Lorraine Kypiotis is a lecturer in Art History and Theory at National Art School in Sydney

To view the remnants of the facial features of Michelangelo’s David at the National Art School in Sydney is somewhat like considering the curious pieces of flotsam and jetsam washed ashore after a tropical storm. They are, in so many ways, castaways adrift on an island continent.

As for David himself – he may also have washed ashore sometime in the past but, alas, we have no record of this: he has gone missing – perhaps wandered off into the bush, as so many of our early settlers, never to be seen again. But how did his eyes, ears, nose and lips find their way to NAS?

In the late 19th century, at a time when the cultural influence of classical learning was still strong, NAS, purchased plaster casts from the London formatore, Brucciani, also the cast maker for the V&A.

From a collection once numbering in the hundreds however, only about 30 complete casts have survived. Amongst them are the features of David’s face.

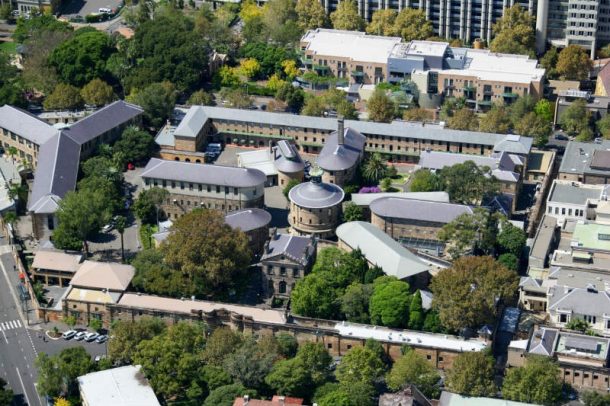

The National Art School, has a history extending back almost 175 years, to the first lecture presented at the Sydney Mechanics’ School of Arts in 1843, in a move to provide technical education to the young men and women of the colony. After much growth, it eventually found its permanent home in the old Darlinghurst Goal in 1922.

A contemporary newspaper reported the transformation from “House of Correction to School”, with the repurposing of cell-blocks into studios:

“Where there were formerly silence and tears are now the hum and joy of learning. Classes in art.…are now in progress….”

Unfortunately not long after – as was the case with many collections globally – academic attitudes regarding their significance changed, eventually turning to complete disparagement by the mid-20th century. It was during this period that many casts disappeared or were destroyed.

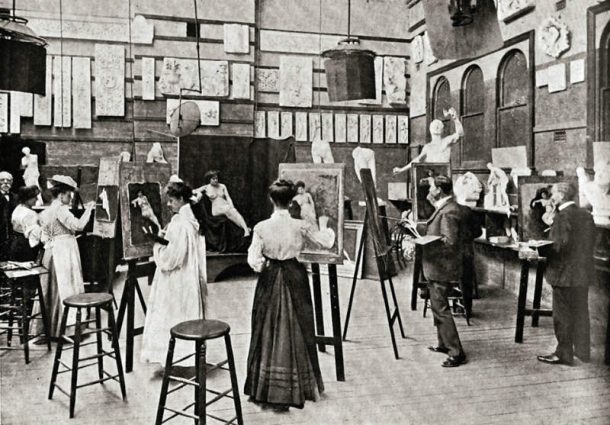

In the 19th century, however, they were considered ‘essential’ for art education. Drawing classes were offered from around 1843 but the Art School did not begin to purchase casts until the 1880s and within a decade amassed quite a substantial collection: well over 500 casts (and moulds) with stock numbers corresponding to those in Brucciani’s Catalogues.

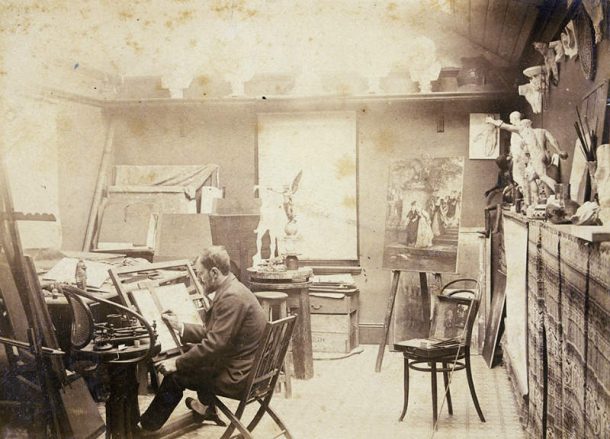

Who was responsible for the purchase of the casts? The first Head of Art appointed in 1883 was Lucien Henry, a Frenchman and graduate of the École de Beaux Arts. He quite likely chose casts representative of his own education and that mirrored the tastes of the British system in which he was employed.

There have been suggestions that the casts were his personal property, however, Henry’s circumstances before he arrived in Sydney were such that they precluded him from bringing anything as cumbersome as casts with him from France. He was a Communard who had been sentenced to a term of punishment in Noumea in 1873, arriving in Sydney only after having been granted amnesty by the French Government. He would have had very little in his possession.

I am sure that the irony has not escaped you, that the first head of art in a country originally populated by prisoners, and of an art school that would eventually find home in a gaol, was a convict. Also ironic, given that it was a society founded on a penal system, was the fear across the eastern seaboard of Australia of ‘an influx of certain foreign criminals into NSW’. Despite these fears, Lucien Henry established himself as a painter within six months.

Employed by the Board of Education, he ordered a stock of classical casts. He advised that students follow a strict program of drawing and only after they began “to show a firmness in… drawing” from the cast could they progress to the proportion and construction of the figure and life drawing. Then “when the student shows a very decided temperament for figure…Houdon’s écorché and Mich.angelo are to be drawn at almost every angle. Michel Angelo’s four reclining figures….from the modelling room may follow.”

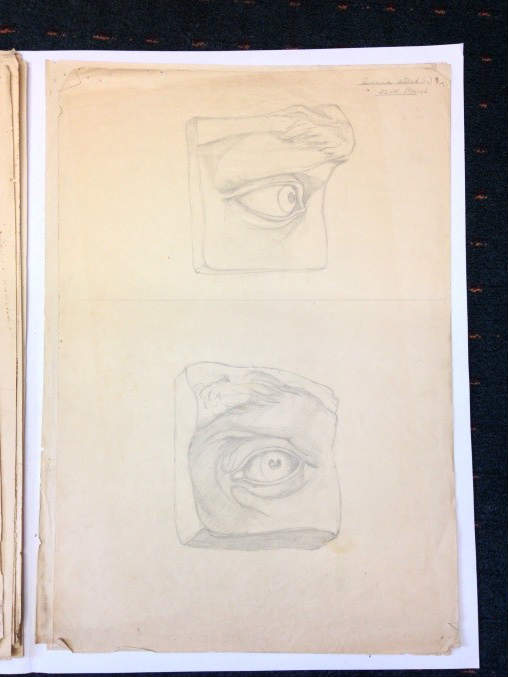

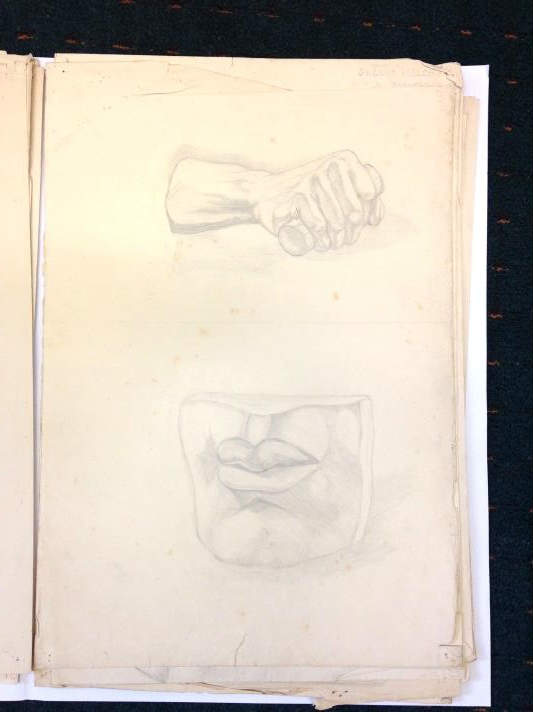

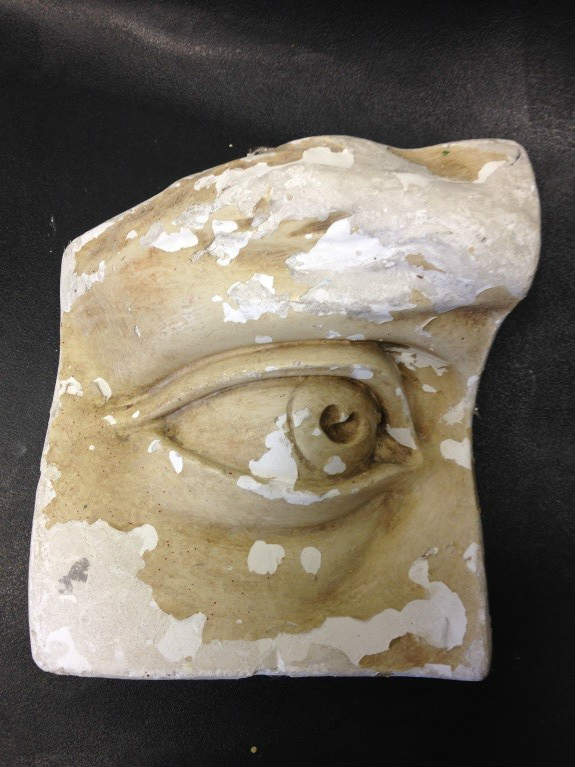

Michelangelo’s four reclining figures are of course the allegorical figures from the Medici tombs in Florence. NAS was also in possession of the eyes, ears, mouth and nose of Michelangelo’s David, in both anatomical and faceted reproduction. Certainly by the early 20th century, as NAS was a “working art school” with a plaster room, moulds of these features could be re-produced.

The School thus had “on hand” the following moulds: 2 of the eyes of David: right and left; 11 of the nose, lips, ears and mouth; a mould of the mouth and nose together as well as of the eye and nose together. Unfortunately, NAS has only 1 mould left: David’s right eye.

During these early years, whilst some technical colleges in Australia purchased directly from Brucciani, the wealth of the NAS collection was such that they became a local supplier of casts and moulds.

A newspaper report of 1912 mentions that a delivery to Gordon College, north of Sydney, included:

“….casts from moulds taken from Michel Angelo’s famous statue of David …. utilised throughout the world as models of the best type for anatomical studies.” These were of course the details of David’s facial features.”

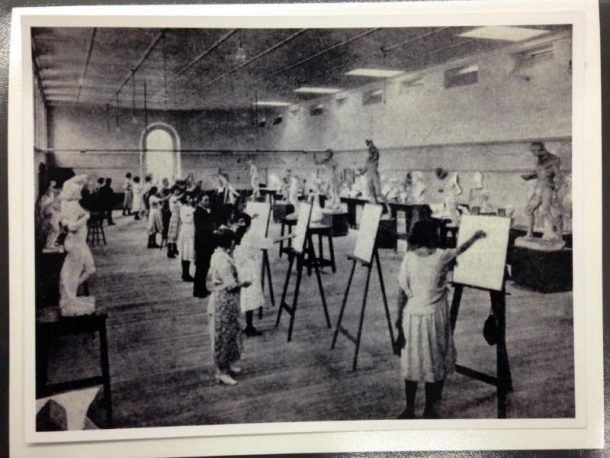

The curricula which implemented the use of these plaster casts had also grown solidly through the decades: the 1909 handbook lists among its courses “Painting and modelling from the Antique” and “Modelling and Casting”. It emphasises both the importance of drawing practice in an artist’s training and how much time was spent on casts: “Drawing from the Antique is a most important study and closely associated with that of life….In the first year the student is kept fully occupied in drawing and shading from the head, bust, feet, hands, and other details of the figure…in the second year the full figure engages their attention.”

Certainly throughout the 20th century drawing from the casts continued as a core subject and David’s features were still an important part of an artist’s training.

It is heartening that after decades of denigration these casts are being used once again in classes – especially in Sculpture and Drawing. The 1st year Sculpture students engage in a program centred on the human figure and once again make use of both Houdon’s écorché figures and Michelangelo: in the absence of David, the Dying Slave is their model as are the features of David’s face.

In Drawing also, they use both anatomical and faceted casts of David’s features in order to gain an understanding of structure, tone and three dimensional form. Beyond this aspect, the casts offer the possibility of generating more interesting and dynamic imagery when used in a more conceptual manner.

As I have mentioned, only around 30 or so of Brucciani’s complete originals still survive – but these are experiencing a resurgence and once again are used by students: in class and as part of contemporary practice. Sometimes navigating the nuances of reclaimed cultural patrimony does not mean new ground but instead returning to old ground and old objects in new ways. The castaways are in the process of being rescued.

——————————

Lorraine Kypiotis

Lorraine Kypiotis is a lecturer in Art History and Theory at the National Art School in Sydney. She has a MA in Italian Renaissance Studies (U Syd) and is currently engaged in a Phd at the University of Sydney focussing on the history and contemporary use of the cast collection of the National Art School. It is entitled “Castaways”. Lorraine also frequently guest lectures at the Art Gallery of NSW and has recently recorded a series of interviews with ABC Radio’s Nightlife program on art historical topics.

I regularly visit your site and find a lot of interesting information. Not only good posts but also great comments. Thank you and look forward to your page growing stronger.