The public buildings scattered around South Kensington offer great examples of the use of terra cotta as a building material in 19th century Britain. In a series of posts linked to my work on the history of the Royal Albert Hall I have been exploring different aspects of this trend. In today’s post I will look into the fame architectural terracotta acquired through its presentation at international exhibitions, in particular that of 1867. Moreover, I will be discussing a building presented on that occasion by the British. While replicating a Hindoo temple, it simultaneously demonstrated British proficiency in terracotta production and mastery of cutting-edge steam technology.

The Great Exhibition of 1851 and ‘the value of baked clay’

In the early 19th century Britain rediscovered terracotta as a building material. This led to a very considerable growth in the quantity and variety of architectural ceramic produced. Industrial exhibitions reflected this. As the renowned manufacturer John Marriott Blashfield noted in 1855,

[The Great Exhibition of 1851] called public notice to the value of baked clay, materials for architectural and garden decoration

Subsequent international fairs strengthened this trend. By the late 1860es the use of terracotta in architecture had increased Europe wide. Henry Cole gave a good overview of this in his ‘Report on terra-cotta’ from the Paris Exhibition of 1867.

Henry Cole’s ‘Report on terra-cotta’ from the Paris Exhibition of 1867

In his report Cole listed terra cotta exhibits on show from a number of countries. He commented on their strengths, weaknesses and future potentials. France’s exhibits impressed him. In particular Cole thought the objects produced by Messrs. Virebent’s firm to be ‘highly suggestive to architects for all styles’. Their principal exhibit ‘was in the shape of a triangular chapel, of an hybrid byzantine character, showing al the varieties of their various processes’.

Similarly, Prussian terra cotta attracted Cole’s praise. Especially noteworthy were its excellent material qualities. Thus, It was ‘hard, compact, well baked’. However, its aesthetic merits were less remarkable: ‘according to German taste, is monotonous in colour’.

Interestingly, many of the objects he described featured within the ‘Machinery group’. This confirms that, in the context of the international exhibition, the main interest for terracotta was in its potential as a material for ‘artistic’ industrial production as well as for use in utilitarian buildings.

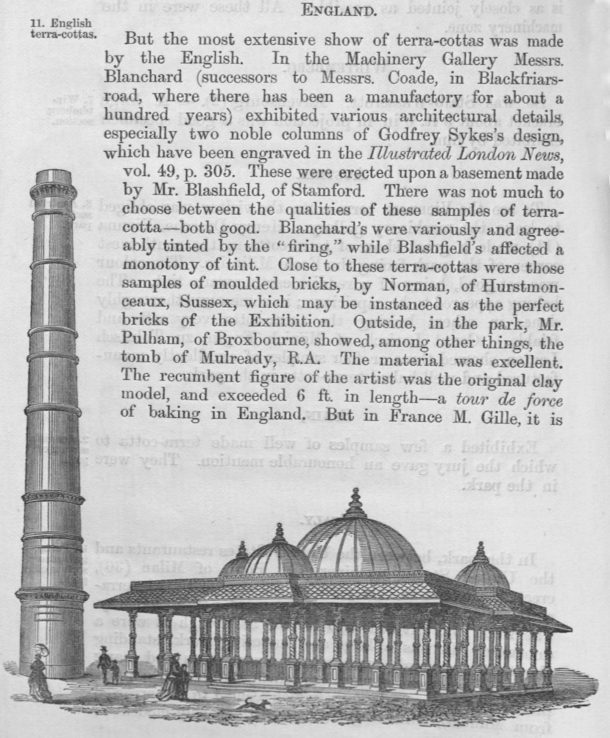

Moreover, Cole in his -not necessarily unbiased- report underlined that “the most extensive show of terra cotta was made by the English”. He also noted with pride the utilitarian, practical and jet artistic use to which the English put terracotta at the exhibition.

British terracotta and steam power at the 1867 exhibition

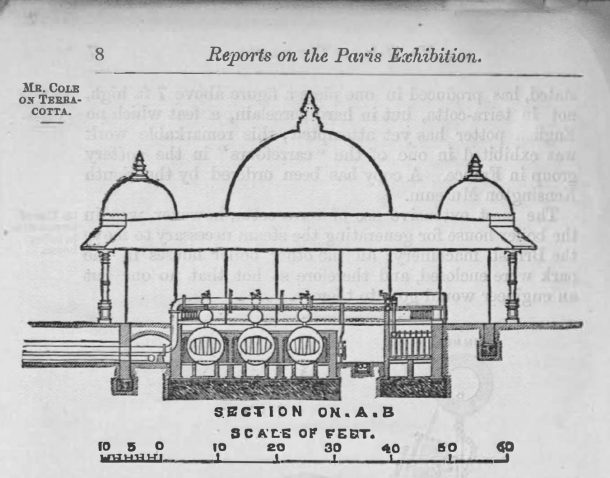

The main British artefact Cole described in his report is a partially open boiler house. The design ensured rich natural ventilation. Thanks to this feature, the temperature inside the boiler house did not rise excessively, despite the presence of powerful steam engines. The public could therefore conveniently inspect the machines (fig. 1).

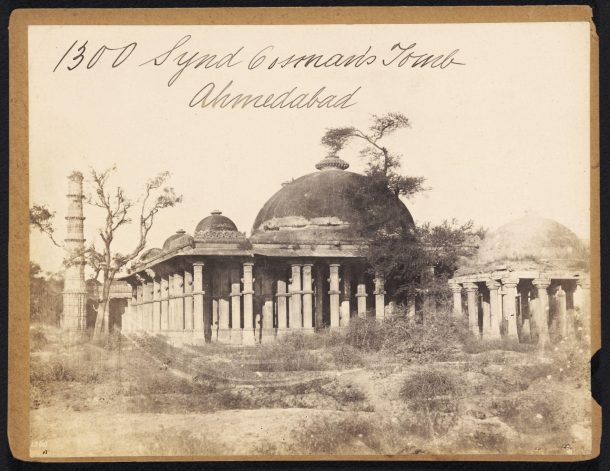

According to Cole, the building was ‘designed after Syud Cosman’s tomb of the fifteenth century at Ahmedabad’ (fig. 2). This complex became well-known in 19th century Britain thanks to photographs. Ahmedabad was an important manufacturing and trading centre. Thus, many objects in this period came into the South Kensington collections from this city.

‘Italian terra-cotta and not Hindoo details’

However, the similarities between the British boiler House and the original Hindoo architecture were only related to the general arrangement. Notably Cole, in his report remarks that, for the boiler house

‘Italian terra-cotta and not Hindoo details were used for the sake of economy, in order that they might be employed hereafter in England’

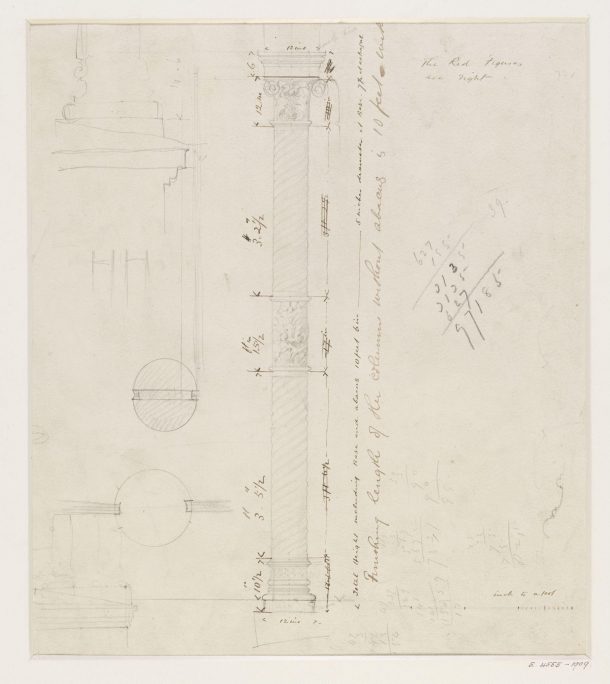

Indeed, the columns of the pavilion resemble very closely those adorning the South Kensington’s Horticultural Gardens, going back to the early 1860s (fig. 3).

In these years Godfrey Sykes was experimenting with terracotta as an architectural material in connection with different buildings in South Kensington. For instance he designed similar twisted columns for the façade of the South Kensington Museum – today’s V&A (fig. 4).

Experiments with this material continued also after Sykes’ sudden death in February 1866. Indeed, his pupil Reuben Townroe took over the task of designing terracotta decorations. He did this, for example, for the Royal Albert Hall’s façade (fig. 5).

The playfulness and freedom with which designers used terracotta and moulded bricks at the 1867 exhibition are representative of the direction in which architectural terracotta was moving. A material with a long history and illustrious ‘pedigree’ ‘conquered’ the 19th century and was used extensively in architecture. Thus, we find it in buildings of different styles and ambition: from monumental architecture, like the Royal Albert Hall and the Natural History Museum, to middleclass dwellings up and down the country.

If you would like to know more

This post is an outcome of the Project Designing the Future: Innovation and the Construction of the Royal Albert Hall, funded by the Leverhulme Trust. Read the full story of the Albert Hall’s construction in the forthcoming monograph The Royal Albert Hall: Building the Arts and Sciences.

To learn more more about the unique characteristics and background of the Royal Albert Hall head to the other posts connected to this project.