Object Pitch Day 7 began with a high-speed intro from Bill Sherman – by this point we were well drilled in what was going to happen – as we settled down for a packed programme of five pitches that stretched right back to the ancient world and dealt with object types including furniture, embroidery and even human remains…

OP7/01

We started with a very literary pitch from Beverley Hart, Librarian in the Theatre & Performance Department, who demonstrated the many layers of meaning that can be accrued by a single object type, one that she presented as a “universal shorthand” for our inevitable demise.

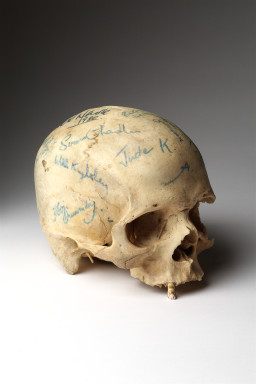

Revealing her object, which she’d brought with her, we were asked to, ‘Meet Yorick: Jonathan Price’s co-star in the Royal Court ‘Hamlet’ in 1980’.

Beverley explained that ‘Yorick’ is one of two prop skulls in the Theatre & Performance collection, as ‘two heads are better than one’. (The other example was a gift from the writer Victor Hugo to legendary actress Sarah Bernhardt after she played Hamlet.)

Beverley’s choice of skull was, in fact, the rather grizzly top prize in a raffle – as signed by the cast of the 1980 production – with ‘the winner so spooked by scooping the prize that they passed it onto the V&A’. We were amused to learn that cranium (it has no mandible) also appears to have ‘lost teeth during the run’ – something that can be confirmed by scrutinising production photos. That we don’t know very much more about the skull ‘underlines death’s anonymity’.

Beverley went onto elaborate the numerous associations of this object type in literature, art and design, and beyond. Appropriately, this tour began with the character Yorick from Shakespeare’s Hamlet –a “practical joker, professional jester, princely playmate and subject of the most famous misquotation of all time” – with the skull arguably becoming a signifier of the play itself.

Moving beyond Shakespeare, she told us that skulls were fashionable Jacobean stage props, appearing in ‘The Revenger’s Tragedy’ and ‘The White Devil’, where “a ghost carries a pot of lilies containing a skull”.

This dramatic incident was used as a stepping-stone to evoke numerous, often interlinked allusions to skulls in art, literature and history. From T. S. Elliot’s ‘Whispers of Immortality’ where ‘Webster was much possessed by death / And saw the skull beneath the skin’, through P. D. James’s crime novel, ‘The Skull Beneath the Skin’, set amidst a production of the Duchess of Malfi, to Joseph Conrad’s ‘Heart of Darkness’ and “Mr Kurtz’s compound lined with human skulls”, a sight Beverley adeptly linked to Khmer Rouge victims in Cambodia.

Beverley continued to dazzle us by referencing Poet Laureate Carol Ann Duffy’s ‘Small Female Skull’, the poet A. E. Housman, tombstone doggerel (“As you are now, so once was I / As I am now, you too shall be”) and the philosopher Walter Benjamin’s remark that, “Everything about history that, from the very beginning, has been untimely, sorrowful, unsuccessful, is expressed as a face—or rather in a death’s head”.

Pausing for breath, she drew these citations together to argue for the “many worlds latent in her object”, as “what constitutes more universal shorthand for our common humanity and mortality bereft of creed, colour, gender, sexuality than this seat of reason and memory?”

Gathering pace again, she identified this impulse in ‘the skeletal leader in the eerie conga of the Danse Macabre”, the ‘memento mori’ (trans. ‘remember [that you have] to die’) in paintings, hiding in “anamorphic form in Holbein’s double portrait ‘The Ambassadors’” and, even less subtly, in Damien Hirst’s flashy diamond-encrusted platinum ‘For the Love of God’.

In the world beyond, Beverley spotted skulls everywhere, suggesting their universality and flexibility as a symbol of mourning, mortality, warning and even vitality. From the visual shorthand on mourning objects, especially jewellery, and at the feet of the dead child Lydia Dwight in a touching object in the V&A’s collection…

…to the place of skulls as fashion and cult items from “gothic to goth regalia to Hell’s Angels’ gear”, and from the traditional pirate to a symbol “beloved of the health and safety industry denoting danger”.

Skulls are there in Golgotha or Mount Calvary, the site of Jesus’s crucifixion, “meaning the place of the skull”, and as an essential part of the aesthetic of other spaces associated with death, like charnel houses and catacombs. They were “venerated by Celts, appear on the death’s head hawk moth”, are the focus of “trepanning, archaeology, pathology and Victorian phrenology”, and denoted the “SS-Totenkopfverbände – the Death’s-Head Units – that controlled the Nazi death camps”.

As Beverley also explained, they are embedded in language: in synonyms (“the noodle, the noddle, the pate, the poll, the brainpan”) and as colloquial expressions (“You can be numbskull or out of your skull”).

In concluding, she made of her pitch an elegant momento mori: “Remembering our legal duty to respect human remains, I’ll end where I began – with Hamlet – ‘That skull had a tongue in and could sing once’.”

OP7/02

Lucy Trench, Head of Interpretation, began her pitch by asking, “I hope I’m not breaking the rules by doing the history of an object backwards?” Starting at the end, Blythe House in February 2014, she told us about how her object, The Endymion Cabinet, was filmed for a gallery interactive for the Europe 1600-1800 Galleries.

The cabinet’s first sighting in the museum is assured by a photograph from the guardbooks, one of the 900 volumes of photographs of V&A objects in situ in the Museum between 1853 and 1996, where it was shown in the north cloisters in 1883. Beyond this, the date of its acquisition (1856), the price paid to an anonymous seller (£132) and the hunch it “might have been displayed in Marlborough House” during the 19th century, “we know almost nothing about it”.

In place of ‘hard’ facts, Lucy developed her pitch around a very early modern notion – that of microcosm meaning ‘small world’ – noting that “to recreate a history for this object is as much an act of the imagination as it is scholarship”

We do know that the Endymion Cabinet was one of “ca. 60 cabinets all made in Paris between 1630 and 1650”. It was “connected to the idea of a cabinet – as a collection, as a room and as a piece of furniture that itself houses collections”.

Lucy drew our attention to the “most interesting thing about the V&A cabinet”: its lavish decoration. It is covered “with carved scenes adapted from a novel titled ‘Endymion’ that was published in Paris in 1624” and written by the French poet and novelist Jean Ogier de Gombauld. We don’t know very much about Ogier de Gombauld. He appears to have been a Huguenot (a French Protestant) and was very close to Marie de Medici and Anne of Austria, the mother and wife of the French King, Louis XIII, as well as being “connected to feminine literary circles in Paris, being particularly attached to Madame de Rambouillet, who had one of the first salons in Paris”.

Lucy accompanied her biography of the author by showing contemporary paintings of his possible patronesses, remarking “you’ll notice they’re all wearing black”, which she described as the “the colour of the 17th century”.

In this “century of war, plague and death”, Lucy also noted the other connotations of black as a marker of status – “an extremely prestigious colour because it was very difficult to dye” – “a good black was one of the most expensive colours you could wear”.

It matters, then, that black is the colour of the outside of the Endymion Cabinet. As Lucy noted, her object offers many more clues as to how and what it meant: “as you start peeling them away, you see lots of other references to 17th century ideas”.

The engraved tulip decoration recalls “the flower paintings produced at the time that were intended to convey the ideas of mortality or vanitas”, as outlined in Beverley’s pitch. Less morbid is the presence of ripple moulding on the cabinet; as Lucy explained, showing a printed diagram of a ripple-moulding plane from a work of 1630, this “was the latest technology in creating decoration”. Moreover, the mirrored glass, probably made in Murano and visible once the cabinet is opened, produces a “wonderful prospect and relates to very fashionable ideas of optics”.

The cabinet’s materials also suggest something about its origins. Partly decorated by means of the marquetry technique, using coloured bone and ivory, Lucy speculated: “it’s possible the ivory was traded from Africa to Antwerp or Dieppe”.

The cabinet’s exterior is in the hardwood ebony and we were enchanted when Lucy showed us less visible parts and the signs of the “hand of the worker present on the slightly rougher woodwork on the back’”. That Ebony, as a rare wood taking between 100 and 300 years to mature, is extremely hard and difficult to work, further attests to the skill of the maker.

Pushing beyond the environs of the workshop, Lucy then took us to “forests in Mauritius, Madagascar and Réunion” where the ebony used to make the cabinet might have grown. Following this trail to its logical conclusion, she remarked that this final destination ultimately takes us “back to tortoises – as ebony trees were proliferated through the forest by giant tortoises who eat the seeds and pass them!”

To gales of laughter she signed off, “Like endless debates about where life begins: does the life of this cabinet begin in Paris in the 1630s or does it begin with a tortoise’s lunch?”

OP7/03

Next up was Roisin Inglesby, Assistant Curator of Designs, who pitched an ‘orphan object’ “found in the Furniture Conservation studio with no number, no references, no acquisition record whatsoever”. What followed was an impressive unpacking of what this object was and, more importantly, what it meant for the people who made and owned it.

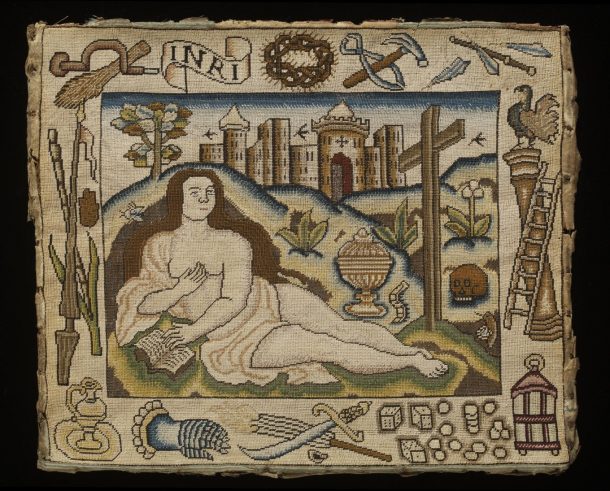

Adopting the simplest object categorisation, it is an example of “17th century English embroidery – according to people who know about these things – attached to a later piece of silk, as evidenced by the nail marks visible on its outer edges”.

Speculating on how her embroidery ended up at the V&A, Roisin told us it “was probably brought here at some stage in the last 150 years –possibly to be released from the frame it was in – perhaps the frame was the valuable bit?” but never reclaimed (“perhaps the owner died”) and there are no records of it before 2011. Unsurprisingly for such an old embroidery, “the colours on back are much brighter, suggesting lots of light exposure during its life”.

Roisin then complicated and enhanced her object by working through an impressive diagram that set the embroidery right in the middle of – not quite 100 worlds but certainly getting there.

Modestly framing her pitch as a “lazy way to recruit 100 research assistants to help me with this project”, she went through the many ways you might think about an ‘orphan’ embroidery.

These included the physicality of the object – its small size, that it was executed in “fairly simple tent stitch with no fancy raised work”. This must be contrasted with the unusualness of its subject matter: the embroidery “looks completely different from any other piece anybody knows about: in V&A and elsewhere no one has ever seen anything like it”.

The embroidery also prompts us to take a closer look at the silk trade and, indeed, “James I’s attempt to encourage cultivation of domestic silk industry by having mulberry trees planted in the garden of what is now Buckingham Palace”, as well as the ways in which design ideas circulated in the early modern world in printed sources and in the imagination of makers.

Significantly, “17th-century English embroidery tends to be done to fairly standard lines, with women and young girls working to approved themes, such as heroic and virtuous women”. Roisin told us that there was a “set stock of seven or eight images with 20 or 30 others that you get occasionally”. These included “Old Testament stories about virtuous or heroic women, like Bathsheba, Judith and Susannah”.

By contrast, Roisin’s object is the only known embroidery to show Mary Magdalene – “and it is undoubtedly her with the long hair, the urn, the instruments of the passion and the book, all classic Magdalene iconography”.

Understanding why the V&A’s embroidery is the only one of its type, Roisin proposed three, potentially overlapping, questions: “Is it because the object’s subject matter was taken from the New Testament? Is it a case of survival – were many more made? Or did the maker make something truly unique?”

Roisin also noted that “Mary Magdalene had an interesting post-Reformation history”, which helps destabilise the meanings associated with her embroidery. “Is this a religious object? Is it for the home? Is it a Catholic object in a Protestant world? What does it do in the domestic sphere?” Comparative objects help push this point, with Roisin showing us this painting of Louise de Kérouaille, Duchess of Portsmouth, Charles II’s mistress in the 1670s and 80s, where she was provocatively depicted as Mary Magdalene.

Concluding with a barrage of questions, Roisin amply demonstrated the many more lines of enquiry her object supports: “Where does it fit into the histories of embroidery and design? Does it fit within art history? Or not? Does that matter? Is this only part of women’s history? Is that too limiting?” And, finishing on one of the fundamental questions posed by anyone engaged in object-focused research: “Is an anonymous object an opportunity? Or is it impossible to interpret?”

OP7/04

Our next brave pitcher, Sacha Than, who works in the Directorate, took us back to the ancient world with her choice: the plaster cast of Trajan’s Column, currently located in two bits in the museum’s Cast Courts and the largest object in the V&A at 39m (125 ft).

This choice was underpinned by the ways in which the object “transcends worlds – the ancient and modern – spheres of academia and tourism – originality and manufacturing”.

To understand the cast of Trajan’s Column, we were taken on “a whistle-stop tour of Classical world” starting with the Emperor Trajan . Sacha told us that the beginning of his reign came “after a tumultuous period of seven emperors ruling in quick succession with some reigning only for two or three months”.

This instability and upheaval can be contrasted with Trajan’s historical reputation as the second of the so-called Five Good Emperors. This term, coined by the Florentine diplomat and political theorist Machiavelli, was later popularised by the English historian Edward Gibbon in the 18th century; historical distance that “gives a good sense of Trajan’s enduring popularity over the centuries”.

What more do we know about the man behind the column? He “wasn’t born an heir to the Roman throne – he wasn’t even from an aristocratic background”. Instead, as Sacha explained, he was born in Baetica, a Roman province of Spain, the son of a provincial governor.

The product of a “military-political environment, Trajan followed his father’s lead by first becoming a commander in the army”, and then holding political office. Like his father, he was the beneficiary of imperial patronage, with the Emperor Domitian “advancing his career by granting him the prestigious office of consulship, only two were granted in Rome each year”.

Domitian was assassinated in a palace conspiracy “and replaced by first of Five Good Emperors, Nerva, who died of old age soon after but not before nominating Trajan as his successor”. Trajan’s accession was popular with the power bases of the senate and the army, and was followed by “successful reign of 19 years”.

As Sacha explained, the building programme undertaken during his reign dramatically “reshaped the city of Rome, including the construction of Trajan’s column, a landmark in city from 113 AD – the year of its dedication”.

The column’s spiral relief is in two parts, with “the bottom half showing the First Dacian War and the second half, the Second Dacian War”. These were “major military conflicts between Rome and an area covered by modern-day Moldova, Romania, Bulgaria, Hungary, Ukraine and Serbia, which concluded with Roman victory”. In fact, as Sacha told us, the “building programme was actually funded with spoils from the Dacian Wars”.

The details in the decorative reliefs are “a hugely important source for understanding Roman military culture, with over 2500 figures of soldiers, sailors, the emperor and priests, amongst others, providing a wealth of knowledge”.

In concluding her pitch, Sacha brought us from the spoils of Roman warfare to the V&A’s Cast Courts where, she proposed, the V&A’s copy is actually “better than original”! Backing up this controversial opinion, she argued that the museum’s version is “better preserved and more accessible, as it’s not surrounded by traffic, like the one in Rome”.

When it first arrived at the V&A in 1864, “foreign travel not as widely available as it is now, which made the cast of Trojan’s Column, as a world landmark, accessible to people who would never have been able to see original”.

Take that Rome!

OP7/05

Object Pitch Day 7 was wrapped up by Susan North, Curator of 17th and 18th Century Fashion, who interrogated the task at hand.

She started by asking: “Do we choose an object that is actually two objects, such as the jacket that belonged to Margaret Layton and which she is shown wearing in a contemporary painting…?”

“…or an object in lots of different parts, like the Oxburgh Hangings?”

“Do we choose something in lots of different media, as in Lord and Lady Clapham…?

“Or a very simple object, like a pin?”

Having whetted our appetite, she astonished the room by rejecting the process, stating, “In all honesty can I come up with 100 worlds? 15 or 20 at the most. Can I say my object is better than anyone else’s? No I can’t!”

Noting that “an inability to follow instructions appeared on every report card I ever received”, she then went on to propose her own spin on a history of an OBJECT in 100 worlds: “100 Worlds of Inspiration”.

This would see “anybody, just everybody” get in on the selection process: from visitors, artists, designers, craftspeople, makers, professional and amateurs (“the people in our stores and study rooms learning something from our collections”), to historians, teachers, re-enactors, students, doctors, scientists, mathematicians and even the obligatory smattering of ‘celebs’.

Arguing that “probably every single word the V&A produces is created by some curator rabbiting on about why something is important”, Susan reiterated the aims of an OBJECT in 100 worlds by advocating the inclusion of voices from beyond the V&A’s curatorial departments: “the cleaners, warders, object handlers, conservators, all of whom spend as much time – if not more – with the objects as curators do”.

Susan developed her definition of inspiration, telling us that it encompasses the translation of design ideas across historical periods (“how a 16th-century Italian silk studied by William Morris inspired his design for wallpaper”), between media (“from the visual to musical”), but also allows for personal and emotional experiences attached to the V&A (“the marriage proposal in the garden, finding out you got accepted by Central Saint Martins in the V&A café”).

As she acknowledged, pursuing the trickily intangible issue of inspiration is not without its challenges. After all, it means “putting the script in someone else’s hands and asking people to describe non-verbal processes”.

Susan concluded Object Pitch Day 7 on an upbeat note, as she convinced us that the pros of the process definitely outweigh the cons, as a way of being “collective and inclusive, and bringing together collections, staff and, most importantly the visitor, who are not the passive recipients of what we think is important but, instead, the stars of the show, to make something that is forward-looking”.

And, with her final words – “that every single object in V&A is the embodiment of a fantastic story and a catalyst for future art and design for centuries to come” – she got to the heart of what the project – and the museum – is all about.

***

Our penultimate Pitch Day certainly left us with a lot to think about. It also gave Bill Sherman the opportunity to accrue all kinds of credit for future museum activities – from extra words in gallery text (from Lucy Trench) and extra bullet points at senior management meetings (from Sacha Than) – as pitchers let excitement about their objects get the better of them, breaking the all-important five-minute rule.

Who can blame them? Once again, we were treated to top-notch object research. Beverley, Lucy and Roisin’s pitches were masterclasses in how to produce rich, convincing analyses about objects where the supporting documentation is scarce, while Sacha presented her choice of the cast of Trajan’s Column as a way of interrogating the original. Finally, in upending the whole process, Susan emphasized the importance of bringing in new and unexpected perspectives on V&A collections: something that is absolutely at the heart of a history of the OBJECT in 100 worlds.

We also learnt that the 17th century is the natural home for those with an unhealthy preoccupation with the colour black, and all things morbid, melancholy and, frankly, a bit goth!

With only one more session to go, we weren’t looking forward to making our final decision…