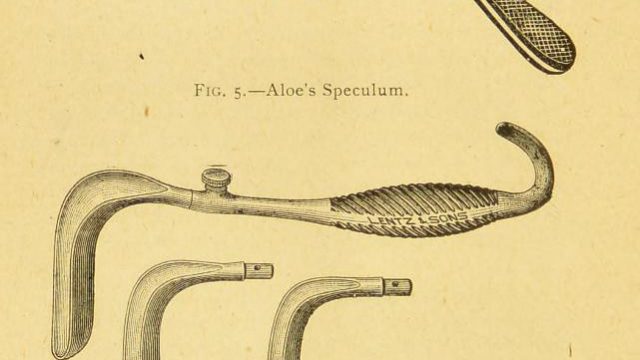

The speculum is an object designed to reveal the vagina and cervix to a doctor or nurse. But the history of the speculum exposes much more than that; it sheds light on inequality and the different ways power is unevenly distributed.

Through working on the ‘Content/Data/Object: Open-Source Speculum Project’ at the V&A, I have learnt a little of the history of this object. The speculum was developed by the notorious gynaecologist J. Marion Simms, who experimented on enslaved women without anaesthetic (only three of whose names have survived in the historical record: Anarcha, Betsey, Lucy). As fellow contributor and design historian, Lisa Godson has explored, the speculum was also used as a tool for state-sponsored gynaecological violence in Britain in the 1860s, policing sex-workers who were thought to have syphilis and subjecting them to invasive internal examinations, even though syphilis could not always be seen by looking through the speculum. The sex workers, rather than their clients, were seen as the repository of disease and a threat to national health.

As fellow contributor on this project, feminist and anti-racism activist Isma Benboulerbah has observed, the speculum remains an object that is not fit for purpose for a wide range of people. This includes those who have experienced female genital mutilation, trans people, survivors of sexual violence and those who require their hymen to remain intact.

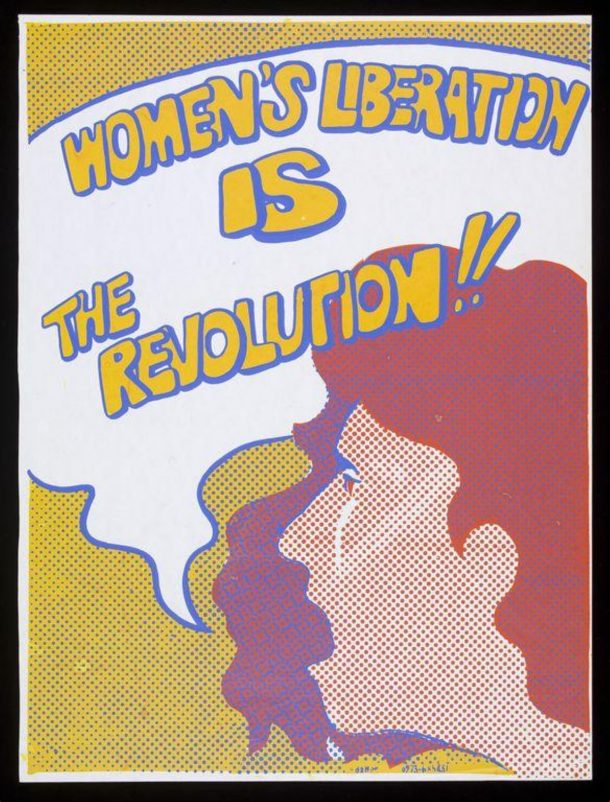

Given the history of the speculum and its ongoing use, I wondered why in the late 1960s and early 1970s, ‘second wave‘ feminists tried to reclaim this tool? Small groups would gather and carry out a ‘self-exam’. As the New Zealand feminist periodical Broadsheet explained, a ‘self-exam is carried out with the aid of a torch, mirror and plastic speculum, and with support from other women in the group’. Through this method, women’s cervices and vaginas were revealed to their owners. The process aimed to empower women with knowledge about their genitals and revoke the shame and alienation many felt about their bodies.

Placing the feminist practice of the self-exam into dialogue with the history of design reveals that feminists sought to transcend the affordance of the speculum. ‘Affordance’ is a term used by people who study design to describe how an object’s use is built into its design. When you use an object and it feels natural or intuitive, you are likely running into the object’s affordance. But imagination can transcend affordance. When children play, they often transcend the affordance or the intended use of everyday objects. In play, a rope can become a snake, a skipping rope or a strand of spaghetti.

The expansive imagination of feminists transcended the affordance of the speculum. For feminists, the speculum seemed to epitomise how medicine, which was supposed to heal, could often harm. Doctors held the expertise and information about women’s bodies and women were kept ignorant. Those involved in women’s liberation recognised that the tool’s affordance– the apparently ‘natural’ way to use it – also reflected a power relation. The speculum’s design requires two people to use it; the first, the patient, lies back with their knees bent, and the other, a medical professional, places the duckbill inside and opens it up. The patient’s cervix and vagina are revealed to the person looking, but the patient remains in the dark. Feminists sought to transcend the affordance of the speculum through self-exam, and employed an everyday object, the hand mirror, to do so. Jan McKenley, a UK feminist who founded Hackney Black Women’s Consciousness Raising Group and was one of the coordinators of the National Abortion Campaign, recalled a self-exam on a women’s health retreat where she lay in the arms of another woman for support, while a different woman held a hand mirror. To McKenley, this ‘epitomi[zed] the best of women’s liberation because I looked at my vagina and it was beautiful … feminism gave me my body back … and it was magic.’

As well as the power dynamic between doctor and patient, efficiency was, and still is, embedded in the affordance of the speculum. The plastic speculum pictured below boasts a ‘multi-thread screw for easier/fast opening and closing.’ The speculum’s affordance speaks to a broader context of health where efficiency is valued over patient care. On the NHS for example, doctors appointments are now 10 minutes. Many doctors as well as patients have been vocal about the constraints of this. They have highlighted the stress on doctors and patients alike and the increased likelihood of mistakes being made when doctors run late, or are fatigued.

The feminist health movement challenged this efficiency – women took their time and explored their bodies, inside as out, often with the support of other women. This feminist sense of slowing down was carried across the health movement in inspiring and empowering ways. In an oral history interview, I spoke with Australian feminist Gabrielle Hewison about her experience of working in abortion provision. She revealed that feminist and non-feminist abortion provisions were like ‘chalk and cheese.’ One of the major differences that Hewison drew out was that in feminist services ‘you took your time. The counselling could be as long as was needed [for the individual] … It wasn’t a conveyor belt.’ Lynnley McGrath, an advocate for feminist health services said something similar about services for women in Perth, Australia. Here, women were not obliged to leave immediately after an appointment and this slowing down could be truly transformative: ‘I remember one day a woman coming in … She was there all day. Sometimes she cried, sometimes she talked, sometimes she slept, sometimes she had a cup of tea … At the end of the day she said “this has changed my life”.’

Yet there were certainly many women who did not participate in self-examinations; those who did not have time or felt that self-examinations were self-indulgent, those who did not feel welcome in a majority white women’s movement, or those who had other political priorities. As historian Theresa Barnes discusses, when women involved in the Zimbabwean liberation struggle came to New York in 1979, the North American women’s health movement invited them to take part in a pelvic exam using a speculum. They were largely ambivalent about this and felt amid the fast-paced Chimurenga (Liberation War) that they had more important things to do and could not slow down. Joyce Kangai, one of the representatives, noted that sexual health and reproductive justice was important, but ‘not until Zimbabwe is free can we stop to think about it’.

It from this history of feminist self-help, of slowing down, but also from an understanding that feminism has historically been marked by exclusion that GynePunk’s 3D Printed Speculum emerges. This object takes the spirit of the women’s liberation movement – which sought to empower women collectively- and includes those such as sex workers and migrant communities, who have historically experienced exclusion, including from feminism. GynePunk also combines cutting-edge technology such as 3D printing with the spirit of slowing down and combines this new tech with ‘herbs and natural knowledges’. While Gyne Punk’s 3D speculum is not perfect, it is an example of what becomes possible when healing is placed before efficiency and when healthcare is developed by those who need it. In the words of Gynepunk: ‘Ahora las brujas tenemos las llamas’ (‘the witches now have the flames’).