For religious communities during lockdown, one of the biggest challenges has been the closure of places of worship, and the consequent need to find new ways of staying spiritually connected. In the absence of architecture, household objects have helped bridge that gap. For me, it has been an Orthodox icon.

One of the most uncomfortable memories that I have from my time at university is when a student entered my room in the halls of residence, ridiculed the icon I had above my bed and called me an ‘idol worshiper’. The icon was one of the Annunciation, similar to the Annunciation icon in the V&A’s collection, and it was salvaged by my grandmother when fleeing Smyrna in 1922. It had been in my childhood bedroom for as long as I could remember.

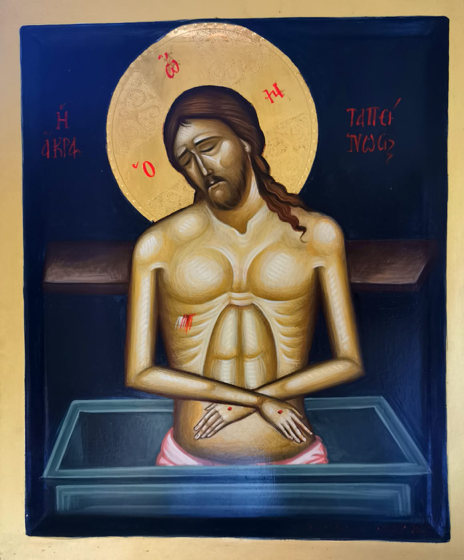

Icons are central motifs in Orthodox Christianity and can be found in churches as well as people’s homes, offices, shops, boats, cars, motorbikes, even bags and purses. Icons are not worshiped as idols but instead are venerated and considered to have the ability to connect Orthodox Christians to the divine.

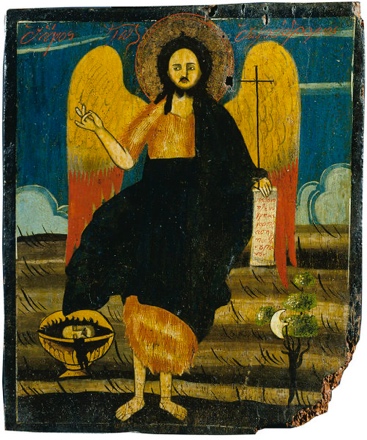

Icons are neither imaginary representations of religious events, nor are they naturalistic. Rather, as the Greek origin of the term icon (eikon) indicates, they are the ‘image’, a holy representation, that goes beyond appearances and towards spiritual essence. Apostle Luke is believed to have created the first icon and since then, iconographers use his motifs to depict, with the blessing of the Church and while praying, what they consider to be the Truth. The student that ridiculed my icon was not unique. In the history of the Byzantine Empire, the veneration of icons was twice disputed and, in both cases, restored. The last restoration of the veneration of icons is still celebrated today as the Feast of Orthodoxy. And there is a relevant icon to mark the event.

Lockdown closed all places of worship while coinciding with significant annual religious events like Passover, Easter and Eid. For the Orthodox Church, Easter is the most momentous event of the year. There are additional services in the months preceding, dramatically increasing the week before Easter Sunday with long daily morning, afternoon and evening services. There are numerous icons to commemorate the Holy events and many special traditions. This year all services were completed behind locked doors and live streamed to the congregations.

After three weeks with no Sunday Mass, I still remember my anticipation and engagement with the first live streaming, which was on Palm Sunday. It was great to be able to follow the service and see our treasured priest conducting it. I took pictures of my screen and sent them to the priest and to my friends – what joy! More services followed. Even though having them was vital, the experience was not the same as being in Church– it simply felt flat. Some attempts to recreate the environment at home, such as burning incense, slightly improved it, but did not replace the experience of being in a place of worship.

The Orthodox spirituality embodied in the space of the church is an assault on the senses. The visual communication of the holy icons and symbols in the building’s decor; the auditory inspiration of the chanting and the rustling of the rich heavy vestments; the sweet scent of the incense burning; the touching of the cross and the taste of bread and wine bridge the natural to the supernatural. Many have reported the presence of God in Orthodox worship, simply because of the heavenly atmosphere of the service.

Church services resumed on the 5th of July. Following all the new rules, including observing social distancing and sharing contact details, altered the experience. The much anticipated return to communal worship, though, still made for an emotionally charged occasion.

I wish further lockdown will not be needed, but if it is, alongside the online services, many Orthodox Christians will find comfort and solace in their icons at home. They will, once again, act as a prompt for personal prayer; strengthen their faith, and remain a symbol of life and hope.

Further Reading:

Icons Study Guide, V&A Website.

Kallistos (Bishop of Diokleia), The Orthodox Church, Penguin Adult, 1993.

‘A Reader’s Guide to Orthodox Icons’, website.

Related Objects from the Collections:

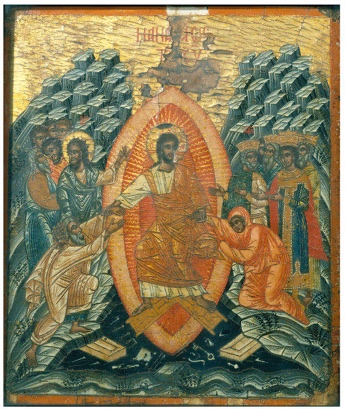

‘The Anastasis [Harrowing of Hell]’, Greece, 18th century (W.6-1927)

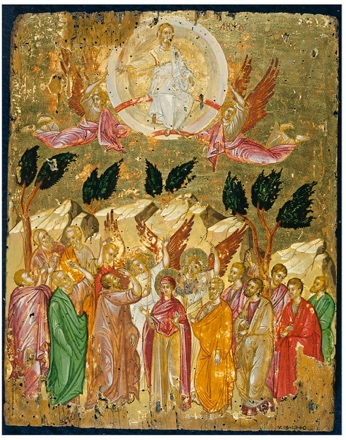

‘The Ascension’, Russia, 15th century (W.15-1940)

‘Triptych with the Mother of God of the Rose and Saints’, Greece, 19th century (W.68-1928)

Censer, Ethiopa, 18th century (62-1870)

Chalice, Moscow, 1702 (LOAN:GILBERT.93-2008)