garrick’s Fine Gentleman, were progenitors of a social stereotype known as the Macaroni. The Macaronies represented an extreme form of male fashion in the 1770s; their name derived from the Macaroni Club, a group of elite young men who had travelled extensively and were mad for all things foreign (themselves named after the pasta dish). This passion for foreign culture extended to an outlandish mode of dress: high, powdered wigs topped with miniscule hats, face powder and rouge, long swords, elaborate lace ruffles and tight, colourful silk suits – again, projecting an unexpectedly phallic virility. The Macaroni became a comic shorthand for ‘fashion victim’ status in popular prints, ballads and on ceramics, such as this earthenware tea canister, where the high hair and tiny hat of the Macaroni man is amusingly juxtaposed with his plump figure. This fashionable comedy was laced with suggestions of effeminacy and, sometimes, homoeroticism. In this print, The Old Beau in an Extasy, for example, the elderly Macaroni sits at a dressing table in a flowered robe and curling papers – a setting normally associated with female portraiture – seemingly admiring the handiwork of his male hairdresser. This ‘extasy’, however, could and would have been read as an emotion with erotic overtones, the Macaroni being aroused both by his own adorned appearance, and by the man who attends him in this intimate setting – particularly as the extreme shapes of his hair (or wig) are again producing phallic images. (Ironically, many of the actual Macaronis, such as the young MP Charles James Fox, were known for their numerous heterosexual affairs).

As we’ve seen, the representation of homosexuality in popular culture was coded rather than open, implied by behaviours such as the way one dressed, stood or spoke, because the actual act of sodomy as defined in law was considered too taboo even to mention by name. The one thing that virtually all of these representations had in common, however, was their elite nature, connecting wealth, fashion and foreign travel and culture with the idea of gayness. In the following post, we will look at how elite men, particularly those who collected art and antiquities, were influenced in the 18th century by the homoeroticism of the classical world.

Some further reading

Jody Greene, ‘Public Secrets: Sodomy and the Pillory in the Eighteenth Century and Beyond’ in The Eighteenth Century, vol. 44 (2003), pp.203-32.

Amelia Rauser, ‘Hair, Authenticity and the Self-Made Macaroni’, in Eighteenth-Century Studies, vol.38 (2004), pp.101-17

Randolph Trumbach, Sex and the Gender Revolution, Volume 1: Heterosexuality and the Third Gender in Enlightenment London (Chicago, 1998).

The abominable church made whatever word they could think or to mean sex. Deviant was made to be sex. Carnal was made to be sex. Fornication was made to be sex. The church concocted the name Sodomy to mean sex. Gays, zoosexuals pedophilia people transvestites were called perverts. A perverted, froward, vexing tongue, wags at them.

Church leaders are deviant. Church leaders have a carnal mind. Church leaders are born of fornication, being like Christs enemies.

God’s law is not legal and illegal. Jesus did not teach leagal and illegal.

Sodomites were against gays, wanting to be a judge.

Court records is immitating God’s book, judging the living and the dead.

The abominable church made whatever word they could think or to mean sex. Deviant was made to be sex. Carnal was made to be sex. Fornication was made to be sex. The church concocted the name Sodomy to mean sex. Gays, zoosexuals pedophilia people transvestites were called perverts. A perverted, froward, vexing tongue, wags at them.

Church leaders are deviant. Church leaders have a carnal mind. Church leaders are born of fornication, being like Christs enemies.

God’s law is not legal and illegal. Jesus did not teach leagal and illegal.

Sodomites were against gays, wanting to be a judge.

Court records are immitating God’s book, judging the living and the dead.